Municipal modernity: the politics of leisure and Johannesburg's swimming baths, 1920s to 1930s

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 August 2021

Louis Grundlingh

Some often view swimming baths1 simply as functional structures, oblivious that they are historically constructed public social spaces and overlooking what they represent in a community, specifically in suburbs, and what they tell of a city's history.2 However, Van Leeuwen has prompted a scholarly interest in the swimming bath as a distinct and quintessentially modern form of urban space.3 Wiltse4 and Love5 continued Van Leeuwen's pioneering work. Wiltse traced the development of municipal swimming baths to elegant modern recreational spaces while Love's study investigated the competitive and recreational forms of aquatic sport. Recently, Kozma, Teperics and Radics rightfully claimed that ‘researchers have been paying increasing attention to study the connections between sport and urban development’.6 This is confirmed by similar scholars specializing in the history of swimming baths.7 Likewise, using a cultural, municipal and class lens, this article unlocks the establishment, design and usage of swimming baths for Johannesburg's white residents in a rapidly changing urban environment. It thus introduces an ignored piece of the history of Johannesburg's leisure facilities.

Until recently, the implicit acceptance of ‘race’ as the primary category of inquiry meant that most studies of Johannesburg interpreted the city as nothing but ‘the spatial embodiment of unequal economic relations and coercive and segregationist policies’.8 This scholarship is based on a long tradition focusing more on, inter alia, the geographies of poverty and less on the cartographies of affluence.9 Not denying this reality,10 these accounts envisioned the city not as an aesthetic project but as a space of division.

However, Parnell and Mabin were decidedly critical of what they saw as an ‘obsession with race’ in existing South African urban historiography.11 This approach obscured and impoverished an understanding of how modernist planning, a concern for ‘improvement’ as well as municipal power, had shaped South African cities. Recently, Bickford-Smith added that a history of South African cities, not focusing on race alone, is overdue.12 What was needed was a history from the perspective of powerful local politicians and bureaucrats: in this case, the role of the protagonist in Johannesburg's City Council, namely English-speaking, white, male, middle class and elite, shaping the urban fabric. Their crucial relationship with urban place has been neglected in existing historiography despite the fact that Britishness was the ‘prime nationalism of South Africa, against which all subsequent ones…reacted’.13 This article shares this concern and unpacks their role in providing swimming baths to selected areas of the city.

Cities were unmistakably the creation of their middle class, the theatre where this elite ‘sought, extended, expressed and defended its power’.14 For the purpose of this article, the ‘theatre’ was Johannesburg's suburbs.15 In explaining middle-class suburbs, Gunn's insights into ‘the distinction between centre and periphery’16 is as helpful as Beavon's explanation of the development of Johannesburg's suburbs. Beavon demonstrated how physical geography, economic forces and the relationships between space, race and class determined Johannesburg's layout of suburbs on the periphery.17 This crucial point helps to explain the council's decision where and when to build swimming baths, thus adding another important layer to the fabric of suburban facilities. In short, Johannesburg's swimming baths became a distinctly suburban phenomenon, changing suburbanites’ lives.

Studies of the histories of leisure and recreation only make fleeting reference to municipal sports provision.18 McShane and Katzer agree that, although sporting space reflects key shifts in thinking about town planning, sports architecture and physical infrastructure are likewise inadequately examined in the historiography of urban design.19 The corrective is, as Doyle reminds us, to emphasize the history of municipal governance, especially as the council is the agent of change.20

Whilst there is a dearth in the scholarship on this in South Africa, the history of local government and the wielding of political power has attracted heightened interest from urban and administrative historians.21 For example, in England, municipalities were the driving force and the sole provider of swimming baths,22 with the city of Manchester leading the way.23 In Victoria, Australia, the initiative also came from municipalities.24 This article likewise makes a contribution to this under-researched field.

In their reflections on urban development in South Africa, scholars used the prism of modernist planning.25 South African cities became ‘monuments to progress and modernity…equalling any modern counterpart in Europe and North America’. 26 Right from the start, the defining character of Johannesburg was its connection with the fabric, trends and cultural style of London, Paris and New York. Frisby's observation that ‘the culture of modernity became synonymous with the culture of the metropolis’27 rings true for Johannesburg. It was first and foremost a metropolis in every conceivable sense of the term. In fact, the entire history of its built structures testifies to ‘its inscription into the canons of modern Western urban aesthetics’.28

During the 1920s and 1930s, the council indeed embarked on a concerted effort at modernization,29 of which the construction of swimming baths was part. This article taps into this by demonstrating that the architectural form of swimming baths reflected these trends. As well as being functional – as manifested in contemporary design, facilities, construction, standardization and the implementation of new technologies – they became significant visible physical manifestations of the council's initiative to change white Johannesburg into a ‘modern city’. This notion is a leitmotiv throughout this article.

Finally, questions of ‘locality’, ‘place promotion’, ‘selling cities’ and ‘civic boosterism’ became a popular topic amongst geographers and historians.30 As public social spaces, swimming baths were physical manifestations of municipal grandeur and pride of the city. Indeed, the swimming bath, as a building type, was a cultural and architectural artifact31 to be celebrated. This article speaks to this aspect, emphasizing efforts to sell the Johannesburg of the 1930s.

Context

Subsequent to the South African War (1899–1902), Johannesburg experienced steady population growth and a marked economic upswing. However, it was especially after World War I that its economic potential was unleashed. The 1920s and 1930s witnessed major investment in the mines and expanding industries grew exponentially. Following the 1922 white miners’ strike, capitalists, supported by the government, were able to disempower the workforce.32 While the Great Depression impeded economic growth to a marked degree, Johannesburg experienced a massive economic boom after South Africa abandoned the gold standard in 1932. The world price of gold doubled and the Witwatersrand's mining-driven economy took off as a result of the reopening of previously marginal mines and the discovery of new reserves on the West Rand in 1935.33 Chipkin captured the economic mood and its impact: ‘it was part of that gold bondage that gave Johannesburg its exuberance and the trite name of “City of Gold”’.34

After this ‘economic miracle’, all economic records were broken.35 The sudden increase in wealth strengthened cultural and architectural connections with Europe and North America. Johannesburg entered the 1920s and 1930s with a bravura that supported its appetite for new – and preferably imported – ideas and trends.36 This was reflected in modernist multi-storey buildings, up-market retail stores and impressive skyscrapers, many built according to the Art Deco style. They became an ‘unmistakable imprint of contemporary New York of the 1930s’,37 and were given ‘favourable sobriquets such as “Wonder of the Modern World” and “Miracle of the Empire”’.38 ‘Place-sellers’ justifiably marketed Johannesburg as a ‘world city’.39 This mindset filtered down to the cultural landscape. Add theatres, cinemas, public parks, a zoo, racecourses and sport facilities, and a picture emerges of a city that worked hard, played hard and was not afraid to splash out on its pleasure palaces.40 Swimming baths and their design, built during this time, reflected this environment.

However, there was a darker side to this. The prosperity strengthened the geography of racial, cultural, economic and class segregation.41 Consequently, geographic expansion to accommodate the fast-growing population influx followed the same pattern. This arrangement had, of course, a major debilitating effect on the lives of Johannesburg's black population, reflecting the realities of racialized municipal politics. So, despite the enormous boost in Johannesburg's economy during the 1930s, little was spent on black recreational facilities. The council only opened the first public swimming bath for blacks at the Wemmer Hostel site in 1936.42

Johannesburg was thus fashioned as a British city. On a material level, architecture, monuments, naming of streets and suburbs were indistinguishable from those of Britain,43 reinforcing a sense of belonging. Similarly, British sporting culture heavily influenced South African sport, such as cricket and rugby. Swimming, likewise, was a British-inspired sport activity.44 All these factors impacted on the provision and design as well as structure of sport and leisure facilities, thus adding another component to Johannesburg's British identity.

Sharing the same identity, the so-called ‘labour aristocracy’, i.e. the English-speaking artisans and mine-workers with a ‘sense of “Britishness”’,45 settled in the south-east. Not at all part of this powerful identity were white Afrikaans-speaking miners and unskilled labourers. They lived mostly in the emerging suburbs to the south-west where housing was cheaper. They became known as the ‘poor whites’.46

Local political power was in the hands of English-speaking, middle-class males with extensive social and economic links to mining and trade47 and they controlled Johannesburg's municipal government for almost the entire twentieth century. They kept a tight rein on the management of the city. Aware of the latest technologies and practices and anxious to participate in international discourse, they embraced urban modernity and dominated public opinion on the architectural features of the city.48 Hence, political decisions on the layout and use of public open spaces – as well as swimming baths – were profoundly informed by British designs.49

Maud identified the core business of the council to ensure the wealth, health and happiness of its residents. However, according to him, until the late 1920s, the council neglected its obligation to health and happiness in favour of wealth.50 This criticism might have been too harsh. Since the 1900s, the council, as did the gold mining companies, accepted responsibility for allocating urban open spaces and building facilities for leisure activities.51 Indicative of the growing social awareness amongst council members, various types of recreational facilities such as tennis courts, bowling greens and, indeed, swimming baths were constructed.52

Further building and expansion

Maud earmarks 1928 as the year in which the council invested in major infrastructural improvements and community services. For example, storm water drainage and road construction were upgraded whilst building started on new gas works, a new electricity power station and a new library. Significantly, these projects were ‘the first-fruits of that fertilizing flood of capital expenditure which after 1927 the council poured out in more and more copious streams’.53

Bickford-Smith remarks: ‘By the early 20th century it had become the objective of civic authorities…to build aesthetically more pleasing cities, prompted by combined desire for private glory and communal benefit.’54 The building of six baths between 1927 and 1932 was part of this endeavour.55 As elsewhere, they would not solely be functional. They also became symbols of municipal modernity and tangible evidence of civic ideals and pride. Additionally, they were built for the public good and not for private gain. As in America and Britain, they would rank alongside town halls, parks, libraries and other major public buildings as showcases of municipal activity and place-selling.56 Not surprisingly then, Johannesburg obtained city status on 5 September 1928.57

Until 1921, Johannesburg only had one swimming bath for whites at Ellis Park, Doornfontein, built in 1908–09. Rising living standards amongst white suburbanites created an increase in the number of ratepayers who harboured demands of their own. For them, one swimming bath was inadequate for Johannesburg's fast-growing white suburbs. Hence, requests to build more baths became increasingly vociferous, especially in their demands that suburban school children should be catered for.58

In England, ratepayers’ associations indeed successfully contested but also supported plans for the built environment.59 Likewise, Johannesburg's white ratepayers’ associations became a force to be reckoned with. Their calls for higher-quality swimming facilities, such as treated water, and for an increase in the provision of municipal bathing facilities during the inter-war years, played an important role in realizing their demands.60

The first of these new baths was built at the so-called ‘Wemmer Pan’ in the suburb of Turffontein.61 Wemmer Pan was originally a quarry to the south of Johannesburg. Later, it became a popular leisure resort for fishing and yachting. The council readily approved the site,62 as the resort offered all the facilities for recreation in one convenient and accessible spot.63 In addition, the majority of the neighbouring suburbs favoured the development.64 It was envisioned that improvement plans ‘should rescue the Pan from its present comparative obscurity’.65 Subsequently, the council sanctioned £13,200 for the project.66 In addition, it acquired 35 acres of land adjacent to Wemmer Pan and the right to use the pan for pleasure boating.67

Councillor C.H. Brooks, chairman of the Parks and Estates Committee, was very proud of the transformation from a fairly underdeveloped pan to one that could now boast a ‘splendid bath’.68 The Star reported that the residents were soon to find that ‘Doornfontein is not the only pebble on the beach.’69 Members of the nearby communities had high hopes that the Wemmer Pan swimming bath and the other facilities on offer, such as the boats on the pan, would make it one of Johannesburg's principal pleasure resorts.70 This indeed happened. The popularity of the bath increased after a direct tram route from the city centre to Turffontein opened on 3 August 1923.71

In July 1927, courtesy of the administrator of the Transvaal Province,72 J.H. Hofmeyr,73 the council obtained a loan of £50,000, of which £25,000 was earmarked for additional swimming baths.74 This was a bonanza for the council because previously the municipal budget had to be balanced without any assistance from the provincial or the central government.75 The loan enabled the council to launch an extensive building programme to provide sporting facilities. The Rand Daily Mail lauded the administrator, who ‘recognized that Johannesburg is firmly resolved to keep abreast of the times in the matter of adequate facilities for improving the health and physique of its future residents’.76

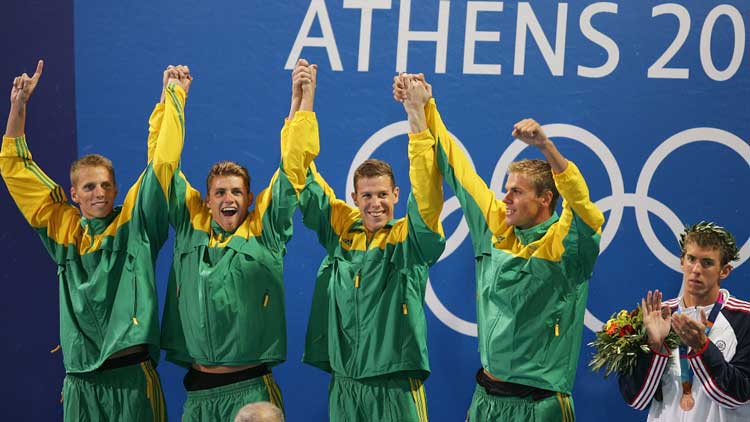

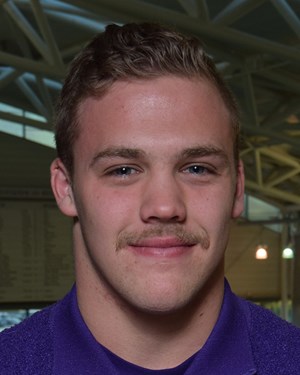

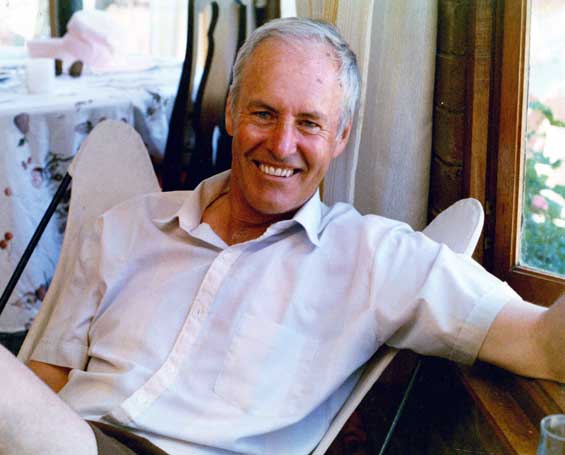

Based on this additional income, construction of three additional baths, commenced: at Zoo Lake (see Figure 1), Rhodes Park and Paterson Park.77 They were all near English-speaking middle-classes suburbs and in line with the council's policy to provide swimming baths according to local demands.

Figure 1. Zoo Lake swimming bath, 2020.

As was the case with similar purchases, the land thus served a dual purpose, for a park and a swimming bath.78 This was in keeping with the modern tendency to redefine the purpose of urban parks, as had become common practice in London.79 Ellis Park was the definitive example of a leisure space initially demarcated as a park and then being transformed into a space exclusively for sporting activities.80

Before the severity of the Great Depression impeded any ambitious economic development, a further three baths were constructed. The local sport clubs played a key role. For example, the Yeoville Sports Club used land already owned by the Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Co. The company was willing to transfer the land to the council, ensuring that a swimming bath could be built for use by residents of Yeoville and Observatory suburbs.81

The same philosophy that was followed in Yeoville was applied when the Mayfair and Malvern baths were built. Here, too, sport complexes were developed catering, inter alia, for football fields, cricket pitches and swimming baths.82 The council purchased the necessary land from the nearby Langlaagte Estate and Gold Mining Co. Ltd, an area of approximately 2½ acres, costing £50 per acre.83 Significantly, the Mayfair bath was the only one constructed in the south-western suburbs, where most of the residents were white working-class Afrikaans-speakers.84

As indicated earlier, the other swimming baths were in the prestigious northern and north-eastern suburbs, away from the industrial noise and grime of the city where white, middle-class English-speakers predominated. Ratepayers in these suburbs received preferential treatment in the provision of swimming baths from the council. This was in stark contrast to its provision in the poorer white Afrikaner working-class areas. Apart from the Mayfair swimming bath, only two additional swimming baths were built in these areas much later. Clearly, class and ethnic politics were at play in municipal circles. However, it must also be kept in mind that Afrikaners had no tradition of swimming. It was initially an English-speaking elitist sport, especially practised by the English-speaking communities on the coast, i.e. Durban and Cape Town. This tradition was maintained by English speakers in Johannesburg.

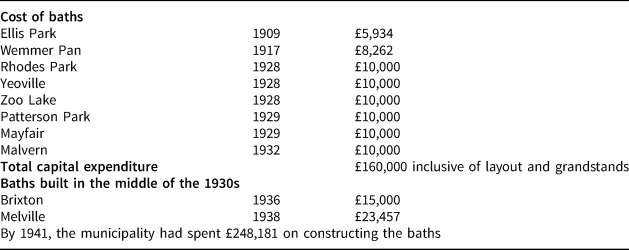

After negotiations with the Malvern Lawn Tennis Club, the council purchased two stands at £1,000.85 Despite the fact that the Malvern bath took another two years to complete, the Rand Daily Mail described it as yet another addition to Johannesburg's ‘generous number’ of baths.86 The total capital expenditure to construct all these baths was £160,000,87 indicating the commitment of the council to invest in the baths.

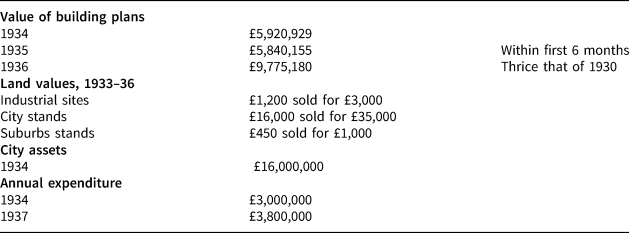

As indicated, after South Africa left the gold standard, the positive effect on Johannesburg's economic growth was dramatic. The property and the building industry reflected this with some prices quadrupling between 1930 and 1936 (Table 1).

Table 1. An indication of Johannesburg's phenomenal economic growth in the mid-1930s

Source: Wits/WCL, Municipal Magazine, 17 (1934), 1; 18 (1934), 7; 18 (1935) 5, 11, 23; 19 (1936), 5, 7; and 20 (1937), 15.

Johannesburg thus became a city where there was plenty of money for such projects. Within this context, the further provision of swimming baths became possible, as the budget for 1930 reflected.88 However, this would take another few years to come to fruition and was realized only in two suburbs.89 A report laid before the council in June 1936 stated that because of the increase in the population in the north-western areas, the Mayfair swimming bath was inadequate. The upshot was that the council approved the construction of swimming baths in the Brixton and Melville suburbs.90

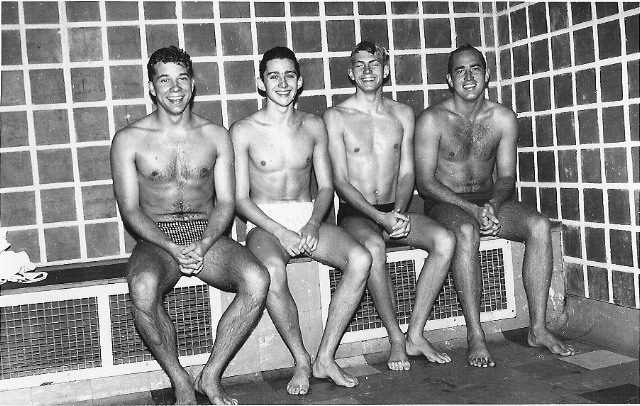

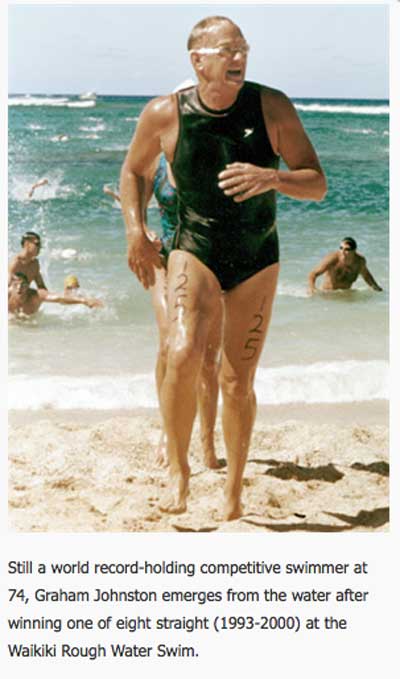

In Brixton, the land belonged to the council, which eased the pressure on its coffers significantly.91 However, this was not the case in Melville. The council had to purchase a site, of 7¾ acres for £285 per acre,92 for the construction of the proposed swimming bath. It would, however, take another three years to complete (see Figure 2).93 The Brixton and Melville projects wrapped up the council's major scheme of providing swimming baths.

Figure 2. Brixton swimming bath, reflecting Art Deco architectural style.

Design, construction and maintenance

The growth in aquatic sport and training, as well as recreational use of the baths, informed additional needs and demands for swimming baths in the 1930s. F.R. Long, president of the Association of Superintendents of Public Parks and Gardens, was well aware of the changing demands for parks and open spaces of the ‘leisured section’ of Johannesburg's ratepayers. Due to shorter working hours, leisure time and demand to spend these hours outdoors increased. Long acknowledged that ‘the phenomenal growth of our parks, open spaces and swimming baths has already caught us to some extent unawares…The ratepayers now also want their golf, bowls, tennis and bathing facilities.’94

The 1920s and 1930s can well be considered the most exciting era in swimming bath design.95 The popularization of swimming and of water polo as spectator sports had a marked effect on the design and accessorization of baths. New reinforced concrete construction and Art Deco style – that lent itself well to recreational architecture – ensured that swimming baths became an ‘iconic symbol of 1930s municipal glamour’.96 The purpose-built, open-air Tooting Bec Lido97 was representative of these modern ideas on hygiene, beauty of design, layout, comfort and recreation.98 In New York, no expenses were spared in the quality of the baths built during this time, ‘each pool turned out to be a “municipal marvel of the first magnitude”’.99 Although not as lavish, Johannesburg's swimming baths of the 1930s did not lag behind.

The council deliberately sanctioned additional funds for the layout of the grounds surrounding the swimming bath.100 A reporter of the Rand Daily Mail confirmed that, ‘Apart from the delights of the cool water, the baths are each year being made more attractive.’101 As sunbathing became increasingly popular, specific areas for this purpose now formed part of the layout.102 This replicated the New Brighton Lido, where a huge area was devoted to open benches and specific sunbathing zones, enabling people to develop ‘bronzed’ bodies.103

The director of the local Parks Department, D. Smith, in comparing these facilities with similar ones in England and Scotland, concluded that Johannesburg's baths were even better as few of the overseas baths, he claimed, had lawns, gardens and facilities for sunbathing.104 As form and function changed, the design, fabric and construction of baths adjusted accordingly.105 Clearly, the town engineer's recommendation that the best baths be constructed, conforming to international competitive standards, was adhered to.106 This was another attempt by the council to stake the city's claim as a ‘world class city’.

The amenities at the baths reflected a ‘differential architecture’ in two ways. First, there was a gendered differential, i.e. ‘male’ and ‘female’ sections. Secondly, separate changing cubicles (‘dressing boxes’) were installed around the bath's perimeter with clearly distinguishable private spaces. This resulted in what Crook describes rather quaintly as an ‘interplay of exposure and enclosure’.107 The amenities at the Wemmer Pan swimming bath, as well as subsequent baths, reflected both these requirements. With the introduction of mixed bathing,108 and the consequent need for more personal privacy, separate dressing cubicles were built for women and men. This planning had the additional advantage of ‘proper supervision’.109

One of the age-old problems in swimming bath management is water quality. Before the twentieth century, water quality was maintained through the so-called ‘fill and empty’ process. This meant that the baths were emptied on a Sunday and filled again on a Monday with fresh water. According to Bowker, this weekly water change meant that there were ‘fresh water days’ and ‘dirty water days’.110 As no other process was available at the time, this system was also implemented at the Ellis Park bath, necessitating the closure of the bath on a Sunday afternoon and the following Monday.111

By the late nineteenth century, the ‘germ theory’ and a growing corpus of bacteriological and chemical studies112 resulted in major technological advances in water purification, thus quelling concerns about ‘dirty water’.113 Furthermore, a system of recirculating to disinfect the water through filtration114 was developed.115 Well aware of the problem, Johannesburg's municipality installed such a water purifying system at the Ellis Park bath in October 1922, at a cost of £5,000.116 The introduction of chlorine in the 1930s was the final step in a process whereby baths brought hygiene to the masses. As a consequence, there was a rise in recreational swimming.

The Star quelled any doubts the public might have had, maintaining that the ‘water in which Johannesburg swimmers bathe is actually purer than drinking water’.117 Love's observation that ‘to bathe, wash or swim in clean water is an obvious antidote to contact with the dirt of contemporary urban life’118 rings true of Johannesburg, being afflicted by unhygienic air, often laden with mine dust. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, a high standard of water quality seven days a week was maintained.119 This was another demonstration of the progress in new and modern technology of which Johannesburg was now part.

Furthermore, the council committed itself to frequent maintenance of the baths which were renovated and painted regularly.120 According to the Rand Daily Mail, few people realized the enormous amount of work necessary in maintaining the swimming baths. During the closed season, there were ‘armies’ of workmen busy with maintenance of the baths.121 This ensured that the baths were indeed an asset to the fabric of a respectable and modern city.

In 1928, the Ellis Park bath was earmarked for extensive modernizing in accordance with international requirements.122 Due to financial constraints,123 these improvements were only completed in 1938, but once completed did indeed include most of the envisioned improvements suggested in 1928.124 The new modernistic building now boasted, inter alia, a children's paddling pool, modern change cubicles, a three-tiered water cascade, an impressive fountain in the centre of an enlarged lawn and a special sunbathing porch, where ‘bathers and worshippers of “King Sol” may bask undisturbed’.125 Suntans, once derided in fashionable circles, ‘became a badge of health and glamour’, gaining momentum during the 1930s.126 This point did not escape Geo Neal Luntz. He linked the context of living in Johannesburg and the necessity for a swimming bath as follows: ‘In a climate such as ours…the hot weather enables bathers to remain much longer in the water, thus obtaining a double benefit from the exercise of swimming and for exposure to the sun – one of the great benefits of bathing.’127

Special attention was given to facilities for diving, the council approving a hefty £10,000 for a modern high-diving platform128 that complied with international regulations,129 making it possible for Ellis Park to host South African national and international diving events.130 A.C.C. St Norman, the superintendent of the baths, was astonished that the council had indeed been so successful in undertaking these extensive additions.131

According to Van Leeuwen, swimming baths ‘make an indispensable contribution to the reading of twentieth-century architectural modernism’,132 whilst Marino points out that they were seen as ‘grand gestures…demonstrating the municipal power of a progressive city’.133 When considering the attention to the layout, amenities, new water purification technologies and consciously ensuring that international standards were met, the same was true for Johannesburg's swimming baths as features of a modern city. In addition, a variety of the latest in modern durable materials were introduced into swimming bath construction either for the first time or in new ways. In a sense, the baths became modern, standard and commonplace at the same time. Smith had reason to believe that Johannesburg's swimmers had ‘as favourable and modern conditions as any in the world’.134 The fact that swimming baths were a very expensive item on the Parks and Recreation Department's budget underscores their importance to the council (see Table 2).135 Foster quotes Mitchell who situates the modern city as part of an ‘exhibitionary complex’, a product of bourgeois capitalism.136 The swimming baths were part of this complex, mirroring urban Johannesburg's modernity of the 1920s and 1930s.

Table 2. Cost of building Johannesburg's swimming baths and an indication of rising prices

Sources: MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 200th meeting 27 May 1908, 1224–7; 514th meeting 22 Jan. 1929, 36; 603th meeting 23 Jun. 1936, 822–3; 635th meeting, 28 Feb. 1939, 204; Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 12 Aug. 1929, Star, 22 May 1930, Star, 18 Oct. 1938, Star, 30 Aug. 1941; file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1932; file 320, RDM, 10 Oct. 1932; file 452, RDM, 20 Nov. 1935, RDM, 4 Jul. 1936.

Bringing Johannesburg's swimming baths, and especially the Ellis Park bath, up to date with international standards137 was thus not incidental. Contextually, it was part of an elaborate project to showcase Johannesburg as a renowned, modern and international city, that reached its climax with Johannesburg's 1936 Empire Exhibition. Elaborate brochures from the Johannesburg Publicity Association and the Tourist Bureau of the South African Railways reflected, promoted and celebrated Johannesburg's ‘Metropiltan modernity’.138 The exhibition ‘was celebrating an urban modernity – the success of Johannesburg's progress’ frequently being described as a ‘wonder city’ or a ‘glorious new city’ on a grand scale.139 The modern swimming baths were thus one of the building blocks of the city's image and an important component of place-selling.140

Swimming lessons and training

By the late 1890s, the provision of swimming baths in most towns and cities in Britain meant that swimming was included in the school time table.141 Gradually, the necessity for more advanced training in swimming by professional trainers developed.142 In Johannesburg, even before the first swimming bath was built, the need for professional swimming instructors was acknowledged.143 The council appointed J. Hancock as the first municipal swimming instructor in 1931, thus making it possible for everyone to learn how to swim free of charge.

Five years later, realizing the importance of swimming lessons, the council appointed J.W. Harte, a well-known Olympic swimming coach from the United States, for two years at salary of £600 a year.144 Sue G. Womble145 congratulated the council on Harte's appointment, saying that his expertise was welcome because the bath superintendents were not as skilled in ‘the finer art of swimming’. For her, his appointment made sense as South Africa ranked very low in the world of swimming.146 By engaging Harte, the council hoped to popularize swimming and swimming competition, thus making full use of the swimming baths.147

Harte's coaching gave Johannesburg's swimmers, as well as swimming in South Africa, a major boost, resulting in 10 national records being broken in 1937 and placed South African swimmers and coaches on a par with their counterparts in other parts of the world.148 Johannesburg could now boast that its white swimmers could compete internationally and that its swimming baths matched international standards. This was another feather in its cap to its image as a modern progressive city.

Popularity

By 1924, the Ellis Park bath had already established its popularity among adults and children alike. So much so, that on Saturday afternoons and Sundays, the crowds caused considerable congestion.149 ‘Swimmer’ complained that Sundays were so crowded ‘that it is uncomfortable, not to say unpleasant bathing’.150 ‘Swimmer’ was indeed correct. For example, 1,600 people frequented the bath on one of the Sundays in March 1919,151 and on a Sunday in January 1927, ‘K.T.’ had to wait over an hour to get a booth because as many as 4,000 people ‘went into the water’.152 One Harry Melman looked at the positive side of the congestion, emphasizing that the swimming bath was ‘doing extremely well, as it is always crowded to the utmost’.153

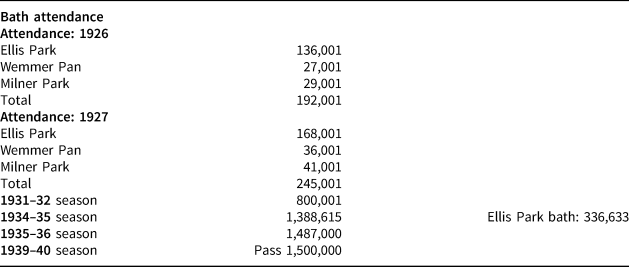

In the 1930s, the municipal baths maintained their popularity, with many of the reports indicating that the baths were a major attraction and were usually crowded (see Table 3). For instance, the Star claimed that at the beginning of spring in September 1931, crowds flocked there to cool off not only on Sundays but in the late afternoons on other days.154 There were also large numbers of early swimmers who frequented the baths before breakfast.155 The swimming baths were becoming increasingly popular, reaching the 2 million mark for attendance during the 1946 season.156

Table 3. Popularity of swimming baths, measured by growth in attendance

Source: Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 4 Jan. 1928; file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1932, Star, 3 Sep. 1933, RDM, 1 Sep. 1943, RDM, 30 Aug. 1947; file 452, Star, 12 Nov. 1935, Star, 31 Aug. 1936; file 447, Star, 30 Aug. 1941; Wits/WCL, Municipal Magazine, 20 (1936), 11.

On the one hand, ‘going to the baths’ meant serious training for competitions while, on the other hand, the majority of patrons partook in the more quotidian forms of play – splashing, play fighting and flirting. The proximity and accessibility of the baths influenced the lifestyle of many: Saturdays and Sundays became ‘fun days’ for families.

Several factors contributed to the popularity of the swimming baths. From early on, the various swimming clubs,157 such as those run by Post Office and municipal staff, groups of ladies and many schools, ‘were the life-blood in maintaining the popularity of the baths’.158 Their regular patronage guaranteed the sustainability of the baths.159

Furthermore, petrol restrictions during World War II and consequent shortages contributed to these numbers. More people chose to visit the baths during the weekends than picnic in the country.160 A major debate raged in the 1930s over whether men should be allowed to wear trunks as swimwear. The council enforced a strict ban that was eventually lifted in the early 1940s. This did much to further increase the baths’ popularity.161

In assessing the popularity of the baths, the number of spectators should also be considered. The public enjoyed watching swimming galas,162 the numbers attending sometimes outstripping those actually using the bath. The baths evolved from being a place solely devoted to health, to one geared towards recreation, sport and, now, entertainment. For urban dwellers, it was an inexpensive amusement spectacle, somewhere that people could witness the abilities of talented professional swimmers. It became a convenient leisure activity and provided another opportunity for social integration. This was aided by the fact that the baths were designed as places for viewing and amusement as much as for swimming.163 Katzer's statement that ‘the stadium or whole ensembles of sports arenas, facilities and landscapes served as places of social transformation’164 comes to mind.

School galas, in particular, were very popular. The Melville bath is a case in point, being ‘the most popular bath in Johannesburg’.165 Its popularity with spectators increased as the bath was open on certain nights as well when the Swimming League gave demonstrations. Enthusiastic crowds attended competitive swimming such as the Transvaal Amateur Swimming championships held early in 1940.166 Gordon and Inglis remarked that, in Britain, ‘By tapping into the public's seemingly insatiable appetite for entertainment and sporting activity, baths…evolved into multi-purpose events venues.’ 167 This proved to be true for Johannesburg, as confirmed by the Ellis Park sport venue.

Conclusion

The growth in the number of swimming baths in the 1920s and 1930s was enabled by the rapid geographical expansion of the city and its economic growth – backed by mining and industrial development. Johannesburg's swimming baths reflected a divided society based on race, class and culture. Black Johannesburgers did not have access and all but three swimming baths were built in middle-class suburbs and steeped in an all-pervasive British ethos.

The council, as the main protagonist, comprising white English-speaking men, wielded enormous powers. Nevertheless, they had the well-being of the white residents at heart. The provision of services such as electricity, water and sanitation testified to that. Establishing leisure facilities turned out to be just as important. For example, by the 1920s, public parks had become a standard feature in Johannesburg's white suburbs.168 Swimming baths now became the prime focus adding another layer to the leisure facilities of these suburbs, changing the suburban landscape. Despite economic restrictions, especially in the late 1920s, the council was eager to drive the process and pushed ahead. Expenses on swimming baths comprised by far the main overhead of the city council's Parks and Recreation portfolio.

This was aided by the growing popularity of and interest in swimming and other aquatic sports. As such, the council had to take note of the pressure from suburban residential associations and sport clubs to build additional swimming baths. They fitted seamlessly into the council's plans and endeavours to modernize Johannesburg, mirroring modern designs, facilities, construction, standards and the implementation of new technologies similar to those in Britain and the United States. Accordingly, they became additional threads in a rapidly evolving modern urban tapestry which the council was eager to celebrate and showcase.

In addition to Johannesburg's parks, tennis courts and golf courses, swimming baths significantly added to the suburban landscape's leisure facilities. They indeed became, and henceforth remained, what Bale coins urban ‘sportscapes’.169 As residents were now close to the baths, they became very popular, frequented for competitive and recreational purposes. The council further invested in the swimming baths by making special arrangements to cater for the youth, such as providing coaching.

Doyle captured an emergent trend in urban studies by emphasizing that ‘the interaction of health and the environment is back on the agenda in a big way’.170 It is precisely in this relevant and topical area that the article sought to contribute.

References

1

On the use of nomenclature, whilst the secondary sources use the terms ‘lido’, ‘baths’ or ‘pool’, for this article, the term ‘baths’ was chosen as the primary sources used this term. They have all long been interchangeable.

2

R.E. Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools in America, 1800–1940, with emphasis on standards and practices for indoor pools, 1910–1940’, Cornell University Ph.D. thesis, 2010, 1.

3

- Van Leeuwen, The Springboard in the Pond: An Intimate History of the Swimming Pool(Boston, MA, 1998), 12.

4

- Wiltse, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America(Chapel Hill, 2007).

5

- Love, A Social History of Swimming in England, 1800–1918: Splashing in the Serpentine(London, 2007).

6

Kozma, G., Teperics, K. and Radics, Z., ‘The changing role of sports in urban development: a case study of Debrecen (Hungary)’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 31 (2014), 1118CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

7

- Batstone, ‘Health and recreation: issues in the development of bathing and swimming, 1800–1970, with special reference to Birmingham and Thetford Norfolk’, University of Birmingham Ph.D. thesis, 2002; Kossuth, R.S., ‘Dangerous waters: Victorian decorum, swimmer safety, and the establishment of public bathing facilities in London (Canada)’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 22 (2005), 796–815CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Marino, G., ‘The emergence of municipal baths: hygiene, war and recreation in the development of swimming facilities’, Industrial Archaeology Review, 32 (2010), 35–45CrossRefGoogle Scholar; F.H. McLachlan, ‘Poolspace: a deconstruction and reconfiguration of public swimming pools’, University of Otago Ph.D. thesis, 2012; McShane, I., ‘The past and future of local swimming pools’, Journal of Australian Studies, 33 (2009), 195CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools’, 1.

8

- Mbembe and S. Nuttall, ‘Writing the world from an African metropolis’, Public Culture, 16 (2004), 353.

9

Ibid., 356.

10

This is confirmed by the fact that the first swimming bath for black people was only built in 1936.

11

Parnell, S. and Mabin, A., ‘Rethinking urban South Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 21 (1995), 39–62CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12

Bickford-Smith, V., ‘Urban history in the new South Africa: continuity and innovation since the end of apartheid’, Urban History, 35 (2008), 300CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Freund, B., ‘Urban history in South Africa’, South African Historical Journal, 52 (2005), 26CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

13

- Bickford-Smith, The Emergence of the South African Metropolis. Cities and Identities in the Twentieth Century(Cambridge, 2016), 8 and 19.

14

Gunn, S., ‘Class, identity and the urban: the middle class in England, c. 1790–1950’, Urban History, 31 (2004), 29CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Also see Lewis, R., ‘Comments on urban agency: relational space and intentionality’, Urban History, 44 (2017), 141–4CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15

The suburb had become a significant object of study as confirmed by the recent work of Stone (D. Stone, ‘Suburbanization and cultural change: the case of club cricket in Surrey, 1870–1939’, Urban History, 44 (2017), 48). Also see M. Clapson, ‘The new suburban history, New Urbanism and the spaces in between’, Urban History, 43 (2016), 336–41.

16

Gunn, ‘Class, identity and the urban’, 39.

17

- Beavon, Johannesburg: The Making and Shaping of the City(Pretoria, 2004), 88–92. McManus and Etherigton repudiate the classic picture of the ‘bourgeois enclave’ (R. McManus, and P. Etherigton, ‘Suburbs in transition: new approaches to suburban history’, Urban History, 34 (2007), 317–18, 322). As indicated, however, this did not apply to Johannesburg where suburbs carried an exclusive race and class distinction.

18

- Bowker, ‘Parks and baths, sport recreation and municipal government and the working class in Ashton-under-Lyne between the wars’, in R. Holt (ed.), Sport and the Working Class in Modern Britain(Manchester, 1990), 84.

19

McShane, ‘The past and future of local swimming pools’, 195; and N. Katzer, ‘Introduction: sports stadia and modern urbanism’, Urban History, 37 (2010), 249.

20

B.M. Doyle, ‘A decade of urban history: Ashgate's Historical Urban Studies series’, Urban History, 36 (2009), 501–2, 505.

21

- Couperus, ‘Research in urban history: recent theses on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century municipal administration’, Urban History, 37 (2010), 322.

22

- Robinson and P. Taylor, ‘The performance of local authority sports halls and swimming pools in England’, Managing Leisure, 8 (2003), 1.

23

- Love, ‘Local aquatic empires: the municipal provision of swimming pools in England, 1828–1918’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 24 (2007), 620; and C. Love, ‘Holborn, Lambeth and Manchester: three case studies in municipal swimming pool provision’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 24 (2007), 630–42.

24

McShane, ‘The past and future of local swimming pools’, 195.

25

- Brooks and P. Harrison, ‘A slice of modernity: planning for the city and the country in Britain and Natal, 1900–1950’, South African Geographical Journal, 80 (1998), 93–100; and D. Scott, ‘“Creative destruction”: early modernist planning in the south Durban industrial zone, South Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 29 (2003), 235–59.

26

Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 79.

27

- Frisby, Cityscapes of Modernity: Critical Explorations(Cambridge, 2001), 161.

28

Mbembe and Nuttall, ‘Writing the world’, 361.

29

C.M. Chipkin, Johannesburg Style: Architecture and Society, 1880s–1960s (Cape Town, 1993), 10.

30

P.J. Larkham and K.D. Lilley, ‘Plans, planners and city images: place promotion and civic boosterism in British reconstruction planning’, Urban History, 30 (2003), 184; C.W.J. Withers, ‘Place and the ‘‘spatial turn’’ in geography and in history’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 70 (2009), 638. For South African cities, see Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 131.

31

Van Leeuwen, The Springboard in the Pond, 12.

32

- Hyslop, ‘The imperial working class makes itself “white”: white labourism in Britain, Australia, and South Africa before the First World War’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 12 (1999), 398–421.

33

J.R. Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg (Johannesburg, 1966), 358.

34

C.M. Chipkin, Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950 (Newtown, 2008), 99.

35

Beavon, Johannesburg, 93 and 110. See Bickford-Smith for the growth in gold production. Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 30.

36

- Foster, ‘The wilds and the township: articulating modernity, capital, and socio-nature in the cityscape of pre-apartheid Johannesburg’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 71 (2012), 43. In considering how to achieve greater urban order and improvement, municipalities constantly drew on ideas and practices from abroad. These informed initiatives like provision of recreational space. Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 155.

37

G.-M. Van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis: The Buildings of Johannesburg, 1886–1940 (Melville, 1986), 168; and M. Latilla, Johannesburg: Then and Now (Cape Town, 2018), 73 and 29.

38

Van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis, 171–2.

39

Chipkin, Johannesburg Style, 90; and Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 189.

40

- Van Rensburg, Johannesburg. Eenhonderd Jaar(Johannesburg, 1986), 53, 58, 59, 168, 177, 187.

41

In 1936, there were 230,566 (or 40.7 per cent) Afrikaans-speakers and 290,853 (or 51.4 per cent) English-speakers in Johannesburg, thus confirming the continued dominance of British political, social and cultural power in the city (E.L.P. Stals, Afrikaners in die Goudstad, Deel 2, 1924–1961 (Pretoria, 1986), 11).

42

J.P.R. Maud, City Government: The Johannesburg Experiment (Oxford, 1938), 149. For a more extensive discussion of sport and recreational facilities for blacks, see A.G. Cobley, The Rules of the Game: Struggles in Black Recreation and Social Welfare Policy in South Africa, Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies, 182 (Greenwood, 1997), 27–30; and C.M. Badenhorst, ‘Mines, missionaries and the municipality: organised African sport and recreation in Johannesburg c. 1920–1950 (Ann Arbor, 1994).

43

- Lambert, ‘South African British? Or Dominion South Africans? The evolution of an identity in the 1910s and 1920s’, South African Historical Journal, 43 (2000); J. Lambert, ‘“An unknown people”: reconstructing British South African identity’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 37 (2009), 604; and Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 8, 19, 69, 76.

44

- Love, ‘“Taking a refreshing dip”: health, cleanliness and the empire’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 24 (2007), 704.

45

- Harrison and T. Zack, ‘Between the ordinary and the extraordinary: socio-spatial transformations in the “old south” of Johannesburg’, South African Geographical Journal, 96 (2014), 184.

46

Beavon, Johannesburg, 88, 110, 117; and Stals, Afrikaners in die Goudstad, 19–20, 22.

47

Maud, City Government, 162.

48

Stals, Afrikaners in die Goudstad, 14, 50, 108, 148.

49

Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 12, 155. Pick observed a similar phenomenon for American cities. Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools’, 36.

50

Maud, City Government, 111.

51

- Grundlingh, ‘“Parks in the veld”: the Johannesburg Town Council's efforts to create leisure parks, 1900s–1920s’, Journal of Cultural History, 26 (2012), 83–105; L. Grundlingh, ‘“Imported intact from Britain and reflecting elements of empire”: Joubert Park, Johannesburg as a leisure space, c. 1890s–1930s’, South African Journal of Art History, 30 (2015), 94–118; L. Grundlingh, ‘Transforming a waste land to a world class sporting arena – the case of Elllis Park Johannesburg 1900–1930s’, Historia, 62 (2017), 27–45; and L. Grundlingh, ‘“In Johannesburg, baths are a necessity, not a luxury.” The establishment of Johannesburg's first municipal swimming bath, 1900s–1910s’, New Contree, 81 (2018), 1–26.

52

Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg, 653; and Van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis, 216.

53

Capital expenditure rose from £221,599 in 1926/27 and passed a million pounds in 1930/31. Maud, City Government, 85.

54

Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 12.

55

Nearby municipalities, such as Germiston and Benoni, already had swimming baths and regularly hosted swimming and water polo competitions. Similar competitions took place at swimming baths at the mines. Readex Newsbank, Rand Daily Mail, 23 Feb. 1903, 14 Mar., 14 and 28 Dec. 1904.

56

- Glassberg, ‘The design of reform: the public bath movement in America’, American Studies, 20 (1979), 19; I. Gordon and S. Inglis, Great Lengths: The Historic Indoor Swimming Pool of Britain(Swindon, 2009), 12, 51, 173; and J. Smith, Liquid Assets: The Lido and Open Air Swimming Pools of Britain(London, 2005), 19.

57

Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg, 350.

58

University of the Witwatersrand, William Cullen Library, Historical Papers (Wits/WCL/HP), AF 1913, Johannesburg Public Library Paper Clippings (JPLPC), file 320, Rand Daily Mail (RDM), 26 Dec. 1921.

59

D.J. Ellis, ‘Pavement politics: community action in Leeds, c. 1960–1990’, University of York Ph.D. thesis, 2015, 7–26.

60

Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools’, 33; and Bowker, ‘Parks and baths’, 86.

61

The pan was south of a major mining complex and was also known as Pioneer Park. See G.H.T. Hart, ‘An introduction to the anatomy of Johannesburg's southern suburbs’, South African Geographical Journal, 50 (1968), 65–72, for a description of this area.

62

Municipal Offices, Johannesburg, Law Library, minutes of the town council (MO/Jhb/LL, MTC), 349th meeting, 2 Nov. 1917, 613. As a result of World War I, the plan was postponed.

63

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, Star, 25 Jan. 1920.

64

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 395th meeting, 12 Oct. 1920, 727. By now, Afrikaans-speaker working-class families also settled in the southern suburbs such as Forest Hill, La Rochelle and Turffontein with Jews and Portuguese. The area thus represented a cosmopolitan character. Stals, Afrikaners in die Goudstad, 21.

65

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, Star, 5 Jan. 1920.

66

This was a substantial amount, being more or less £650,000 in today's terms.

67

Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg, 652. Noteworthy is the fact that, due to earlier property development, the council barely ‘owned’ any land. Maud, City Government, 263. Consequently, obtaining land for recreational purposes became a costly affair.

68

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 28 Dec. 1921.

69

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, Star, 22 Nov. 1921.

70

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, Star, 4 Apr. 1922.

71

Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg, 895.

72

After 1994, the Transvaal Province was divided into four provinces: Gauteng, North-West, Limpopo and Mpumalanga.

73

He was administrator of the Transvaal from 1924 to 1929.

74

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 8 Jul. 1927. The previous year, the Parks and Estates Committee only received £7,000, which was £20,000 short of the budget (Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 26 Jul. 1927).

75

Maud, City Government, 290.

76

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 8 Jul. 1927. The city's white residents were fairly healthy. The death rate amongst the city's white residents was 10 per 1,000. Address by the medical health officer of Johannesburg, Dr Charles Porter, 2 Feb. 1925. Wits/ WCL/ HP, A3023, S. Parnell Papers, 1906–99, A2, Municipal Magazine, Aug. 1925, 17b. This figure remained steady between 1923 and 1936. In contrast, the death rate amongst blacks fluctuated between 17 and 23 per 1,000. Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 186.

77

Zoo Lake bath served the Parkview, Parktown North, Parkwood, Rosebank and Melrose suburbs (MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 504th meeting, 27 Mar. 1928, 170), Rhodes Park bath the Kensington suburb and Patterson Park bath the Orange Grove and Norwood suburbs (MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 510th meeting, 25 Sep. 1928, 755).

78

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, Star, 25 Jan. 1928.

79

M.O. Hannikainen, ‘Sport in London's public green spaces in the inter-war years’, Sport in History, 38 (2018), 331–64.

80

Grundlingh, ‘Transforming a waste land’, 27–45.

81

MO/Jhb,LL, MTC, 518th meeting, 28 May 1929, 447–8.

82

Maud, City Government, 149 and 352.

83

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 514th meeting, 22 Jan. 1929, 36.

84

F.S. Parnell, ‘Council housing provision for whites in Johannesburg, 1920–1955’, University of the Witwatersrand, MA thesis, 1987, 38.

85

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 534th meeting, 25 Sep. 1930, 820.

86

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1932.

87

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1931. To put this into perspective, to only run and maintain the swimming bath at Ashton-under-Lyne came to £80,000 during the inter-war years, an amount Bowker described as ‘costly’. Bowker, ‘Parks and baths’, 85.

88

Shorten, Die Verhaal van Johannesburg, 535–6.

89

It is not clear why more swimming baths were not built during the initial period of prosperity in the mid-1930s. Van der Waal is of the opinion that it was perhaps ‘due to a diminished social awareness during the prosperous years’. Van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis, 216.

90

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 603th meeting, 23 Jun. 1936, 822–3. Johannesburg's white population doubled from 250,000 to half a million between 1932 and 1937. Wits/WCL, Municipal Magazine, 20 (1937), 15.

91

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 20 Nov. 1935.

92

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, special meeting, 6 Oct. 1936, 1238. This was decidedly more than the £50 per acre paid for the Mayfair bath.

93

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 644th meeting, 21 Nov. 1939, 1531.

94

Wits/WCL, Municipal Magazine, 19 (1936), 13–15. Wiltse makes a similar point regarding America. Wiltse, Contested Waters, 93.

95

Gordon and Inglis, Great Lengths, 175.

96

- Pussard, ‘Historicising the spaces of leisure: open-air swimming and the lido movement in England’, World Leisure Journal, 49 (2007), 180.

97

Lidos, apart from the swimming bath, included cafes, fountains, ballrooms and sunbathing terraces. Pussard, ‘Historicising the spaces of leisure’, 181; and K. Worpole, Here Comes the Sun: Architecture and Public Space in Twentieth Century European Culture (London, 2000), 113.

98

For a detailed discussion of British baths, see Smith, Liquid Assets.

99

- Adiv, ‘Paidia meets Ludus: New York City municipal pools and the infrastructure of play’, Social Science History, 39 (2015), 437.

100

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 521st meeting, 27 Aug. 1929, 704, and MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 526th meeting, 25 Jan. 1930.

101

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1931.

102

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 580th meeting, 24 Jul. 1934, 813.

103

Marino, ‘The emergence of municipal baths’, 41.

104

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, Star, 31 Oct. 1934, and Wits/WCL, HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, Star, 3 Sep. 1938. In America, bath design also catered for leisure spaces. Hence, ‘lounging, sunbathing, and socializing became quintessential pool activities’. Wiltse, Contested Waters, 88, 99.

105

Marino, ‘The emergence of municipal baths’, 39; and C. Parker, ‘Improving the “condition” of the people: the health of Britain and the provision of public baths 1840–1870’, Sports Historian, 20 (2000), 36.

106

The baths were all constructed with concrete walls, lined on the sides with glazed tiles and the bottom of concrete blocks. MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 398th meeting, 21 Jan. 1921, 46.

107

- Crook, ‘“Schools for the moral training of the people”: public baths, liberalism and the promotion of cleanliness in Victorian Britain’, European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire, 13 (2006), 31, 38. Also see Kossuth, ‘Dangerous waters’, 807; and H. Eichberg, ‘The enclosure of the body. On the historical relativity of health, nature and the environment of sport’, Journal of Contemporary History, 21 (1986), 110.

108

In Johannesburg, mixed bathing became common practice as early as 1914. The only exception was that Friday afternoons were exclusively for women and Sundays for men. MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 297th meeting, 24 Apr. 1914, 217. This was in sharp contrast to the United Kingdom where many baths set aside just a few hours per week for women. A.C. Parker, ‘An urban historical perspective: swimming a recreational and competitive pursuit 1840 to 1914’, University of Stirling, Ph.D. thesis, 2003, 107–8.

109

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 395th meeting, 12 Oct. 1920, 727.

110

Bowker, ‘Parks and baths’, 87. Hayes confirms that the early baths were indeed known for their ‘dirty water’. W. Hayes, ‘The professional swimmer, 1860–1880s’, Sports Historian, 22 (2002), 137.

111

Grundlingh, ‘Transforming a waste land’, 20.

112

Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools’, 57. Also see M.T. Williams, Washing ‘The Great Unwashed’: Public Baths in Urban America (Columbus, 1991), 129.

113

Love, ‘“Taking a refreshing dip”’, 701–2.

114

It was known as the Turnover System and was supplied by the Turnover Filter Co. of Belfast.

115

Batstone, ‘Health and recreation’, 111.

116

Wits/WCL/ HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 27 Oct. 1922.

117

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, Star, 23 Aug. 1923. In America, the poor image of swimming bath water was fought with campaigns, advertising the magic of modern filtering techniques with the slogan ‘Some people drink filtered water. We bathe in it.’ Van Leeuwen, The Springboard in the Pond, 46.

118

Love, ‘“Taking a refreshing dip”’, 694.

119

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 1 Sep. 1937.

120

MO/Jhb/LL, MTC, 525th meeting, 17 Dec. 1929, 1056; Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 31 Aug. 1936; Wits/WCL/ HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, Star, 3 Sep. 1938; and Wits/WCL/ HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 307, RDM, 22 Aug. 1940.

121

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 1 Sep. 1937; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 31 Aug. 1938.

122

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 4 Jan. 1928.

123

Wits/WCL, Municipal Magazine, 18 (1935), 11.

124

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 4 Jul. 1936; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, Star, letter from ‘Patron’, 11 Sep. 1937.

125

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, Star, 12 Jan. 1938; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 26 Aug. 1938.

126

Gordon and Inglis, Great Lengths, 170.

127

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 9 Aug. 1917.

128

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 4 Jul. 1936.

129

By this time, all swimming baths had diving platforms as standard equipment. Marino, ‘The emergence of municipal baths’, 41; and Smith, Liquid Assets, 35.

130

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 17 Sep. 1937. Worpole points out that the ‘cult of diving’ reached its apotheosis between the wars, epitomized in Riefenstahl's film made of the 1936 Olympic Games, where the diving sequences astonished cinema audiences by their breath-taking risks and beauty. Worpole, Here Comes the Sun, 120.

131

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 26 Aug. 1938.

132

Van Leeuwen, The Springboard in the Pond, 31.

133

Marino, ‘The emergence of municipal baths’, 35–6.

134

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, Star, 31 Oct. 1934.

135

Van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis, 216.

136

Foster, ‘The wilds’, 45.

137

According to Smith, cities wished to design structures, such as swimming baths, that were in keeping with the architecture and scale of their European counterparts. A. Smith, ‘Pool life’, Building, 268 (2003), 16, as quoted in Pussard, ‘Historicising the spaces of leisure’, 180. Also see Pick, ‘The development of baths and pools’, 57.

138

These positive representations only reflected the self-confidence and respectability of Johannesburg's anglophile urban elites. There was little promotional material before the 1920s. The initial image of Johannesburg was that of a coarse and tough mining town. The idea of ‘progress’ – as defined by ‘Britishness’ – was moot as Johannesburg was frequently depicted as a ‘New Babylon’. A concerted effort to change this image occurred in 1925 with the establishment of publicity associations. Bickford-Smith, The Emergence, 13, 14, 132, 158, 171.

139

Robinson, J., ‘Johannesburg's 1936 Empire Exhibition: interaction, segregation and modernity in a South African city’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 29 (2003), 761CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

140

See Bickford-Smith on place-selling, The Emergence, 162.

141

Love, C., ‘State schools, swimming and physical training’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 24 (2007), 665Google Scholar.

142

Myerscough, K., ‘Nymphs, naiads and natation’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 29 (2012), 1914CrossRefGoogle Scholar; C. Parker, ‘The rise of competitive swimming’, 56–7; and Day, D., ‘London swimming professors: Victorian craftsmen and aquatic entrepreneurs’, Sport in History, 30 (2010), 32–54CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

143

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, letter from E.J.L.P., Leader, 26 Nov. 1909.

144

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, Star, 30 Nov. 1937.

145

She was a former Transvaal diving champion as well as a University of the Witwatersrand swimming champion.

146

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, letter from Sue G. Womble, RDM, 29 Sep. 1937.

147

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, RDM, 9 Sep. 1937.

148

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 452, letter from A. Crewe, honorary secretary, Johannesburg Schools’ Amateur Swimming Association, RDM, 7 Oct. 1937.

149

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 26 Dec. 1921; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC file 498, Star, 6 Dec. 1924.

150

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, letter from ‘Swimmer’, Star, 4 Feb. 1919.

151

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 22 Mar. 1919.

152

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, letter from ‘K.T.’, RDM, 21 Jan. 1927.

153

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 498, letter from Harry Melman, Star 6 Dec. 1924. The overcrowding might not have been a surprise as, according to the South African Official Year Book covering the period 1910–25 (UG 8–25), Johannesburg's total white population in 1921 was 151,836. Parnell, ‘Council housing provision’, 16.

154

It should be kept in mind that Johannesburg is land-locked and the summers can be quite hot. There are no large rivers or lakes in which to cool off. The nearest beach is in Durban, 600 kilometres from Johannesburg. Gosseye and Hampson confirmed that the hot climate of Queensland likewise made swimming very popular (J. Gosseye and G. Hampson, ‘“Queensland making a splash”: memorial pools and the body politics of reconstruction’, Queensland Review, 23 (2016), 181). This was not surprising as they share more or less the same latitudinal zone.

155

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, Star, 30 Oct. 1931; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, Star, Nov. 1933.

156

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 30 Aug. 1947.

157

See Batstone for the important role played by swimming clubs to popularize swimming and hence the popularity of the baths. Batstone, ‘Health and recreation’, 190.

158

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 23 Jan. 1909.

159

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 320, RDM, 26 Dec. 1921.

160

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 1 Sep. 1943; and Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 31 Aug. 1944.

161

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 513, RDM, 31 Aug. 1944.

162

Swimming and other aquatic sports became a popular spectator culture. McShane, ‘The past and future of local swimming pools’, 197.

163

Smith, Liquid Assets, 45; Love, ‘Holborn, Lambeth and Manchester’, 636; and Gordon and Inglis, Great Lengths, 60.

164

Katzer, ‘Introduction: sports stadia’, 252.

165

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 27 Jan. 1940.

166

Wits/WCL/HP, AF 1913, JPLPC, file 447, RDM, 27 Jan. 1940.

167

Gordon and Inglis, Great Lengths, 51.

168

Grundlingh, ‘“Parks in the veld”’, 105.

169

- Bale, Sport and Geography, 2nd edn (London, 2003), 4.

170

Doyle, ‘A decade of urban history’, 507.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/urban-history/article/municipal-modernity-the-politics-of-leisure-and-johannesburgs-swimming-baths-1920s-to-1930s/4C3B864BE0DDF1AF2437319219FBD81C#fn55