Champions of South Africa

Olympic champions, Commonwealth Games, World Championships and world record holders.

Boasting 4 swimmers inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame, South Africa is one of the most successful countries in international swimming.

A high point in this history was winning the 4x100m freestyle relay at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games.

1900 - 1960

In 1912 George 'Looper' Godfrey from Natal became the first swimmer to receive Springbok colours when he was selected to represent South Africa at the Helsinki Olympic Games. He swam the 400m freestyle, which was won by George Hodgson - seen in the IOC video below.

The first Olympic medal won by South Africans was the women's 4x100m freestyle relay at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Another Natalian, Oonagh Whitsitt, won the one-ever international medal in the diving competition at the Empire Games in 1930, while Jennie Maakal won bronze at the 1932 Olympic Games.

Joan Harrison won the first South African Olympic swimming gold medal at the Helsinki Games in 1952, and the South African women won another relay medal at Melbourne in 1956.

The era ended with Laura Ranwell setting an Olympic record for the 100-meter backstroke at Rome in 1960, where Natalie Stewart, born in Pretoria but swimming for Great Britain, was awarded the bronze medal, despite her and Laura finishing with the same time of 1:12,0. Natalie set a new world record for the event over 110 yards at the British nationals in Blackpool in September 1960.

1961 - 1991

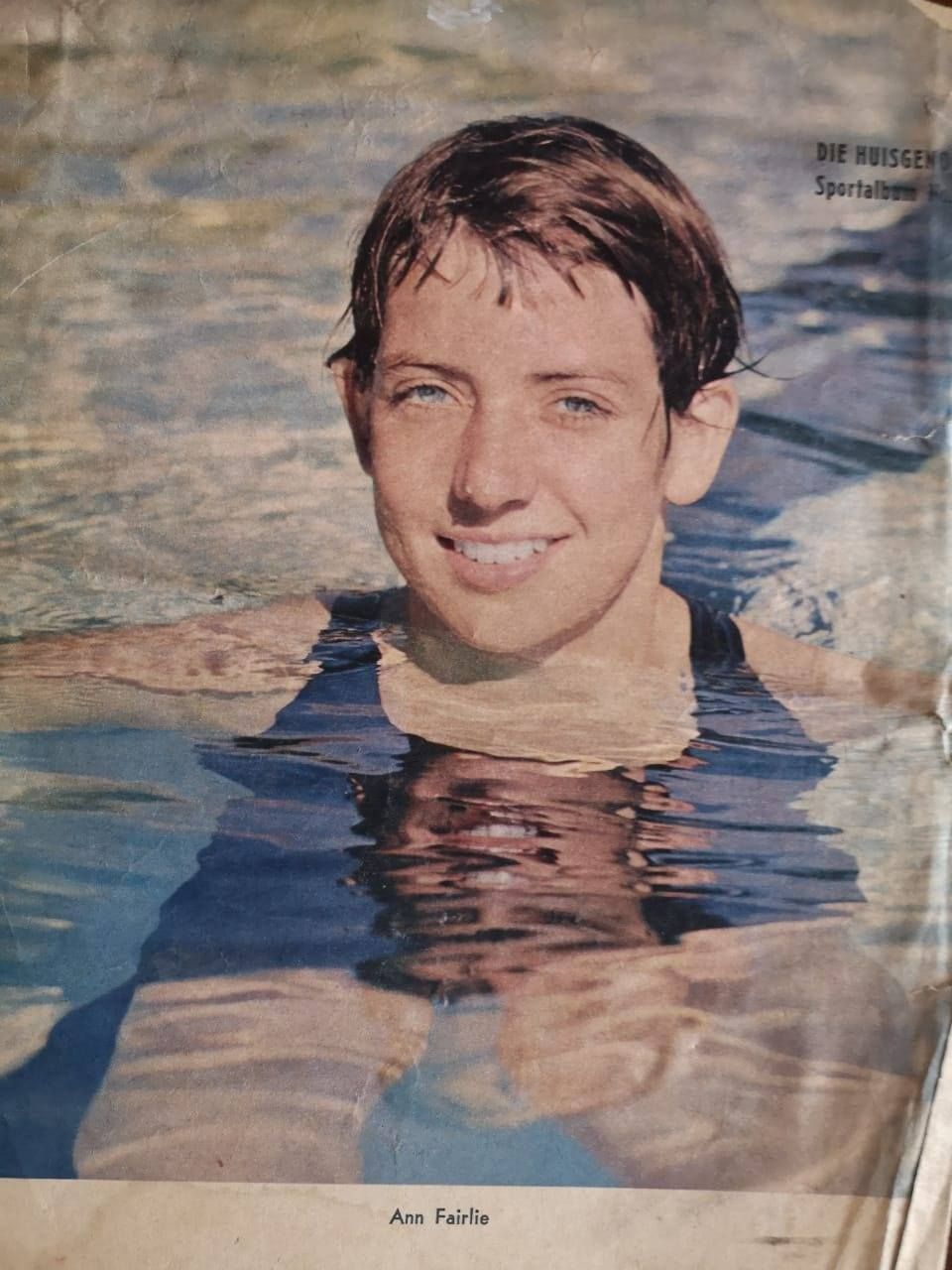

World beaters during the boycott era 1961 - 1991 Despite 30 years of the international sports boycott, South African swimmers continued to set new world records. Karen Muir, Ann Fairlie, Jonty Skinner and Peter Williams all set world records during this period.

1992 -

With the international boycott of South African athletes lifted by in 1991, South African swimmers were again welcomed into international competition. It did not take them long to make an impact.

While the 1992 Olympic Games did not produce any medals, Peter Williams did make a final, finishing 4th, and Marianne Kriel also made a B-Final. Penny Heyns (photo) won double gold in 1996 and was voted World Female Swimmer of the Year in 1996 and 1999.

South Africa won the men's 4x100m freestyle relay at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games in a world record time.

Chad le Clos beat Micheal Phelps in 2012, while Tatyana Schoenmaker won in Toyko in 2021. Matthew Sates and Lara van Niekerk are also in the mix for international honours in 2023.

International Champions

The diaspora of swimmers from South Africa, which began during the 1950's, produced some international champions - including a Princess, a couple of Masters legends, triathletes, coaches, an administrator, and a famous environmentalist.

Commonwealth Games

South Africans heve competed in all but eight of the 22 Commonwealth Games which have been held, from the original Games in 1930 to 1958, and then from 1994 onwards.

Disabled swimmers

In March 1964 the first S.A. Paraplegic Games, organized on a nationwide basis, and with participation from Southern Rhodesia, were held at the Wanderers’ Club in Johannesburg.

Local Champions

The international sports boycott of southern African countries caused many athletes to move overseas and compete at American universities. However - many South African champions chose to stay and be local champions.

Exiles

The first Springbok swimmers won scholarships to the University of Oklahoma in 1953. Since then, the cream of local talent have followed, and while some have returned to compete in their homeland again, the majority never did come back.

Open Water Swimmers

Margaret "Peggy" Duncan swam the English Channel from France on 19 September 1930, being the first South African to do so - and the only person to succeed between 1928 and 1933. Before that, she won the first Robben Island race in 1926, then aged 15, having run away from her convent school in Johannesburg to compete in the event. She was also the first woman to achieve this crossing.