Penny Heyns

14 World records and

World Female Swimmer of the Year - 1996, 1999

World Female Swimmer of the Year - 1996, 1999

During the three decades from 1961 - 1991, when South African swimmers were barred from international competition, South African swimmers failed to maintain the levels set by Karen Muir and Ann Fairlie, with the exceptions of Jonty Skinner and Peter Williams setting world records. In 1992 the re-admission to international competition came as a surprise to all, and the performance of South African swimmers at the Barcelona Olympics was not particularly impressive.

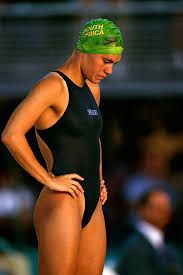

4 Years later it was a different story. Penny Heyns burst on the international swimming scene at the South African Olympic trials at Kings Park in Durban - by setting a world record in the heats of 100m breaststroke. It surprised most of the spectators in Durban, but Penny had already set a new American Open, and NCAA record for the 200-yard breaststroke (2:08.90) earlier that year. She went on to swim in three successive Olympic Games and broke 13 world records in her swimming career.

Click here to see Penny break a world record.

Penelope Heyns, South Africa’s swimming sensation, was born on the 8th of November 1974, in the Eastern Transvaal town of Springs. She started her schooling at Doon Heights Primary and then later attended Amanzimtoti High. She was an excellent school achiever academically and in athletics. In 1987 she became the swim team captain at school and this is when her interest in swimming grew.

In 1992, at the age of 17, she was the youngest member of the South African Olympic team in Barcelona. She did not win any medals but made enough of an impression to be offered a place with a swimming coach in Nebraska, where her coach was Cal Benz. While she was in Nebraska she decided to continue a tertiary education. She joined the University of Nebraska where she later achieved her Degree in Psychology.

She was also a member of the South African squad at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, where she won a bronze medal in the 200 m breaststroke event Heyns continued her swimming career and was asked to represent the USA in the Olympic games but she decided to not let her fellow South Africans down. She even got a tattoo of the Springbok on her shoulder.

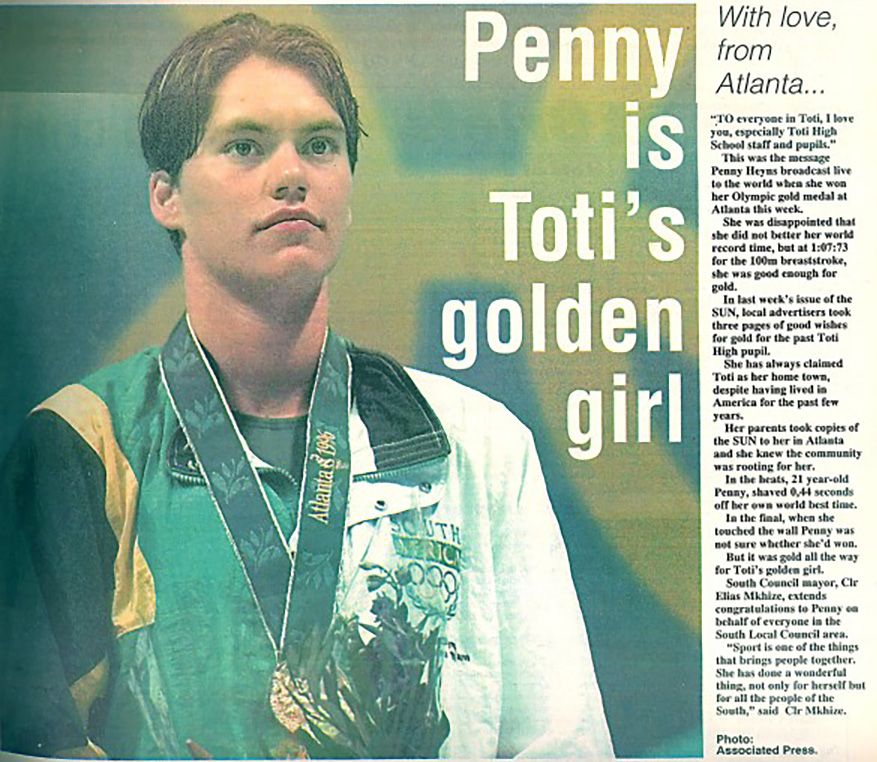

In 1996 she represented South Africa at the Atlanta Olympics. She won both the 100m and 200m breaststroke events and this made her the only woman in the history of the Olympic games to do so.

During the 1998 Goodwill Games in New York, Heyns set the 50 m breaststroke world record, and in 1999, she set eleven world records in three months, swimming at events on three different continents. This made her the simultaneous holder of five out of the possible six breaststroke world records, a feat that had never been achieved before in the history of swimming.

She was named by Swimming World magazine as the Female World Swimmer of the Year in 1996 and 1999. She was also a member of the South African Olympic team at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. She won a bronze medal in the 100 m breaststroke. In the year 2000 Penny announced her retirement from swimming.

Penny has been since traveling giving motivational talks encouraging people not to give up on their dreams.

Check out her website at http://www.pennyheyns.com/

Wêreldrekord vir Heyns

Die Burger 3 Maart 1996

DURBAN. Penny Heyns het gister met 'n blink wêreldrekord in die 100 borsslag slegs World Records geword wat dié prestasie kon behaal. Heyns het reeds in Augustus verlede jaar by die Wêreld Studente Spele in Fukuoka, Japan, gedreig om met die Australiër Samantha Riley se wêreldrekord van 1:07.69 klaar te speel toe sy binne 15 sekondes van dié rekord gedraai het. Maar eintlik wou sy die rekord voor haar tuisskare in Durban verbeter. En gister het sy in die gelaaide atmosfeer voor 'n fanatieke swemskare Riley se rekord met 'n tyd van 1:07.46 verpletter. Heyns was totaal en ingestel op dié rekord. Haar afrigter, Jan Biedeman, het haar uit Nebraska, waar sy die afgelope drie jaar studeer, vergesel om haar in haar aanslag op die rekord by te staan. En die 21-jarige boorling van Amazimtoti in Natal het hom én die skare nie teleurgestel nie. Heyns is slegs die vyfde Suid-Afrikaner om 'n wêreldrekord in die swembad te verbeter.

Ann Fairlie en Karen Muir het die wêreld se rugslag-toneel in die sestigerjare oorheers. Maar politieke isolasie sou weldra sy tol eis. R30000 ryker Vir haar moeite het Heyns R30000 ryker geword, danksy haar borg, Absa. Oor die volgende twaalf maande sal die borg haar elke keer soveel betaal, as sy weer 'n wêreldrekord laat spat. In 1976 het Jonty Skinner die kans ontneem om by die Olimpiese Spele in Montreal 'n aanslag op Olimpiese goud in die 100 vryslag en die wêreldrekord van Jim Montgomery te maak. Montgomery het in Montreal goud gewen en die eerste swemmer geword om die 100 vryslag in minder as 50 sekondes af te lê. Maar net meer as twee weke ná die Spele het Skinner die wêreldrekord in 'n manjifieke 49.44 verpletter.

Dieselfde lot het Peter Williams in 1988 getref. Williams, soos Skinner van die Oos-Kaap, het kort voor die Olimpiese Spele in Seoel die wêreldrekord in die 50 vryslag tot 22.18 verbeter. Die antagonasee jeens Suid-Afrika se apartheidspolitiek het in dié tydperk 'n hoogtepunt bereik en Williems se rekord, is anders as dié van Skinner, nie amptelik erken nie. Suid-Afrika het intussen sy muishond-beeld afgeskud en dis in internasionale waters dat Heyns tot dusver gefloreer het.

Former South African coach Cecil Colwin published an interview with Penny in the January 1997 edition of Swimnews magazine.

AN INTERVIEW WITH PENNY HEYNS

Cecil M. Colwin

"I didn't grow up with a dream about Olympic gold," says Penny Heyns, 1996 Olympic 100 and 200 breaststroke gold medallist.

"It's interesting that different people have asked me if I had dreamt about winning at the Olympics. But, the answer is `no,' because in South Africa we were so isolated all those years, I never thought about the Olympic Games.

"Even in 1992, when I knew there was a chance we would go, I swam that season thinking `Oh, well! I'll just do the best I can, and if South Africa is invited to participate, and I make the team, I'll go! But even Barcelona wasn't the wonderful, overwhelming experience, that it should have been..."

However, despite Penny's lack of an Olympic dream, her life portents were always connected subtly with gold and water.

For instance, the gold in her two Olympic medals could have been mined in the gold-mining town of Springs, where she was born. (Springs is only a few miles east of Johannesburg, the centre of the world's richest gold fields.)

And, when Penny was a year old, her family moved to Amanzimtoti, which, in the Zulu language, means "The Place of Sweet Waters."

"That's quite appropriate," I said to Penny. "The waters have been sweet as far as you are concerned."

"Yes!" said Penny. "Did you know that Dingaan, the Zulu king, gave the site this name, over 150 years ago? Well, this is where the water first called me. I was very, very young, swimming in the sea, and in either our pool or the neighbour's pool. Playing on the sands, and in the rock pools, this was my place. I was a `water baby' I suppose."

"A Stupid Idea"

"When I was seven years old, I told my mother I wanted to race, and swim for the school team. Our neighbour overheard me, and was amused. She told my mother she thought this `a stupid idea.'

"I was only in Class Two, and the school wouldn't let us start swimming until we were in the next class, Standard One, and about eight years old. Nevertheless, I went up to the teacher and asked if I could swim, and I tried out for the team, and made the team. This was my introduction to competitive swimming.

"I think it was around Standard Three that I made the South Coast and Natal Districts team, and then went on to swim in the Natal school trials in order to go to the South African Schools' Championships.

"I was about ten, and until then, I had never swum for a club. I recall always trying to swim a little better in my backyard pool. You know, working on my stroke. My mother's got a good eye for stroke, and she used to help me. She wasn't a swimmer, but I think she just had a talent for teaching."

Early Career

`When I was about twelve or thirteen, I joined the club at Amanzimitoti High School. It consisted of a bunch of parents and teachers who basically just formed their own club."

Penny said that she had no professional coaching until 1988, when Graham du Toit, a former Transvaal swimmer, came to `Toti' (as Amanzimtoti was colloquially called), and he coached her until 1992.

"Graham didn't believe in doing a lot of distance work which, in retrospect, was good for me, because I still feel fairly fresh in terms of swimming and competition. We would go five workouts a week, each one ranging between 3,000 and 3,500 metres, that's all. But in a lot of it, the emphasis was on quality and not quantity. Most of the stuff was all 100% effort work. I think this program served my 100 well, but my 200 suffered. I didn't start seeing results in my 200 breaststroke until after I came to Nebraska.

"In my first nationals in 1989, I came third in the 200, and my second nationals was in Johannesburg in 1990 and I got two silvers in the 100 and the 200, behind Lizelle Peacock, the reigning South African champion."

Beneficial Stroke Changes

"Around 1991, a coach by the name of `Tubby' Lynn came up to me and asked me if I wouldn't give him the chance to look at my stroke and comment on it. He suggested a couple of changes, for instance, using my head more in the forward throw, sort of copying the Barrowman style, but not quite yet, at that stage.

"With just these couple of adjustments, I went on to the nationals in Cape Town in 1991, and broke the South African record in the 100 breaststroke in 1:12.57. This was also where I got my Springbok colours (South African international blazer). I won the 200, and I think I went a 2:40.

"The following year (1992) was the Olympic trials, and in the prelims I went a 1:12.8, and in the finals, I touched behind Sheila Turner. There was a lot of controversy about my being in the team."

"Chase Your Own Dreams"

"I always seemed to find somebody I looked up to, or admired a lot, and initially, it was Julia (Russell). She had been swimming since she was a lot younger. She was my role model. We swam in the same age group."

"And so, all along, even later on in my swimming career, it would have been people like, I suppose most recently, Samantha Riley, because she had broken the world record. So it was always people that I admired and, initially, I wanted to swim and be like them."

Penny said that she later realized that it was important "not to always chase people, because their performances will fluctuate, so rather chase your own goals and dreams.

"Along the way, I learned many lessons, and I suppose these all started when I came to Nebraska in January, '93. I felt my breakthrough, in terms of international competition, would have started with the Commonwealth Games in 1994. That's where I got the bronze medal in the 100 breaststroke."

Asked if she had started to put post-apartheid South Africa on the map with that swim, Penny said "Well, I didn't look at it that way, because I did compete at Barcelona, but I was so young in terms of experience, and I maybe didn't make as much of the opportunity as I should have done.

"But, obviously, when I swam in the Commonwealth Games, I had already had some experience against either international swimmers, or swimmers of a high calibre, through the NCAAs and the American program in general."

More in Control

"When I went to the Commonwealth Games, I was more in control, and had more feasible goals for what I wanted to do, and so, looking at my performances there, I went on to Rome for the World Championships, intending that I possibly could get a medal."

"In the 100 breaststroke, I qualified second going into the final. After that performance, the South African coaches, who were there at the time, said `Oh! You're looking great. Maybe you can win!' I started thinking `Well, maybe I can' but, deep down inside, I knew that I wasn't at that point yet.

"That was a good lesson for me, because I went into the race and, because I so badly wanted to win, I didn't have respect for the other two medals, which would have been better for me, at that stage.

"I dived in, and I swam Samantha's race. I didn't swim my own, and I got sixth place. The girl who got the bronze medal had a time slower than what mine had been in the heats. So, had I swum my own race, I possibly would have had a medal.

"Usually, I would count my strokes, even during a main race, but in Rome, I didn't. I just swam. I went out with Samantha Riley. I tried to stay with her, and then died coming back. Maybe I scrambled through my stroke. I made a lot of mistakes in that race. I didn't swim my own race. I tried to pace it according to everyone else."

At the 1995 Pan Pacs

I told Penny that I had seen her compete against Samantha Riley in the 200 at the 1995 Pan Pacs in Atlanta, and I asked her how she felt about that swim. "Well, I think I knew, going into the Pan Pacs, that the 200, whatever happened, would be a creditable swim, because in our nationals that year, I had gone 2:29 which ranked me first in the world for the season. Of course, my 100 was a much better swim in comparison. I went 1:08.4."

Penny expressed disappointment that Samantha was disqualified in the 100. "I had prepared for the 100 that season, and so, of course, I thought I stood a chance of beating her in the 100, and then she was DQ'd. But, in the 200, I knew that I just wanted to stay as close to her as I could. So I felt that I learned a lot about myself in that race, as well as how to swim the race.

"That 200 was an important race for me; when I came out of it, I knew how much work I needed to do, and where I was in my planning for 1996."

Self-Analysis and "The Perfect Race"

Penny said that she does a lot of thinking about her swimming. After a race, she sits back and analyzes it. "Not to the extent of being tied up with too many little details, but to work out in pretty simple terms, what happened in that race, what I did that was good, what I did that was bad, and where I could learn and improve. I think, every time I race, there's always something I can find, that I can do better."

I questioned Penny closely on this aspect of her swimming. "Do you think you've ever swum a perfect race?"

"No," she said.

"Do you think anybody ever swims a perfect race?"

Quick as a flash, she replied "I think people swim close to perfect. I don't think there's such a thing as perfect, because if you are doing yourself justice, you will always manage to find something you can improve."

I said, "That's a good comment. To be a champion, or a world record holder, you've got to know every tile in the pool. Every stroke you make must have meaning, any stroke that slips the water is a stroke you are not using properly, and it all adds up by the end of the race."

At the Atlanta Olympics

Penny said "That's true. It's a good thing you asked me about a perfect race, because I've often been asked, how come after my swims at the Olympics, didn't I seem that happy?

"Well the reason was that in the 100, I knew that I'd get the record in the morning, although I also expected Amanda Beard and Samantha (Riley) to probably break it in the fifth heat. They were in the fifth heat, and I was in the sixth heat, I think."

"Did that worry you?" I asked.

"No, I expected it," she said. "I was waiting for it to happen. I had the attitude that I would then have to go quicker. Whatever they did, I had to go quicker. I was really surprised when they didn't improve on the time, and I just went out to still swim my best race, and, when I touched I was happy with the time, although I had hoped that when I broke the world record, it would be under 67. Because of that, I thought, well O.K., I can go faster tonight.

"Also, during that race, I remember diving in, and, for the first three or four strokes I didn't feel great. I wasn't on top of the water and I didn't feel as powerful as I would have to liked to have felt. Also, I glided into the turn. So, looking at that record swim, I thought that there was a lot I could still do to improve upon it.

"Unfortunately, in the evening, it wasn't that I was nervous of the other girls. I so badly wanted to go faster, and I just knew that there were things that I could improve to make me swim faster, and it would be ideal if I could do it in the final.

"But, because I was so anxious and eager to break the record again, I rushed my stroke towards the end of my race. Because of this mistake, I came up short at the wall, and that's where that `wonderful' glide came into it. So there are always mistakes..."

Penny said that her 200 race at the Olympics was probably her best ever effort.

"I knew that I could either go out pacing it with Amanda, and then come back and beat her at the end, or I could go out hard, and hang in there. But, I knew that my speed would count in my favour, and so I decided to go out hard. I had to use my speed to benefit my race, and then just try to hang in there."

Streamlining for Speed

Asked what she thought was the strong point in her swimming, Penny said "Mainly my stroke, I think. Apart from that, I think you have to be mentally tough."

Penny Heyns is noted for her unusually straight and streamlined body posture, especially during the underwater phase of her stroke. I asked her to talk about her technique.

"I think that, if you break my stroke up, in the sense of a front and back half, then obviously my kick is my strong point. My kick is a lot stronger than my pull, although, hopefully, my pull is getting stronger every season. But, recently, I was reading an article. I can't remember who wrote it, but the person was saying that the body position is 70% and the arms and legs motion is 30%, and, that's true, because I believe that to be true, not just watching my stroke, but even watching Julia's (Russell) improvement over the last season."

Penny said that female swimmers naturally tend to kick down. "If you work on it, you can kick more directly backward, which is what guys have in their favour. I think it's something to do with their hips. I know that I've been kicking directly backward for a long time. This helps to balance out your body position. And I know Julia's starting to do this now, and I can definitely see an improvement in her stroke."

Noticing that Penny has very long thighs, I asked her "If you were to draw your knees up too much, you would get a lot of resistance. Maybe your natural body build makes you want to keep those thighs streamlined in line with your body, and also to use the strength in those quadriceps muscles?"

"Yes, definitely," she said. "I don't think it's so much strengthwe do a lot of leg workbut it's the efficiency of catching the water. You've got to hold the water, and cut resistance in every way you can."

Mentioning that too many breaststrokers apply too much power in the early part of the kick, I asked Penny to talk about her kick.

"It's difficult to think about it when you're not in the water," she said (demonstrating). "But the way I think about the kick is that, when you bring your feet up, instead of just kicking back, like you would kick-start a motor bike, you want to flex your feet outwards, and almost the whole bottom area of your legs should whip around, rather than just go directly down.

"Without bringing the thigh forward, you want to lift your ankles and the lower part of the legs back. The moment you pike at the hips, and you draw your legs up, then you alter your body position, and then you create resistance. I know they supposedly modelled this after the Barrowman stroke, and the `wave technique.' "

Breaststroke Arm Action

The rest of our conversation on technique went like this:

C: "Now, your arm action; when you start your stroke, and you go into the lateral phase of the pull, what do you do with your hand on the wrist? Do you flex your wrist, or do you keep your hand in line with your forearm?"

P: "Let's just break it down. To start the stroke, you want to keep the palms out, facing outwards. The reason for that is when you start bending your elbows, your elbows will be higher than your hands. A lot of breaststrokers, when they start pulling like this (demonstrates), this happens; the elbows drop."

C: "They get into the `praying mantis' position?"

P: "That's right. So, if you keep the palms of your hands out, that would be the easiest way for one to learn. It's almost like getting your fingers into a crack in the wall, and then you pull yourself through. O.K. So that's the first motion. After that, you want to try and keep your hand and forearm like a paddle. So this is the theory outside the water; I don't know exactly about when you're in the water. Obviously, you've got to get a feel for it, and I think that's where Julia and I are lucky; we tend to have a good feel for our strokes.

"At this point, you start to pitch your hands more downward, and the idea is to then start sculling in, keeping your elbows in front of your chest. And this sculling in motion also lifts your body up, which allows you to breathe. I have the impression that a lot of swimmers are coming up very high, and then going down, and they're causing a lot of resistance.

"What we try to do when we scull in, is to shrug the shoulders and drop the head, almost on the chest. Initially, for breaststrokers trying this stroke, they will feel that their forward vision is somewhat reduced. They can't see, it's a lot more obscure. But when you get stronger, you'll lift up high enough, and you'll still be able to see in front. The lift happens without your making it. If you try to make it happen by using your kick, it will cause you to kick down, and you'll cause a lot of resistance."

C: "A good breaststroke style is like a good butterfly stroke; either it's all right or it's all wrong."

P: "I have the feeling, or the opinion, should I say, that you're either born with a talent for breaststroke or you're not. I mean it's very difficult. You can learn breaststroke, but I don't think you can be a top breaststroker without having a natural talent, a knack for it. It just seems to me that people who are in the top range seem to be more purely breaststrokers, and if they're lucky in that their other strokes are good, they can do I.M. You find people who are freestylers and backstrokers, who tend to be good in the other strokes except breaststroke. The breaststroke swimmer tends to be purely a breaststroker."

C: "Do you ever swim the other strokes?"

P: (Laughs) "Very rarely. I did do the 50 free, and I've done the 200 I.M., but it's only been for college swimming because they needed me. It wasn't something I'd do internationally."

Coach "Tubby" Lynn

I asked Penny to tell me more about "Tubby" Lynn's influence on her swimming.

"I don't know his first name," she said. "Everyone calls him `Tubby,' but he doesn't look tubby. Well, he's definitely had a big influence, and I still keep in contact with him. When I go home, I always go and check my stroke with him. He's been responsible for both my style, and for Julia's (Russell). A lot of the improvements that we've had over the last three years can be attributed to Tubby."

I said "You both have beautiful techniques; very fluent, a pleasure to watch."

Penny said "I think this is due to our background; what we did when we were in South Africa. You know Julia is more accustomed, I think, to the kind of training that we do here, incorporating a lot more, not heavy miles, but distance to the point of doing between 5,000 and 6,000 yards, whereas, before, I used to just do sprints. I never knew what drills were, or anything like that."

Asked her opinion about drills, Penny said "I like them. I think they are necessary, especially my favourite, which is `two kick, one pull.' However, Tubby doesn't really like it much because he thinks you get into a bad habit of dipping too low under the water, and sinking. But I can't do drills slowly. When I do a drill set, I'm just as tired as I would be if I did a normal swimming set. And I think, in order to get the benefit out of the `two-kick, one pull' drill, you have to go hard, otherwise you do tend to sink, and that's going to start spoiling your timing."

Coach Jan Bidrman

Asked about the difference in her training since arriving in Nebraska, and whether she did more distance work, Penny said "It was always a steady increase each season. When I first came to Nebraska, I swam with my coach's wife, Amy Tidball, before they got married. She was a freestyle swimmer. During that season, I got accustomed to swimming a little more distance, but nothing extreme, and just really getting settled in the U.S."

Penny said that when she returned home to South Africa for the summer, she worked out a great deal with Tubby. "I think it was during that period of time that I really caught on to what I was supposed to be doing with my stroke. That was between May and August, 1993.

"So, it was during that summer period that I worked on my stroke and caught on to all Tubby's ideas. When I got back to Nebraska, it was still one semester before Julia would join us. At that stage I was the only female breaststroker on the team.

"There were two other male breaststrokers on the team, and they happened to be European, so they gave those swimmers to Jan (Bidrman). Jan wasn't an official coach at that stage. He was just a grad assistant, in international business, I think. He was studying at the University."

"I had a choice of swimming with Jan, half a season, and the other half with Keith Moore, the sprint coach, and I said to them that I would prefer to swim with one or the other for the whole season. I don't want to chop and change.

"Then I spoke to Jan, and I felt very comfortable with his philosophies about swimming, and I knew that he had a lot of experience as an international swimmer himself. So I felt I had the confidence in him as a coach."

Asked to describe Jan Bidrman's coaching philosophy, Penny said "Well, I think, first of all, Jan isn't just the kind of coach who stands on deck and dictates to you what to do. He taught me how to get to know myself as a swimmer, basically, to be independent of the coach, although still appreciate advice and whatever, which I think is very important. He cares about the swimmers. He's not just a coach, he's a friend.

"The first thing he said to me when we met each other and we decided he would coach me, is that, if I'm willing to give 100%, he'll give a 100%. But it's all up to me. The committment must come from me. He doesn't want me to come to the pool because he's standing there. I must come because it's from me. And I really appreciated that honesty. I knew then, if I put in all the effort, then he would be there for me."

"So, in other words, it would not be a one way trade."

"Yes. It's a two-way relationship, and I really appreciated that honesty. So I started swimming with Jan that season, and we were actually fortunate. It's a pity though for the other two swimmers, but the one was injured, and the other went home for a period of time. So I was the only swimmer swimming with Jan at the time, and that allowed him to really just see what I needed, and get to know me as a swimmer.

"At the same time, I got the work done that I needed to get done. We slowly started setting goals each season, and, every season, Jan believed that I needed to do something different to retain my interest, and also to detect scope for improvement. In so doing, one of the things was to increase the distance.

"Also, by the '94 / '95 season, I started doing breaststroke pulling with paddles. Up until then, I hadn't (used them). This last college season, I worked a lot more with stretch cords, swimming against the resistance. Each season, we've thrown in something as an experiment. It also breaks the monotony, and makes it fun.

"We experimented with introducing new items to the program, but not too much, always still maintaining the control. And, you know, I always feel I have the freedom with Jan to say that, at a certain point of my training, `I'm sorry, maybe I just need a week away from everyone. I'll see you again in a week.' And he trusts me enough to know that I'm only doing it because I believe it's best for me and, if he says to me `O.K. I agree you should do it,' then I know that I'm on the right track."

The University of Nebraska's Media and Recruiting Guide quotes Jan Bidrman's Coaching Philosophy as follows: "Athletes, in co-operation with their coaches, need to form their opinions about training and competition. Only when a coach and an athlete work together can an ultimate goal be accomplished."

A Greater Realization of Self

I suggested to Penny that what Bidrman had helped her to achieve was really a greater realization of self. This came out in everything she said in this interview.

"Yes, that's so," Penny agreed. "I think it's really something he has imparted to us. You know, it's also up to the swimmer though. Julia and I were talking, and it seems that the girls in the squad have always performed better than the guys in the last two seasons, but I think it is just because we have taken what he has given us, and used it."

I comment "A lot of people think that, because you have a coach, you automatically get better. The coach can only tell you what to do, and how to do it, and, in the final criterion, something has to come from the swimmer."

Penny agreed "Definitely, and I think, like you said, sometimes I think that I think too much about my swimming and my stroke, and everything."

"How so?"

"Well, I'm inclined to do so, at this period of my training (early season). It's the worst for me always, because I'm impatient. I want everything to happen now. I know what I need to do in my stroke."

"You don't look impatient!"

"I'm getting more control over it these days, Penny laughed. "But during the last college season, it was like the Devil was chasing me."

"You're not swimming college anymore?"

"No, I'm not," Penny confirmed.

Penny Heyns Going to Calgary?

I had heard a rumour that Penny may come to Canada, and I asked her if that was correct.

"I may. Jan's got the head coach position at Calgary. And, right now, I think the best thing for both him, and the swimmers in the team at Calgary, and for me, is that he goes ahead, until May, on his own. That gives him the opportunity to develop a relationship with the swimmers there, without me being around. And then, Julia may also, I don't know, go up for a while in the summer, but I'm definitely going to go up in the summer for a while, and swim with Jan."

"Will you become affiliated to a Canadian club, or am I going ahead of the piece?" I asked Penny.

"I don't know yet. I'll see what it's like in Calgary. I don't want to just jump into a decision and move. I want to first see what it's like, and then I'll decide. There are a lot of pro's to moving, and there are a couple of things I'm not sure about. For instance, if I move to Canada, I leave behind a very big support base in Lincoln. Jan's biggest concern is that I would leave behind a lot of friends, because there are a lot of South Africans there."

Meets President Nelson Mandela

I asked Penny how important it was for her to represent South Africa in international competition. She said "I think, as I'm growing older, and realizing the privilege of making these international teams, it's becoming more and more important. It really became important to me after I had met President Nelson Mandela. Actually I met him in May '95 briefly at the Presidential Sports Awards, and then this year (in March, 1996). After I had broken the world record, they flew me down, and I met him and spoke to him at a private tea for about half an hour.

"First of all, he shook my hand, and said he'd never wash his hand again. So I said I'd never wash mine! Then he wanted to introduce me to his grandson; that was just a joke, but he indicated that he was very pleased with all the young athletes in the country, and that we were ambassadors, and that it was our responsibility to carry ourselves well in international arenas of sport. Also he told me that he was pleased with the world record, and wished me the best of luck for the Olympic Games, and I said "Well, you know I'm now more inspired to go on, and try and win the gold."

The Aftermath of Victory

Penny commented on the public reaction when she returned to South Africa, having won at the Olympics. "The hype was a bit of a surprise to me. Already, I had got a feel for what it might be like while I was still in Atlanta, because the media went quite wild, and there was this building they called The Pavilion, just outside the village. It was like "South Africa House," and I was forever being asked to be there.

"It was either media, or it was somebody who suddenly decided they would be a great agent for me. That was the most overwhelming thing for me at the time, that people were suddenly talking money, and things that I had never been accustomed to, and people were saying `Strike while the iron's hot,' and `You've got to make these decisions now.' I didn't know which way to turn, and my parents didn't really know either. But, fortunately, I had some people from Nebraska there who helped me and advised me, and it wasn't too bad.

"Because of that hype, I really expected it would be bad when I got home. I really expected the worst, I think, and, when I got there, I just dealt with it, one day at a time. It was wonderful when we arrived at the airport, the whole of Johannesburg International Airport was full of people. The response was great. The people think more the black people's response to our achievements was just wonderful, and we had a ticker tape parade through the streets of Johannesburg on the second day we were back, and then the medal winners also had a bit of a banquet and after that, we were driven to Pretoria where we met President Nelson Mandela.

"It was just amazing. I mean it was something. I can't explain it, even now, after being in America for a month and going back. I thought it would have died down, and it really was a surprise. When I got back home, people were still talking about the Olympics, and, especially about the swim team. I think they realized that the achievements of the swimmers were remarkable. They said, per capita, we did better than any country in the world."

1996. The Penny Heyns springbok tattoo

In the months between breaking the world record in Durban and the Olympics, I had gone to a tattoo parlour with Julia Russell. Many swimmers get tattoos in the build-up to an Olympics. Some choose their country's flag, some their national emblems, some the Olympic rings. They get tattoos over their hearts, on their ankles, on their buttocks. Mine was on my back, along my left shoulder blade. It was after I had been selected for the South African Olympic squad in March 1996 that Julia suggested we both get a commemorative tattoo. I agreed, but with a proviso: my mother had to approve. Secretly, I thought it was a crazy idea and I only brought Mom into the equation because I thought she wouldn't go along with it. I was wrong. "Penny, I think it's a brilliant idea - as long as the tattoo is discreet," Mom said, much to my astonishment.

I didn't think about it again until, back in Nebraska, following the Nationals, Julia again raised the subject. I gave in reluctantly, still not fully convinced. Shortly after arriving in La Grange, I showed my tattoo to reporter Gary Lemke, who was covering the Games for the Independent Newspaper Group. He knew I had been planning on getting one as I had confided in him in Durban. Now he was asking whether I'd actually had the nerve to go through with it. After a press conference, Gary, his photographer colleague and I went behind a building where I revealed my new tattoo. Within hours, my shoulder, with its accompanying image of a Springbok leaping over the Olympic rings, was splashed all over the front pages of the South African newspapers. This was no big deal to me.

I had chosen the Springbok because, for me, it represented the highest honour for a South African sportsperson. And the symbol leaping over the Olympic rings seemed a nice touch. Little was I to know what a controversy it had caused back home. Reports of articles in the South African press were constantly being faxed through to Nocsa and pasted on the notice board in the La Grange Teachers' Training College, where the squad was staying for a fortnight. The Springbok was, and still is, controversial in post-apartheid South Africa. Mom didn't take long to call me. "I saw your tattoo in the paper this morning. Why is it so big, my girl?" It's actually not that big, but I suppose it's not exactly discreet either, easily visible when I'm dressed in my swimsuit. She was not the only one who was concerned. Sam Ramsamy, the Nocsa president, summoned me to his office. For him, the Springbok was a symbol of oppression. He had spent many years, fighting for the anti-apartheid movement. "I believe you have a tattoo," he said. "I hope you're not making a political statement." I wasn't and told him so. "No it's not. It's got nothing to do with politics. I have always been aware of the significance of the Springbok as a sporting symbol; it represents the pinnacle of one's career," I explained. "It has that wow effect on me. In 1991 I was the only female swimmer to get Springbok colours.

Heyns Retires

19 September 2000 - Craig Lord - Swimming World Magazine

PENNY Heyns, the South African who is the only woman ever to win both the 100 and 200 metres Olympic breaststroke titles, announced her retirement from international swimming today after failing to make it through to the semi-finals of the 200 metres breaststroke. Asked if her 20th place finish in 2mins 30.17sec, her slowest time for six years, would mean the end of Penny Heyns, the South African who set 11 world records – long and short-course – from July to September 1999, replied: "It's never the end of Penny Heyns but its my last swim at this level." A deeply religious woman who prays before every race, Heyns added: "God has better things in mind for me."

Born in Springs, Gauteng, in South Africa on November 8, 1974, Heyns's family moved to a town called Amanzimtoti in Kwazulu Natal when she was a year old. The town name means "The place of sweet waters" in Zulu. Between 1996 and 1999, Heyns enjoyed many a sweet moment in the water.

During those years, she won both Olympic titles, and established five world records over 100 metres and four over 200 metres. Within the space of six days at the Pan Pacific Championships at the Sydney Olympic pool in 1999, she broke the 100 metres record once, the 200 metres twice and asked if she could do a time trial over 50 metres – the result, a fourth world record within a week. Those standards still remain, at 30.83sec, 1min 06.52sec and 2mins 23.64sec.

In achieving what she did in such a short space of time, she joined the likes of Americans Debbie Meyer and Mark Spitz in the league of the few who have made such a massive run on the record books.

After winning in Atlanta in 1996 – where she caused controversy by sporting a Springbok tattoo, which many in South Africa regarded as a symbol of apartheid – Heyns was taken aback by the publicity she generated. The tattoo had not meant to be "offensive" she said, while her apparent inability to show any emotion whatsoever as she received her gold medals was explained thus: "I had seen people crying and waving and being overjoyed at winning a medal, but I felt if I were to do that, it would be acting. I didn't know what to do. Being South African, I didn't grow up with the Olympic dream like most people. Only when I went back to South Africa did I realise what a big deal it was."

After Atlanta, Heyns went back to training. But at the world championships in Perth, Australia failed to win a medal. "I had no desire any more," she said. "I was miserable, I had no peace…now and then I'd get into the water…I wasn't lifting weights. People were telling me to quit."

She did not. Instead, she moved to rejoin her former coach Jan Birdman in Calgary, Canada. She started weight-training again, packed on the pounds with the help of creatine, the legal muscle-building substance and by the Pan Pacific Championships in August 1999 was in the shape of her life.

Then in March, this year disaster struck. One of her closest friends, Tara Sloan, one of Canada's most popular swimmers and also a breaststroke specialist, died when her car crashed.

Heyns was with her when she died in hospital and said that the tragedy had "tired me out emotionally".

In a moving tribute to her late friend, Heyns said Sloan had touched and elevated her life. "You can't say it was an excuse (for my slow swims), but it did affect my training for a while, not just for me, but for others on the team. The greatest thing you can say about someone's life is the effect their presence has on the lives of others.

"You could not know Tara and not be touched. She not only affected my life, but she also affected the lives of those around her. Yes, I miss her very much."

Sloan had been driving to see her grandparents' house in Swift Current when the accident happened. It was the weekend her teammates were travelling to the Olympic Trials. Sloan, 20, was sitting out the Trials but had planned to qualify for the Olympics later that summer.

Heyns said today: "You have to move on and just remember the person. It is the effect she has had or the effect anyone has on people's lives that matters. It taught me what is important."

Heyns finished third in the 100 metres breaststroke in Sydney and said that in some ways she had enjoyed the moment more than her winning experiences in Atlanta.

"I can't explain how proud I am," said Heyns, who defines success as "celebrating your talents and achieving your goals." Of her efforts in Sydney, she said: "I am not at my best but I have given my best."

She added: "You never know how you will handle disappointment until it comes your way. And I thank God that he didn't spare me that experience.

She has not, however, just excelled as a sportswoman in the international arena, but has established herself, after her retirement in 2001, as a businesswoman, guest television presenter, coach and sought-after Inspirational speaker. She builds her presentations on her own experiences with real-life examples applicable to the world of business, sport, and life.

Penny Heyns: Proof that perseverance pays off

APRIL 8, 2015

Reading through this interview was such a delight for me. Ruda Landman, of Carte Blanche fame, and Penny Heyns, Olympic gold medallist, are two very noteworthy individuals that I distinctly remember from my childhood days. I was a swimmer for 12 years of my life and the name Penny Heyns was always brought up in one conversation or another when I trained or participated in galas. This open and honest interview is full of humility and determination and has made me appreciate and admire Penny even more so. Whereas I gave up swimming because I truly began to hate it (especially because I just wasn’t improving); Penny persevered and became the first (and only) woman to have won both the 100m and 200m Breaststroke events at the ’96 Atlanta Olympics. Along with Australian champion Leisel Jones, Heyns is regarded as one of the greatest breaststroke swimmers of all time. Read more on Penny’s incredible life story, what she is doing now and why being in the sporting spotlight was extremely difficult for her. – Tracey Ruff

https://www.biznews.com/thought-leaders/2015/04/08/penny-heyns-proof-that-perseverance-pays-off/

Transcript:

R: Hello and welcome to the Change Exchange and I always get my tongue tied around that one, the Change Exchange. Say it quickly and let’s see if you can. Our guest today is Penny Heyns that we still remember as the golden girl of swimming. You’re still the only woman who has ever won the 100 and 200m breaststroke at the Olympics.

P: That’s correct.

R: Quite a thing!

P: I guess it is in hindsight, at the time you’re young and you don’t really realise the enormity of it and I fully expected each subsequent Olympic Games that someone would do that. And strangely enough it hasn’t been done yet.

R: Did you just…when did swimming become the thing in your life. I mean as a child one just does all kinds of sports at school and then how did you grow into that?

P: Well I grew up along the coast. I was born in Springs but we moved down when I was about a year old and if you grow up along the coast you’ve got to know how to swim. So I suspect I learnt around the age of two or three, joined the school team at seven and only really seriously began swimming for a club level at the age of 12. Umm … as my story goes, it’s not because I loved swimming per say – it’s more the fact of recognising that I have talent and feeling a responsibility that to really develop it to its fullest. And it became apparent that swimming was the stronger of all the various sports that I did and so I guess I went from there.

R: And it’s a hard discipline, it’s… you put in hours, and hours and hours?

P: It is and also because it’s lonely. I think the only other discipline that perhaps is even harder would be gymnastics – because of the injuries and stuff like that. But it’s not a team sport and even if you’re a runner you still have that interaction with your teammates, swimming is very lonely. But I like that, I like the sology (sic).

R: What goes on in your head while you’re doing your lengths?

P: Well it really depends. I formed a habit later on while I was in College because I was so home sick. I had to find a way to focus on the here and now, so I started counting my strokes, which you don’t do in free and back because it’s so complicated. But in breaststroke and butterfly, I counted my strokes and what I did there, I focused on the details because ultimately success is really just a reflection of excellence in the details. And I suppose aside from that, sometimes when you are doing the longer distances, you sing some songs or stuff like that (laughs).

R: But it sounds like almost a meditation.

P: In a sense it is. And since I retired – if I think back on my swimming career, initially anyway – the part I really missed was the training, that time alone and the quiet of that.

R: Interesting. But you were very young, only 17 when you left for America?

P: That’s correct.

R: How did that happen?

P: Well, it was the Olympic year in ‘92 when I was in matric; umm it was the first year that South Africa was readmitted into that Olympic fold, it really came as a bit of a shock … I really didn’t believe that we would go, I didn’t grow up with an Olympic dream, because we’d been in isolation for so long. And then some of the scouts, I guess from America, were out at our Olympic trials and offered me a scholarship and, at first, I said no and I found out my coach at the time contacted them and said offer it again and they offered it again. I did not want to go.

R: Why, why?

P: Well, Barcelona was incredibly disappointing for various reasons. I came 33rd and 34th,which I always joke and say it’s close to last place. And so that was the first time in my career I thought it’s a good idea to retire. But as I sat and…

R: And you were 17 (laughs)?

P: I was 17 yes, the only school pupil on the Olympic team as far as I know. And everyone else after swimming went out and enjoyed Barcelona, and I stayed behind wrestling with this idea that I have an opportunity to go to the United States. And I believe we are given talent and the next thing it’s opportunity and what we do with it really determines our destiny. And I didn’t want to go and I always stress this to my audiences, because often we think that when you have a desire for something that means that’s what you are supposed to do. And in my career I find out quite often it’s the opposite, you may not have the desire. That’s why, whatever you do in life, you must have a deeper foundation for why you’re doing it.

R: Why didn’t you want to go?

P: Well Nebraska is in the centre of the United States. It gets down to minus 20 Celsius, with the wind chill factor even colder.

R: And this is a Durban girl.

P: Yes, it’s a Durban girl and you know I always say my first nationals was in Durban and we stayed in a hotel and I was homesick and I saw my parents throughout the day and I was still homesick. So I was not the kind of kid that slept out and visited away from home a lot. So the idea of moving all the way to the States and you know it was very daunting. And plus at that time I really didn’t love swimming too much given that I’d had such a disappointing Olympics.

R: So what … what made you decide that I’m going to take this on?

P: Well, I was quite prayerful about it and just felt that if I don’t go, I’ll always wonder what if and if I don’t go I also can’t tell myself or my Maker that I’ve done the best I could with the opportunity and the ability I had. So I had to give it a go and I kind of thought it would be one semester and I can say ‘been there done that’. But I realised as I went on and finally kind of settled in over there that it is a great opportunity and at times grew to really love the sport.

R: At times?

P: At times (laughs). I think it’s important to stress that, because a lot of people think as long as you love something then you’re supposed to do it and if you don’t, you move on and a lot of extremely talented people in various areas of life are led by their emotion and they never really reach their full potential.

R: So how did you handle that?

P: Crying in my goggles.

R: It’s an incredible change for a young girl growing up there completely by yourself?

P: Yes

R: Your mother didn’t go with you or anything?

P : No, in fact it was a two-day trip and I arrived in Nebraska in Lincoln – it’s a tiny little airport. I arrived at two – three o’clock came, four o’clock came and the airport was empty, then five o’clock and at six o’clock, they remembered I was arriving. So it was very difficult the first semester and there was one other South African girl who’d arrived and some other South African guys, but they were older than me, another generation of swimmers. I really didn’t know them and I always joke that I swam up and down crying in my goggles, which is the truth. There was no Skype or email, I couldn’t just call home. I had to wait for every second Saturday. So I lived from every second Saturday to second Saturday. And that’s why I say, I realised at some point that I’m wasting my time unless I change my mind-set. And that’s where the habit of counting strokes came in, because if I could manage what I am doing in the moment, to stay here and control whatever it is I am doing right now, that’s the only way we can be successful. You know then I’ll be able to be a little happier and as I did that, obviously, I improved in my swimming. And if you improve at whatever you’re doing then you become a little more happier.

R: And then came ‘96 and the famous double victory.

P: Yes.

R: Did you see it coming; did you think it might go to, might happen?

P: Well I guess if someone had told me in Barcelona that you might go to the next Olympics I would have thought they were nuts. Let alone go and swim a final and I never knew that no one had done the double. If I had known, I probably wouldn’t have done it, so ignorance is bliss. Umm … I had set some goals in ‘94. The second time I wanted to retire from swimming at the age of 19 and my mother said “you can retire or you can choose to live with your failures and learn from them and that could be the catapult, the nugget of truth you need to go on to your future successes”. And there I set some goals for the following two years. And that swim-meet at the World Champs, the South African, no the Australian, girl broke the world record and I realised that in two years’ time I could maybe attempt to swim that time, fully thinking that she would continue to break the world record. That led up to our Olympic trials in March of ‘96 and I broke the world record for the first time and obviously going into the Olympics as a world record holder….

R: Go back to that moment. What, what was it like?

P: The foundation was laid pretty solidly for the two years leading up to that, so I knew arriving at the swim-meet that I had the potential to break the world record; I had actually just missed it the year before. And umm, I think because I just didn’t plan on it happening then and I actually found out a few days before the swim that my parents were getting a divorce. So it could have shattered the goals I had, but I believe because the foundation had been laid for so long beforehand that there really wasn’t room for any excuses, which in itself is another very valuable lesson. We always keep that excuse in the back pocket and you won’t reach your potential. The swim itself, the first 50 wasn’t as fast as it should have been and, umm, I still don’t how … but I came back faster than ever before and it was the world record. Great elation, hoped to break it again in the evening but with all the commotion post-world record and the excitement of it, you know swimming is a sport where you need to be relaxed and find a rhythm and if you tense up and try a little bit too hard, you miss, which typically is what happened, for quite a few of my world records until later in my career.

R: And then that day at the ‘96 in Atlanta, ‘96 Olympics in Atlanta. How far apart were the two races, the two finals?

P: I think it was like two days apart. Those days you still swam heats and finals and now you have heat, semi-final and final the following evening. I had visualised that race for three months prior to the Olympics. Knowing that in Barcelona I was so overwhelmed by everything, I knew that going into Atlanta, I can’t allow myself to feel that ‘wow this is the Olympics’. I have to consider it as just another event, same race, same people I’ve swam over, you know, against over the past few years. So I visualised the race, all the details of it over a hundred times, so by the time I actually swam the race, it was the heat of the 100 breaststroke, it was a matter of just let my body do what my mind had already done and it was really a sense of I can’t wait to swim. I expected the other girls would swim faster as well, but it turns out they weren’t as fast as I thought, so I knew going into the final that I am safe – if I swim a 90% race, I could win, and 100%, I could get my record again. It turns out it was only 90%. I made some mistakes in the final.

R: And when you realised the magnitude of this, that you’d been the first women, woman to do this? Umm, can you remember that? Was it all too much?

P: I don’t think I knew til quite a bit later. I know after winning the second gold I kind of knew a little more what to expect on the podium, to take my time walking around because you know they had TVs there and they had ushers rushing you along. Everybody else is prepared and takes their time and I was this good little girl following the ushers around and I really on the first gold medal didn’t enjoy it that much. I just went through the motions. Umm … there’s a South African hospitality area usually at the Olympic Games and post-medal presentations and stuff, we went over there and all the media, it was just a frenzy. I didn’t really know, I just went with the flow and I don’t think South Africa knew what to do with me. So in a sense, we were kind of pioneering the way forward. I was very fortunate that I, not by my own doing, had the right people around me from the very start. One of them being Zelda Van Vuuren, my manager at the time and now business partner. And if you don’t – and this is what I see with the guys today – if you don’t have the right people around you, you’re so young, the fame and relative money, today it’s much more. It really just, it could go to your head. And you’re tugged in every direction and everyone just wants to celebrate it, it could lead to party upon party and I think maybe guys are a little safer than girls but like I say, I was really protected. And I think that allowed me to continue and have longevity in my career, otherwise I think it might have unravelled with ‘96.

R: And the relationship with South Africa. Did you, did you see yourself absolutely as South Africa?

P: Definitely, in ‘98, I kind of went through another one of those blips where I thought I should retire, this time I was serious. So much to the point that Sam Ramsamy said, “maybe you shouldn’t swim the Commonwealth trials, sit out and watch and find out what it’s like not to be competing”. And I did that and decided I’ll continue swimming and ahh, despite what he tried to do in terms of getting me into the team, they sort of had their rules so I couldn’t go to the Commonwealth Games. At the time I was training in Canada and they offered that I could swim for Canada and I don’t know, because we are all Commonwealth, there would have been a way that I could have done that. I turned it down because I felt I was born in South Africa for a reason and if I go that route, I could never turn back.

R: What, what was it like … I mean South Africa was flavour of the decade and we were as a country, we were celebrated and carried on everyone’s emotions and you became one of the personifications of that. Did you at 21, 23 feel that?

P: Umm, in my case, I look back and feel I was very blessed and lucky that the pinnacle of my Olympic career anyway happened in ‘96, post our World Cup successes during the time that Madiba was president, which in itself was just amazing. Umm, because he really took a personal interest in the athlete it wasn’t just the President being informed by his staff, I mean he knew things before some of the people around him in terms of achievements. And Baby Jakes and others had the same stories, we had the same stories. I think that because I was based in the States for so long and the change in the country came, I really didn’t know what to expect. So when we returned home I kind of thought Josiah Thugwane would have the support of African people and maybe I would … there would still be this polarisation and there really wasn’t, it was the whole nation celebrating together and that was just… it was amazing. Umm, I still don’t have the words for it. I’m very grateful like I say for the timing of my career and for the people of South Africa. And I suppose I didn’t see myself as really bearing the flag in that way but in hindsight, as I say, with age you grow to appreciate it.

R: And then you were barely what 25 when you finally decided I’m out of here?

P: Yah, well I had umm 21, with’96 Olympics and sort of post Olympics, I would come back home and it was this great big hype. And I always say in the Jo’burg airport everyone knew who I was and I’d go back to America and no one knew who I was. And I went back to Lincoln Nebraska and I didn’t know who I was … and your identity changes or your sense of identity changes because it’s dictated by the reaction of other people and as athletes, we shouldn’t but we find our identity – or at least at some stage in our career – in our sporting achievements. And now, I had a double gold, a world record, more than I had imagined. My coach, which didn’t make it easy, I had been offered a position in Canada, partially because of the recommendation I had given and they thought I’d follow and I decided not to. Essentially, I was in Nebraska on my own without a coach. They had someone assigned but he wasn’t in the tower at the double Olympics pool and knows what to do … and so I was more the coach and that really didn’t work out well, and I reached a stage in 1998 where I absolutely hated swimming. I would go to the pool and get physically ill and that was just before the Commonwealth trials. Once I had decided and again very prayerfully, to go to Canada and continue my career, I had then decided it would be until 2000. So my decision to retire had nothing to do with performance or anything other than the fact that I felt in my gut that that was my career. My coach at the time said “listen things are changing in the swimming world cup circuit. There’ll be money now, you’ll be a little more professional. Don’t you want to continue?” And I just felt that it was the time to retire. Obviously one wonders.

R: You can’t say why?

P: No, just again because my decision to go was prayerful. You know, I had been in the States by then for almost nine years and I never knew what life outside of swimming was and umm, my ‘99 season was the best of my career. Eleven world records in 11 weeks and I don’t know how it happened. And I was on par to do that and even better in 2000, but then there were some unforeseen circumstances and some I couldn’t control with the passing of a teammate and I was a little too involved in that. And umm…some other decisions I made with regards to training. As you get older you’ve got to adapt your training and I don’t think we did that successfully, so 2000 was one step forward two steps back. It didn’t end the way I would have hoped. And if ‘99 was a reflection, then it should have been another double gold but it wasn’t it was a bronze. I didn’t retire because of that, but I felt at the time that it was the end of the career. Also, the people I admired in the sport and were my peers had sort of reached the age where they were retiring. And those days we were retiring quite early. I only announced my retirement … I think it was March of 2001 … because Sam Ramsamy and others had encouraged me not to and hoped I would change my mind. And umm…my mom passed away very unexpectedly in May of 2001 and when that happened, I realised that this was the right time to retire because had I not, I would have been back in the States or Canada and I wouldn’t have had that last Christmas and few months with her, so everything happens as it should.

R: So how does one make that…it’s such an enormous change. You say your life was swimming and you cut that off and then?

P: Complicated. For many reasons, I mean it wasn’t as simple as I’m just retiring from swimming. You know because I’d been based in the States and Canada to a large degree I escaped the hype of South Africa, the fame, I hate the word but all of that and everything that goes with it. I’m quite a private person despite the fact that I do a lot of public stuff, I think a little bit introverted so I was comfortable and safe in Canada, so I moved back home and the adjustment to retiring from swimming, and the adjusting to returning to South Africa and at that stage there weren’t any other successes in swimming and dealing with the public, just never ever felt comfortable. I think it was probably, a year or two or three ago that I started going out into public on my own cause you don’t know that people are looking at you because you’re looking funny or they recognise you. You know what it’s like. And African people are great and they don’t have inhibitions and they come in and chat and say what they want to say then it’s over and done. And, but especially conservative Afrikaans people because they don’t want to intrude, but at the same time they are still looking and it’s difficult. And I just would hide away rather and, on top of that, you know you hear about all the crime in South Africa and I’m safe over there and coming back here, for about 10 years that was very much top of my awareness. And … umm … of course my mother’s passing. And trying to go into the world of business and the adjustment.

R: What did you do? What did you find to do?

P: At first, everyone would expect you to go, continue in the world of swimming and, at the time, I think every swimmer has his or her struggles with the federation. Sometimes we are wrong and sometimes the federation has their part and I think it’s a bit of both. And so I had enough of swimming, I wanted nothing to do with the sport. And so I tried my hand at property and various other business ventures and I was very fortunate once again Zelda had worked … is an entrepreneur and I was kind of guided. When you come out of the sport that’s individual, you are the boss. And now I go into a business, I have a partner who knows way more than me and I’m still trying to be the boss. So that in itself had its own issues that I had to learn and work through but long story short, by the time I think it was after 2010, I was asked by one of the coaches to get involved with his breaststroke swimmers and coach them and I was back on pool deck and really loved it, and found that for the first time again I had that gut feel. When I swam I went on a gut feel, I knew what I had to do and now again on pool deck I know what to do. And other than that, grew the swim clinics that we now present and camps. A lot of them in South Africa and surprisingly last year a lot of them up in Africa. Part of those countries are the expats. Tanzania and Kenya were more the local teams, umm … Namibia as well. So it’s a nice mix. And then, all along I’ve always been involved in the corporate speaking side, motivational speaking and in addition to that over the last, I think it was about four years we started adding other tools let’s say into the programme, brain-based learning development tools. We do a lot of stuff in the schools with the educators, in the corporate sector as well. I’m loving it. I kind of found out I’m a teacher at heart. And I love to motivate, you can be as tired and as down and whatever and suddenly somehow on the day when you’ve got to deal with teaching people and helping people, there’s a new energy that comes. So I’m loving what I’m doing. I think probably more so than even in my swimming career. I feel more at ease and comfortable in my own skin and feel like I’m in the right place in my life right now. I suppose it also comes with age.

R: And who are the people around you who support you?

P: I think obviously my business partner Zelda, who’s now the big sister. Her whole family, we joke I’m the adopted little one in the family because they are in Pretoria where I live. My father and my two brothers are strong supporters still. There are other people one of them is a past teacher of mine throughout my high school years. My other mother, Louise Lemmer, who’s now the head of Toti, Toti high school. I have people like that who are supporters still. And sadly for my generation, those of us who are still in South Africa, our close friends coming out of school and college and stuff, in my case especially, they are overseas. So you tend to, a lot of our work is over the weekends and so umm…it becomes a little bit isolated in that sense.

R: Hard to keep up the connection?

P: Yah, you kind of find this question of ‘what are you doing now?’ and trying to catch up after however many years awkward.

R: Yes! And you say you live in Pretoria now, are you, what’s your home like?

P: Ok, I kind of decided about three years ago that given the travel, having a home and the schlep of the responsibility was too much, so I sold and then opted to rent and lock up and go … and then an opportunity came about to build with a whole bunch of other people on a farm outside of Pretoria and I thought why not, you know, I need a washing machine, that’s about it. And you know for, I grew up in a home with animals and then going to the States and living in Pretoria for over 10 years, it’s almost been for 18 years that I wasn’t able to have any animals and now being on a farm, there’s 12 dogs! (laughs). They keep me busy, I’m tired! But it doesn’t just belong to me. I can come and go as I please, and I like the bush, I like to escape in nature and have my own time.

R: And what makes your space yours? Do you have something special that you take with you?

P: You mean when I travel?

R: No, into your new home, is there a special couch?

P: No

R: No?

P: No, a lot of stuff is still in storage. And I think I got used to when I was overseas to be quite minimalistic, because you know you travel a lot so I tend to carry that over. I suppose a bed is always important, you keep the same bed, the comfortable mattress. Umm, I just think moving now to an environment where I have more space, the bushveld, the farm and the animals, that’s home.

R: All of the very best. I hope it is a very good year for you.

P: Thank you, I am sure it will be, to you too.

R: Thank you.

P: Thanks.

Back in Dar es Salaam for another #PHSwimCamp Kicking off day1 with Breaststroke.

Training von Penny Heyns

https://gsv-schwimmen.de/ratgeber/training/training-von-penny-heyns

Penny Heyns had one of the most remarkable swimming seasons ever last year, breaking world records in the 50, 100 and 200-meter breaststrokes on 11 different occasions! Her coach, Jan Birdman, shares how he trained Penny from May 1998 through her memorable summer of 1999.

After the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, I moved to Calgary while Penny stayed in Nebraska. At the 1998 World Championships in Perth, Penny finished a disappointing fourth in the 100 meter breaststroke. After the meet, she struggled with motivation and was determined to retire from swimming. We talked, and she decided to give swimming one more shot and moved to Calgary. Penny joined the University of Calgary National Swimming Centre and University of Calgary Swim Club in May 1998.

1998 Summer Season

After she moved to Calgary, we spent a few hours talking about her swimming, then set a goal for the 1998 summer. The goal was to swim her fastest 100 meter breaststroke since Atlanta at the 1998 Goodwill Games. The goal was very reasonable. Another goal was for Penny to adjust to her new training environment and a different program.

Mike Blondal, head coach of the University of Calgary, and I are responsible for about 25 swimmers. We work with heart rate monitors, and our training intensities are based on heartbeats per minute.

Working with Penny prior to the Olympics and looking back at her training program, most of the swimming was done at or above anaerobic threshold. She rarely completed a full cycle without being broken down. Too much swimming at medium intensity (anaerobic threshold) was probably the reason why she was getting tired and overtrained. High-intensity swimming such as lactate tolerance and MVO2 was not the issue. The problem was too much ÒeasyÓ swimming at a high intensity.

Dr. David Smith, exercise physiologist at the University of Calgary, helps with monitoring our training program. Most of the meters are swum at a low aerobic level. It is something that I thought I had been doing all along, but I was not.

According to Dr. Smith, low intensity aerobic swimming should be done at the level of 50 beats below the swimmer's maximum heart rate. Swimming at this level develops the aerobic system, but allows the swimmer to recover and prepare for sets where high intensity and high heart rates are required.

Dr. Smith was involved in the preparation of Olympic medal swimmers Mark Tewksbury and Curtis Myden. I figured that I would give slower swimming a shot.

The next challenge was to persuade Penny that easing off was the way to go. Penny's max heart rate is 200 beats per minute. Penny values hard work above anything else-if she were not reminded, her heart rate would be 170 beats per minute and above all the time.

She still struggles a bit with the whole idea, but throughout the summer she started to swim slower on the slow aerobic sets. The main sets were fast, which indicated that her specific fitness was improving. She completed the training cycle without being tired, not overtrained. Also, her in-season meet performances and training performances were steadily improving.

I had not seen Penny working out for almost two years. Not having seen her for a long time, I noticed that she was not as smooth in her stroke as she used to be. She was taking fewer strokes per length, but watching her from a distance, I could see a hesitation in her stroke.

Penny's favorite drills are 2 kick/1 pull and pulling breaststroke with paddles. She had stopped doing these drills after the Olympics, and we decided to include these drills in the training program. In the beginning of the summer, Penny was barely able to do the 2 kick/1 pull drill for 50 meters under 40 seconds. Before the Olympic final, she went 33.8. Breast pull with a dolphin kick, if done right, is very demanding.

Prior to Atlanta, she had done sets of 200s. That summer, Penny struggled with distances over 50 meters. We did some video filming, and as Penny became more fit, her stroke began to improve.

Penny has always worked very hard in the weight room. Bill Makki, the University of Calgary National Sport Centre weight coach, developed a program that combined muscle endurance and explosiveness. That program was somewhat different for Penny-it did not take as much time, but it worked well.

At the Goodwill Games, Penny went 1:08-low twice in the 100 meter breaststroke and a 2:26-high in the 200. Both of these times were Penny's fastest performances since Atlanta. As a bonus, she broke a world record in the 50 meter breaststroke on the way to one of her 100 wins.

Penny was not allowed to compete at the 1998 Commonwealth Games, and she finished her season swimming a few short course meters meets in South Africa. She was very pleased with her performances. Summer goals were accomplished, and she enjoyed swimming. Penny completed the whole summer with a very consistent period of training. The training environment in Calgary was working well.

1998-99 Winter Season

The season started in the middle of October. The winter season finished with the Short Course World Championships and the South African Nationals in April of 1999. The summer season started after that and finished with the 1999 Pan Pacific Games in Sydney. In the beginning of the season, Penny said that she would like to win the Short Course World Championships. Also, she boldly said that at the 1999 Pan Pacific Championships, she would like to break the 200 meter breaststroke world record. I think that she felt that her 100 meter breaststroke world record was a bit out of reach. Most of Penny's main sets are done in 50 meter repeats. She feels that she needs to take breaks to be able to swim with a proper stroke. Penny's 2 kick/1 pull drill is always done at high intensity. That is the only way she can feel her stroke correctly. Following are some of the sets she swam:

- 3 x (10 x 50) on 1:00; after each set, about 400 easy. Her best set was done in December of 1998.

- Set: Odd: 50 drill, 2 kick/1 pull holding 37-38. Even: 50-25 2 kick/1 pull and 25 easy.

- Set: Breaststroke (best set holding 35-high to 36.5 at 18 to 19 strokes per 50 with a heart rate above 190 beats per minute).

- Set: Odd: easy choice. Even: breaststroke fast (best set 34-high at 23 to 24 strokes per 50).

- Breaststroke pull sets are usually 600 meters in length and mostly in 50 meter distances. These sets were done three times a week.

- Race pace 50s: a typical set

24 x 50 on 1:00, done as 8 x 3

2: easy choice

1: 2nd 50 of the 100 minus 1 second (about xx sec.)

- Breaststroke 2 kick/1 pull done at fast pace. At this time, Penny could go 36 seconds per 50 any time. It was a big improvement from the summer.

- 10 x 50 breaststroke on 3:00. In March in short course meters, Penny averaged 32.3.

Most of these sets indicated that she was getting as fast as she had been in 1996.

In the weight room, Penny started doing Olympic lifting three times a week to improve her strength. Twice a week, she did a core strength program using physio balls and wobble boards. Her dryland and weight program took about five hours every week.

Penny and Joanne Malar wanted to go to Australia and Europe for the World Cup meets. Penny was always a better long course swimmer than short course. At these meets, however, she raced really well. Her 50 was consistent at 31-low to -mid, and her 100 meter breaststroke was always 1:07. She did not swim the 200 meter breaststroke at these meets, but she knew that she had done enough work to have a good one.

At the Canadian Nationals in a long course pool in the middle of March, Penny swam her best in-season performances. She went 1:09.3 in the 100 meter breaststroke and 2:28 in the 200 meter breaststroke.

Almost immediately following nationals, Penny traveled to Hong Kong for the Short Course World Championships. She finished in second place three times, swimming her best short course times. However, the results were not as good as expected. She later realized that she had let the issue of prize money interfere with her racing. For Penny, swimming fast is a joy in itself.

After the World Championships, Penny went to South Africa to swim in the South African long course nationals. She swam the 100 meter breaststroke in 1:08.0, which was again a bit faster than the times from the summer before. In the 200 meter breaststroke, she went 2:25.9, which was only a half-second off her best time and a bit more than a second off the world record.

She described the race as ÒglidingÓ for 150 meters and working the last 50. The last 50 was 37-low. She said that during the last 50 meters, she was thinking about the 10 x 50 breaststroke set on 1:00 that she had done before.

After the meets, I spent time looking at the tapes of Penny's races and her stroke analysis. I realized that since the 1995 season, her stroke rate declined every year. For example, at the 1995 Pan Pacific Championships, her stroke rate was between 54 to 56 strokes per minute. At the Olympics, her average stroke rate was about 51, and she did 22 strokes in the first 50 meters and 27 strokes in the second 50 meters. Now, when she was racing, her stroke rate in long course rarely got over 45 strokes per minute. Her stroke counts were about 20 and 24.

1999 Summer Season