Jane Figueiredo

Jane Figueiredo

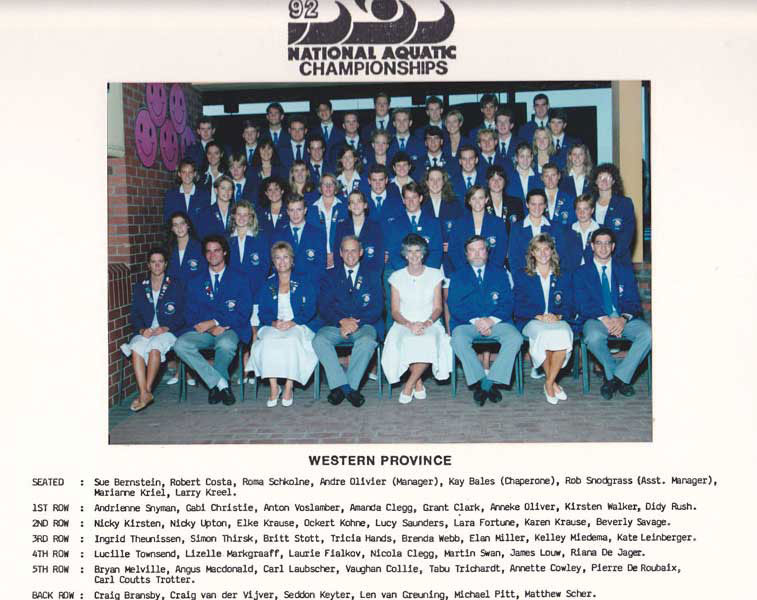

Jane Figueiredo is best known for coaching 2020 Tokyo Olympics men's 10 m synchro champions Tom Daley and Matty Lee, and the 2000 Sydney Olympics women's 3 m springboard champions Vera Ilyina and Yulia Pakhalina.

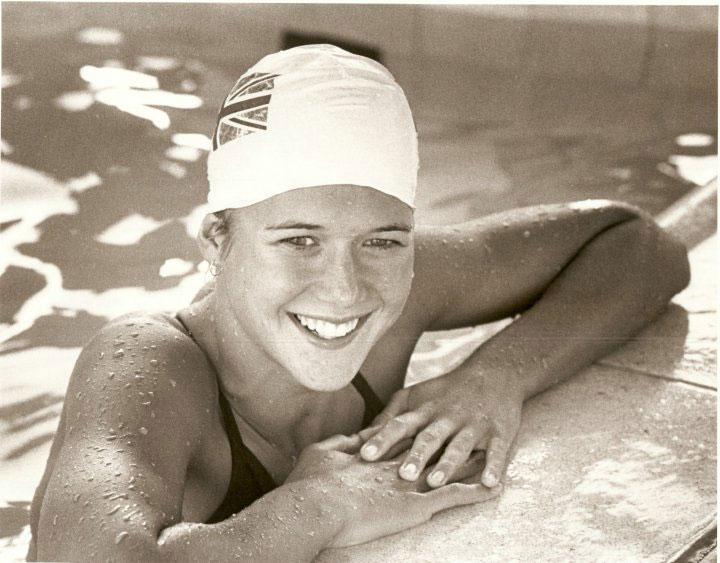

Jane was born in Salisbury, the capital of Rhodesia in December 1963, to a Portuguese father and a British mother, when Rhodesian diving was experiencing a golden era of local dominance. Hers was a very sporting family, and her father was a motor racing driver on the local southern African circuit in the 1960s and '70s. As a child, she was a competitive swimmer, but she found this "boring" so she decided to switch to diving.

Following in the footsteps of a number of other Rhodesian divers like Debbie Hill, Antoinette Wilken and David Parrington, she moved to the University of Houston (UH) in the early 1980s to join their established diving program.

Figueiredo represented Zimbabwe at the 1982 World Aquatics Championships in Ecuador, where she finished in 21st position in the women's 3 m springboard competition. However, for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics she decided to switch allegiance to Portugal – she had Portuguese citizenship through her father – as she had lost touch with the Zimbabwean Aquatic Federation. Figueiredo competed in the 3 m springboard competition but was eliminated after the preliminary round and finished in 22nd position. She went on to represent Portugal again in the 1986 World Aquatics Championships in Spain, where she again competed in the women's 3 m springboard, finishing 23rd.

Figueiredo graduated from UH in 1987, with a BA in Hotel and Restaurant Management. In 1988 she became an assistant diving coach at Houston, and in 1990, she was promoted to head coach for the Houston Cougars diving team, a position that she was to hold until 2014. During her tenure at UH, she was awarded the NCAA Diving Coach of the Year four times, and members of her team won a total of 51 CSCAA All-America honours and eight NCAA championships

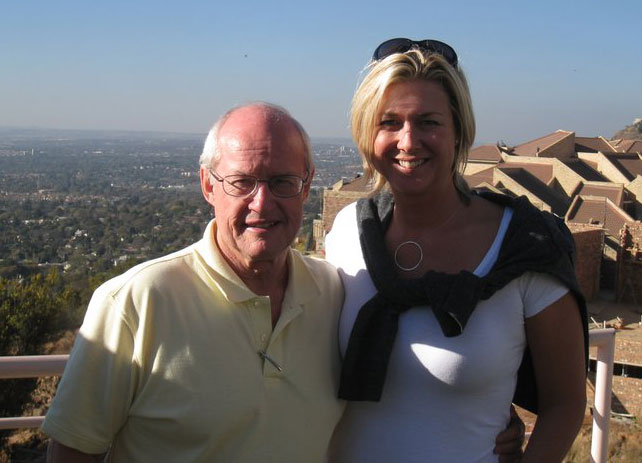

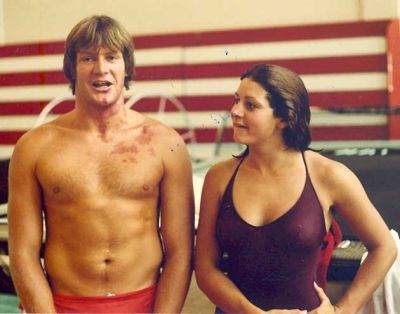

Jane Figueiredo and Dave Parrington after her 2nd place finish on 1 meter at 1985 NCAAs

In October 2013, Figueiredo was approached by British Diving's performance director, Alexei Evangulov, to invite her go to London to give a presentation to the British diving team. During that visit she met with British diving prodigy, Tom Daley, who at the time was planning to move to London from his native Plymouth, and was looking for a new coach.

He offered Figueiredo the job, and visited her in Houston later in 2013 to discuss the move further. At that time, Daley had already won a bronze medal at the 2012 London Olympic Games, but Figueiredo saw that he had greater potential. Figueiredo moved to London and started working with Daley in January 2014. Since that time, Daley and his synchro partners – Daniel Goodfellow, Matty Lee, and Noah Williams – have won bronze at the 2016 Rio Olympics, the gold medal at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and silver at the 2024 Paris Olympics, respectively, all under the guidance of Figueiredo

Figuring it out

20 August 2020

In the next of our Women In Water series, Jane Figueiredo talks us through her experiences in the aquatics world, and a career journey that's spanned multiple continents.

When it comes to Women in Water, few can claim to have had as much influence on their sport as Jane Figueiredo can.

Olympic diver turned multi-medal winning coach, Jane has been a key part of British Diving’s success story over the last six years. But her own personal journey started long before that, so we caught up with her for a two part feature interview to find out more about it.

So just how did a young girl from Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, come to have such an impact on the aquatics world?

“I was a swimmer first” says Jane. “But then that was kind of boring - no disrespect to all the swimmers out there! But for my mind-set, I did a lot of activities; athletics, hockey, swimming, diving, go-karting. My family was very much a sporting family - my dad was a racing car driver.

“I don't remember exactly the day I decided, but I was a swimmer and then I just wasn't really enjoying that and asked my mum to look into diving. There was a gentleman by the name of Clive Mandy who was doing diving in my area. So we started doing trampoline stuff with him in the winters - the pools are closed as it's too cold in your summer, our winter.

“So I started there, and then the diving community in Rhodesia at that time was incredible. We had a slew of amazing divers who were all competing internationally, already going to the Olympic Games. We had an incredible culture of diving, so being in that environment encouraged us to try to get better.”

After her talent became apparent, Jane followed in the footsteps of a number of her compatriots, heading across the Atlantic.

“We had an athlete, a woman by the name of Debbie Hill, who was recruited to the States, the University of Houston. That just started this snowball effect - she went, then she recruited a guy who went, then he recruited another girl and she went, and then I was recruited. I was the fourth person on that list.

David Parrington and Debbie Hill - Rhodesian divers at the University of Houston, 1979.

“So I also went to the Uni of Houston. And then I recruited another guy, my best friend from diving in Zim [Zimbabwe], and he came to Houston. That's how we all ended up in Houston. Then we also had other divers who went to Arizona; in fact we had divers who went all over the States.

“So the culture of diving was just flourishing, but with the departure of the majority of those divers, the quality of diving in Zimbabwe started to deteriorate. Coaches retired as well, so there wasn't really an abundance of divers. We did have a guy, Evan Stewart, who was a very young World Champion; he won the World Champs at a very young age from the 1m Springboard. But once all the good kids left, diving just died a slow death. They tried to keep it going, but then pools started to deteriorate and then once everybody moved to the States and/or South Africa, that was pretty much the end of the sport, to be honest. We still had divers, but it wasn't like it was in the 60s, 70s, 80s.”

Fast forward a few years and Figueiredo’s fulfilled her dream, but possibly not how she or anyone else would have envisioned.

“I dove for Portugal in the 1984 Olympics – it wasn’t Zimbabwe, I dove for Portugal. The reason that came about was because my dad was Portuguese, and I was now living in the States and had a Portuguese passport. We reached out because I wasn't going to be moving back to Zimbabwe, because my parents had moved from Zim to South Africa, so we lost pretty much all contact with the Zim federation. So we reached out to the Portuguese Federation, and they were just amazing. They knew my story, my history. I went and competed at several comps in order to qualify, and they picked me and I dove for Portugal at the 1984 Games in LA. That began my Olympic journey.”

Four years later the now Olympian started her coaching career after some time away from the water.

“I started coaching in late 1988, for the Uni of Houston. I was working full-time, and the coach was leaving to go to the Uni of Tennessee, and he asked me if I'd like to start coaching at the Uni of Houston.

“I was like, 'yeah, okay, but I've already got a full-time job!' So I did both. What I would do is I'd go to work at 6.30am in the morning and then leave by about 3pm, race over to Houston and then coach until about 9pm at night, because I had the college team and the age-group team - the only way I could survive money-wise was to keep this age-group programme going.”

Then came Jane’s first foray into British diving.

“A couple of years in I recruited my first British diver, Olivia Clark. Olivia came to me in the early 1990s from Cheltenham. She was my very first foreign recruit and was fantastic. We had a great few years but in 1996 she didn't qualify for the British Olympic team; they didn't send any women springboard divers because she didn't make the score, although she won the trials. In those days, you had to have a score, and she was one or two points shy of that score.

“I'd gone to many, many meets with her as part of the GB team but as she wasn't picked I was asked to judge the Olympic trials for the US, and it was whilst I was there that I got a phone call from David Sparkes, who I knew because I'd been to several international meets with the British team.

“He called and he said: 'Hey Jane, it's David Sparkes - I'm calling you to ask if you'd be interested in being our Olympic coach for British Diving at the 1996 Olympic Games'.

“I was like: 'What? But my girl didn't even qualify - or are you putting her on the team?!'

“He said: 'No, no, there's something that's happened in the UK, to our Olympic coach - would you be interested, as a neutral party, to coach the GB Olympic team?'

“Obviously I knew all the divers on the team, so I said: 'I'll only consider it under one condition. I need to call all of them and ask them if this is something they want. Otherwise if they don't want it, then I'm not interested.'

“So we went through that process, spoke to Leon (Taylor), Hayley Allen, Tony Alley, Robert Morgan and Lesley Ward. So that was the group, they came back that they wanted me to coach them and that's how that came about!

“That was a situation that nobody wants to be in but it was a great opportunity to help those athletes do something at the Olympic Games, so I ended up doing a training camp with them in June, which was our first time getting together, and then went to the Games in July. So we only had two weeks of training together! It was a ridiculous situation, but it was one we were in and we just had to put our foot to the pedal and try to do the best we could - and those guys were just amazing. It was my first Olympic experience as a coach and one I'll never, ever forget.”

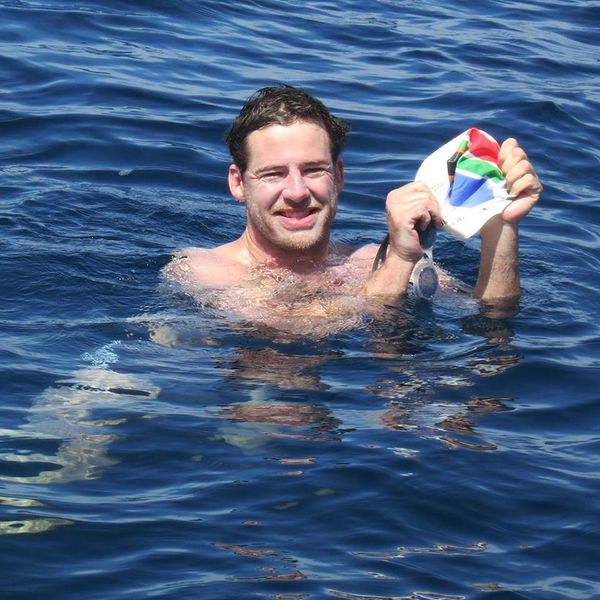

Russian diver Yulia Pakhalina, left, with synchro parter Anastasia Pozdniakova, has a chance to add a pair of medals to the ones she won at the 2000 and 2004 Olympics.

The next chapter of Figueiredo’s career saw her working with the Russian team with great success across four Olympiads, spanning 2000 to 2012.

Then came her move to Britain…

“I moved to London in January of 2014. Tom Daley came to Houston for the first time in September 2013, and I moved to London the following January. I was pulled and dragged and eventually relinquished!

“On a serious note, he is just this very special person, and I mean that. I always say he's a special person first, because the diving was secondary for me. I would say that making the decision to come and coach Tom was first of all because of the way he made me feel when he came to see me, visit me and train with me.

“Coaches always talk about how you're only going to get so many athletes in your whole career and you're going to be very lucky to have those, and they may never come around again. Then comes along Tom Daley. Although he was a bronze medallist in London, and very worthy of that, there was just so much more I could see in him that we could develop, and shoot for a gold medal.

“It was going to take everything, pure sacrifice, which is what I talked about. First of all, he drew me in because of who he is and his enthusiasm. Then, of course, his passion and enthusiasm for the sport of diving, in that order. It was never, 'wow, I'm going to get coach a great diver' - it's never about that. You don't pick them, they pick you!”

Under Jane’s guidance, Daley continued to flourish and it wasn’t too long before Dive London was in the pipeline.

“Tom has a lot to do with that, because first and foremost, we needed other divers, as much as it was phenomenal that we got to spend a year together, just him and I, really one-on-one.

“It was probably a lot harder for him than it was for me, because I relished the opportunity just to have this one-on-one time and to really get to know him and him to know me. I figured we were never going to have that opportunity again, because once that first year passed, we were looking for people to come in and actually be teammates for Tom.”

From there things slowly picked up pace, and post-Rio the club started to thrive, with Grace Reid, Matty Lee and Robyn Birch also looking to Jane to take their careers to the next level.

“We now have a group of four amazing human beings who really commit and dedicate and do what it takes.”

Daley, Figueiredo and Reid at the London 2019 Fina Diving World Series

And with a woman who has experienced many different cultures and coaching styles, you’d struggle to find a better teacher.

“Obviously going from an American culture to a British culture, you have to deal with so many different kinds of cultural things! The American culture is quite fast, they get things done, it's quick, it's snappy, it's pushy, and it's the way sport works in that country. You snooze, you lose. If you're not continuously succeeding, you're done.

“My mum is British, but she grew up and lived her whole life in Africa, so even though she's British I wouldn't say she's British in a cultural sense. Then going from that to a Russian culture which is just so different – I probably learnt a lot of my discipline and passion and forth righteousness, just being able to make decisions quickly, through the Russian system.

“I was thrust into that environment at a very young age, 28 or 29. It was amazing. I've got nothing but complete respect for everything that I gained from that system, with Alexei. Keep in mind, I was coaching in the US with his Russian divers, so there was a lot of pressure on us and me to deliver an incredible quality of diver who was not already made, but at least 60 or 70 percent of the way there, and my job was going to be to take them the extra 30 per cent. If you know much about the sport, that extra 30 per cent is all about the details, and having fun and trying to enjoy the process with a lot of pressure, because they were top three in the world, every one of their divers.

“I didn't know a lot, I didn't think, as a coach when I started coaching them - and then of course learned probably everything I needed to know at that time by coaching them and being in their system, being in Russia, staying there for weeks on end and being immersed into that culture where nobody speaks English.

“It was a very lonely time as a coach because I didn't really have anybody to bounce things off and say 'hey, how you guys doing?' That was a different environment but I wouldn't trade it for the world. Out of that experience, we got a lot of medals, and of course, the passion to always succeed, and if you're not doing it to win, why are you doing it? That was their motto.

“I didn't know anything different, because they were winners, and they did everything, sacrificed everything. That’s unlike what we preach today, which is about having good balance, and that's fantastic too, and those are the times we live in today. But to truly be a winner, I think the ultimate sacrifice is everything - especially when you are looking at a gold medal.

“If I had to look at all the past gold medals in the sport of diving, one thing that definitely stands out is complete sacrifice - and possibly at a detriment to everybody.”

So with such a wealth of experience, it is perhaps surprising that Figueiredo goes right back to day one when asked who her role models are.

“My two coaches in Zim, who were Ron Wood and Adrian Wilson, particularly them because we were diving seven days a week, even on Christmas Day. Those people are still very, very important in my life and, to this day, teach me life lessons as well as coaching lessons.

“Then, of course, my couple of coaches in Houston who were also significant in my coaching career, as well as the likes of my mum, who is such a strong woman, and I think I'm more like than her than anybody. I was just telling Adrian today that my mother is like a rock. Everything I learned, a lot of the qualities of a coach that I am today are from her; resilience, it's going to be okay, just keep going.

“Then it's just my divers - they are really my source of inspiration. That's not one easy answer, but they are all instrumental in different aspects of my life, and I'd be remiss to not mention all of them!”

Many people still make a big deal of females coaching male sporting stars. Mel Marshall and Adam Peaty is an obvious one, as well as Jane and Tom.

“I've had people who've come to the pool and interviewed me and said, 'do you feel as a woman coach that you're a minority?'. I say, 'I never looked at it like that, because I never believe you should be using that as a crutch'. I think women coaches and the male coaches of the world encourage the women coaches. I have always been nothing but encouraged and been supported, 'go get it Jane', even coaching a guy like Tom Daley - people say, 'you must be one of very few women that coaches a man'.

“I'm sure Mel [Marshall] gets the same question. I'm sure she gets bombarded with those sorts of questions. As a strong, passionate, female coach, we don't see it like that. We see it as, 'I've got the tools, I'm good enough, therefore if somebody, a man or a woman comes knocking on my door, that's not something I actually notice’. In Russia, the majority of coaches are women, and they all coach the top male athletes.

“So being Tom Daley's coach and being a woman, that's not something I even think about. It's certainly not something I fall back on if I want to find an excuse for anything. Britain’s Artistic Swimming coach, Paola Basso, has reached out to me before - but not about being a female coach, just about how to motivate her athletes, what do I do in certain circumstances to get a better outcome? So when we are talking to each other, it's more about what is your experience and how can I get a better outcome from my athletes?

“For me as a female coach, in the sport of diving, we have a vast number of women coaches in the sport, a vast amount. So I don't think there's anything that has held them back, which is absolutely fantastic.”

So what about the importance of driving more diversity in aquatics sports across the board, and in the world in general?

“That's just an awesome question, because you just made me think of something in particular.

“It's not what you're faced with - it's how you respond and how you react.

“I think in any culture, and when I think about my American culture, my British culture, my Russian culture and whatever other culture transpires in the future, I will not look to react, I will look to respond in the most positive way I can. That's something we should really be looking at, as opposed to worrying about whose life matters. I think we are all in agreement that everybody's life matters.

“But as far as race, religion or culture, I would just prefer to say that the way you respond is much more indicative of who you are, than the way you react. So if I'm going to teach my kids anything, it's responding in a positive manner that makes any culture, any race, any religion feel comfortable in your presence.

“That's all we can do, because I can't change all the wrongs of the world. Keep in mind that I grew up in a country with a lot of wrongs. But we don't go around advertising that fact. What we do is try to just make it better wherever we are.

“If I'm going to teach my young divers or athletes in any sport or life a skill, it's going to be that. It's what you do with it that matters. It doesn't matter if it's a yellow, green, black, white, red life. Just be kind, be courteous, and that's it, because everybody's different.”

https://www.britishswimming.org/news/diving-news/figueiredo-discusses-diversity-and-dive-london/

Borrow Street pool in Bulawayo

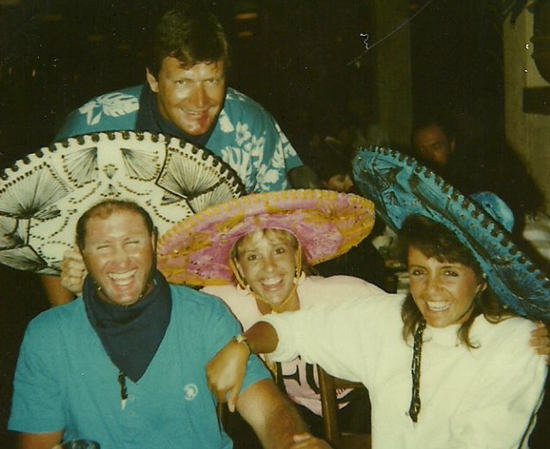

1989 Dave Parrington, Gary Watson, Antoinette Wilken and Jane Figueiredo in Houston.

Dave Parrington, Jane Figueiredo, Rhodesian diving coach Ron Ward

- Hits: 5334