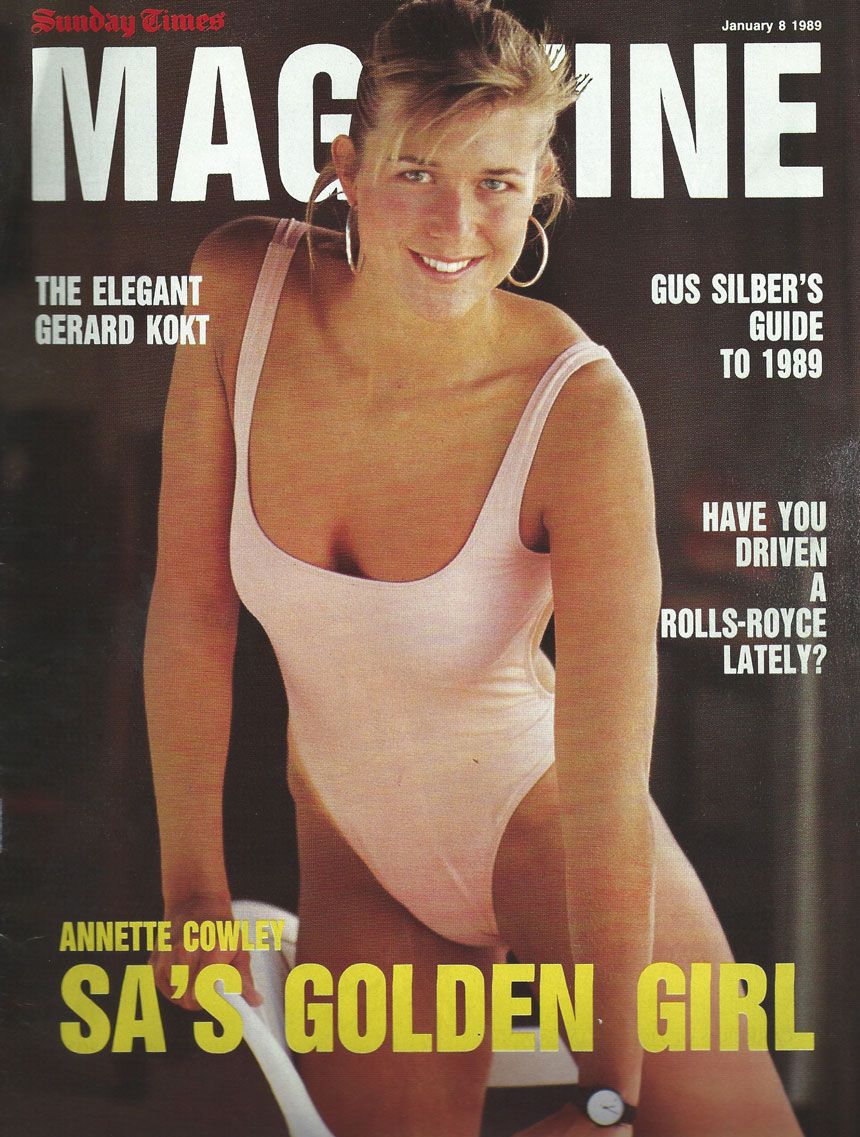

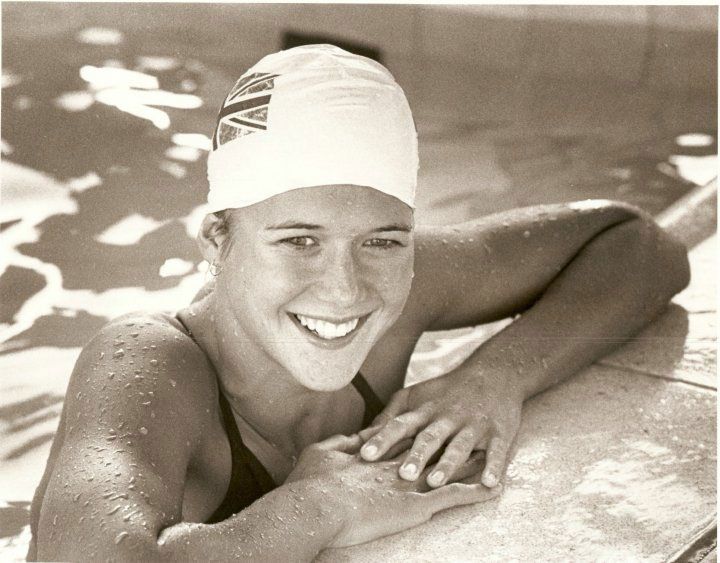

Annette Cowley

Annette Cowley was a Western Province swimmer from Bellville, where she attended Settlers High. Annette started swimming at age 9 when she was spotted by local coach Tom Fraenkel. Although he was based some distance away in Constantia, Annette had the support of her parents who transported her to training every day.

In 1981 at age 15, she finished second in the 200 freestyle at the South African swimming championships in Port Elizabeth, and in 1982 won the event, and set a new SA record in the heats.

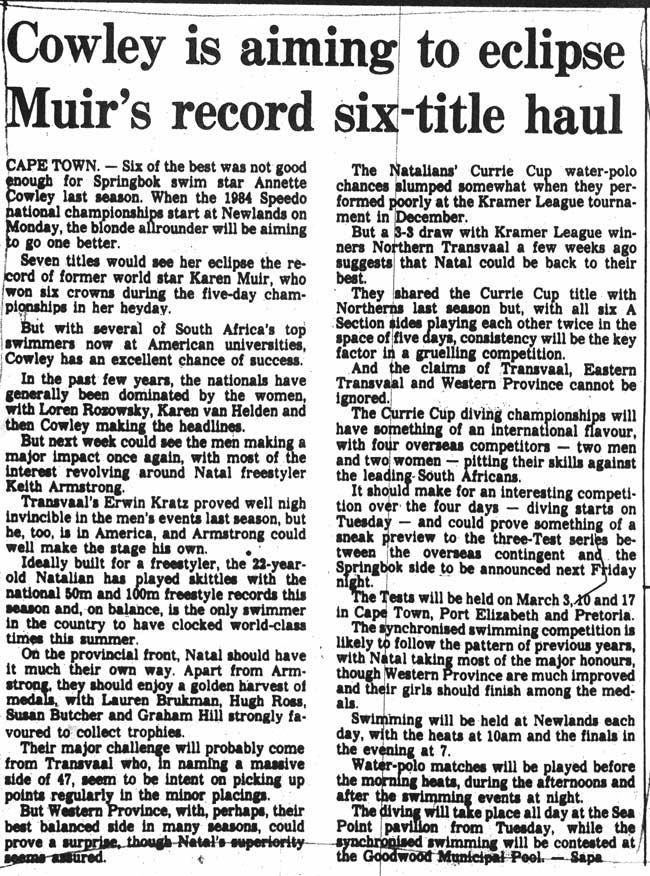

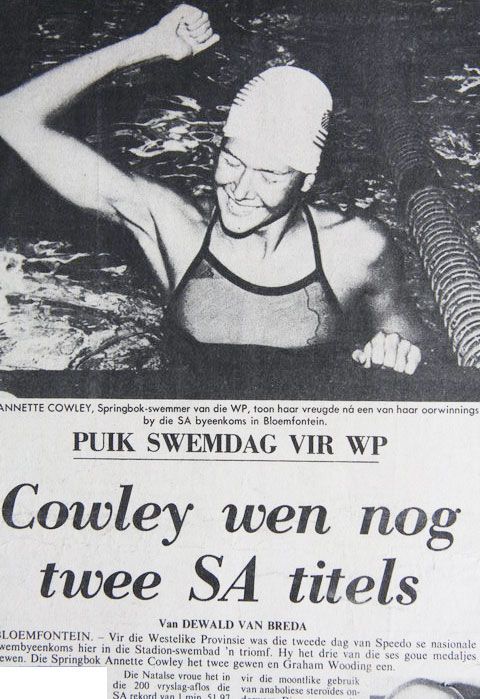

In 1983 she won 6 events at nationals, helped perhaps by the retirement of backstroke and freestyle champion Karen van Helden. Erwin Kratz also won six events at the nationals in 1983, following Karen Muir, who achieved the same in 1969, and Paul Blackbeard in 1975.

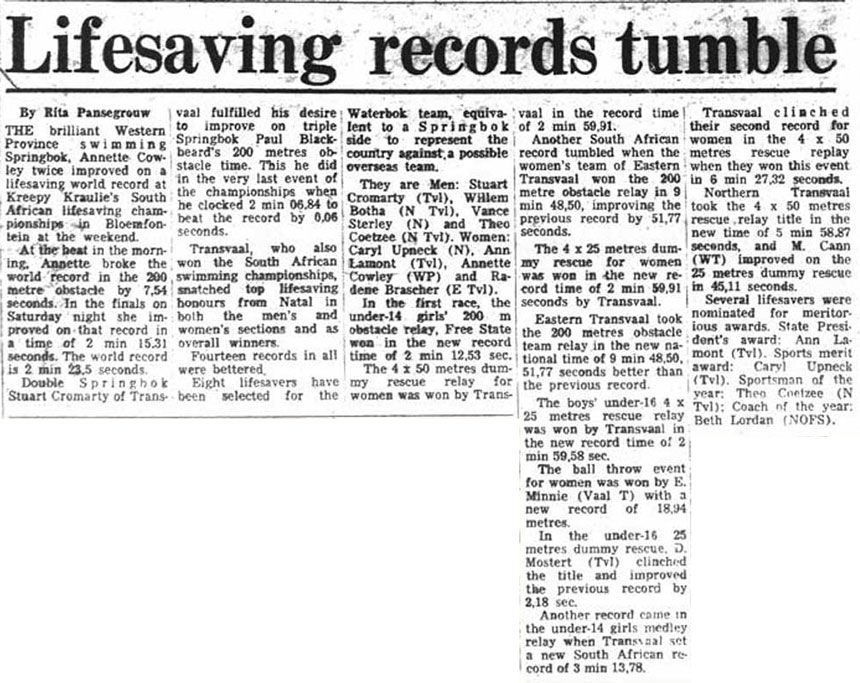

After swimming nationals, she found time to compete in the South African still water life-saving championships, where she was awarded Springbok colours after setting a new world record in the 200m obstacle race.

In 1984 she again won 6 events, and by 1985 she won a scholarship to swim at the University of Texas, under US Olympic coach Richard Quick.

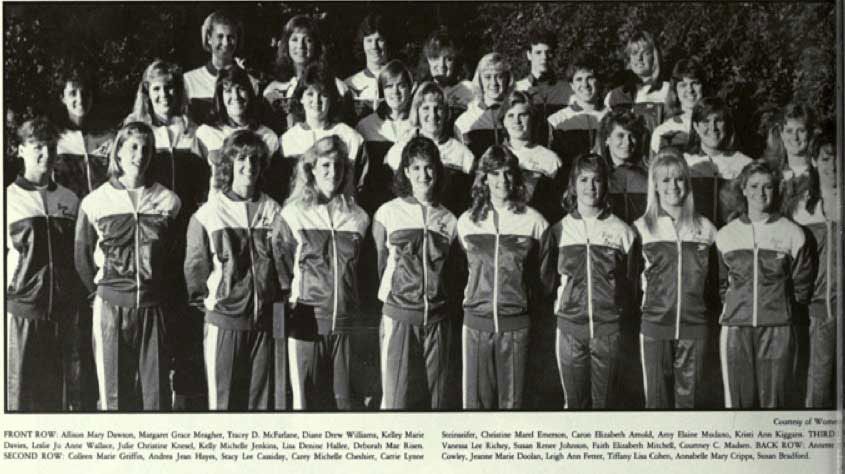

Competing at the Texan International Invitational on 14th January 1985, Annette finished second in the 200 freestyle. By the 1st March, she became the first Texas swimmer that year to qualify for the NCAA Championships - in the 500 yards freestyle. Annette was a key member of the University of Texas team that won the NCAA Championships from 1985 - 1988.

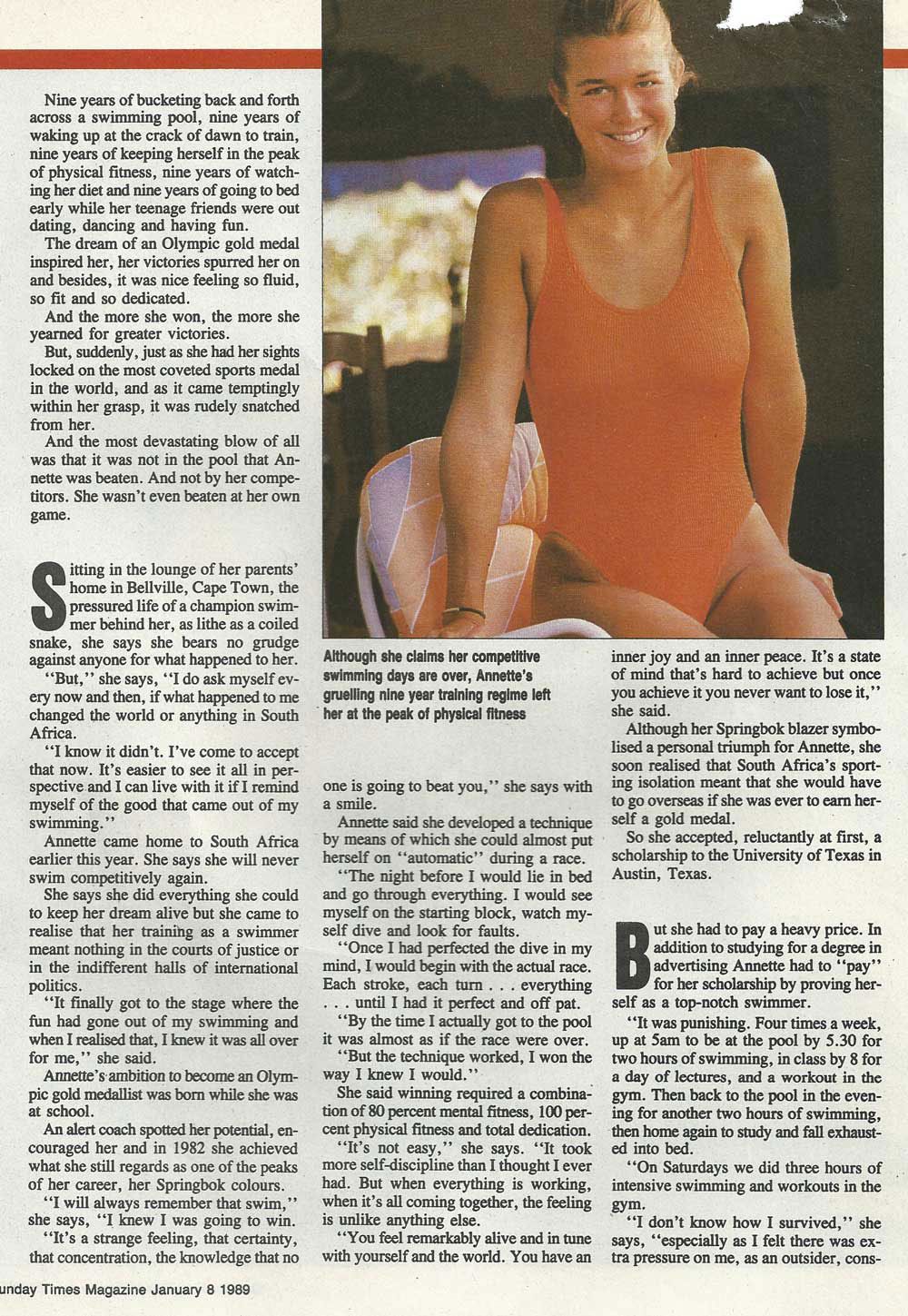

In 1985 Annette applied for British citizenship, through her mother's ancestry, and in May 1986, after assurances from the British Amateur Swimming Association, she swam at the British nationals, winning the 100 and 200 freestyle events. She was eligible for selection to the British to compete at the 1986 Commonwealth Games to be held in Glasgow in July.

Annette was selected, but then the anti-South African lobby threatened to boycott the Games if she and runner Zola Budd was allowed to compete in the Games. The matter went all the way to the British High Court, which ruled against the two South African athletes. Annette, already installed in the athlete's village, was forced to leave and later to sit and watch the swimming from the stands.

At the 1987 NCAA Championships Anntee was a member of the Texas 800 yard freestyle relay that won gold. In 1988 the Texas women's team made history when they won the NCAA title four years in a row - and Annette became an 9 times All-American in helping them achieve that. Annette stayed on at Texas, competing in the NCAA championships and finishing her BSc. degree, before returning home to Cape Town in 1988.

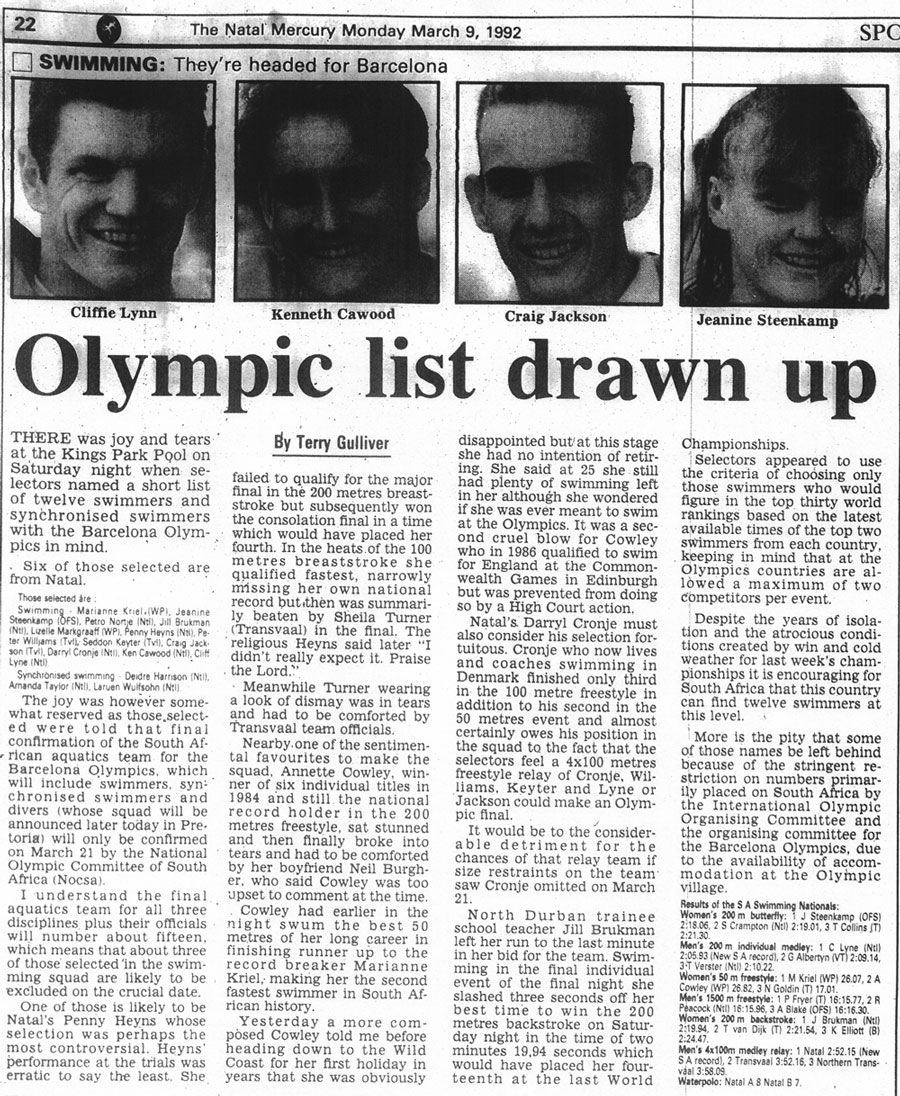

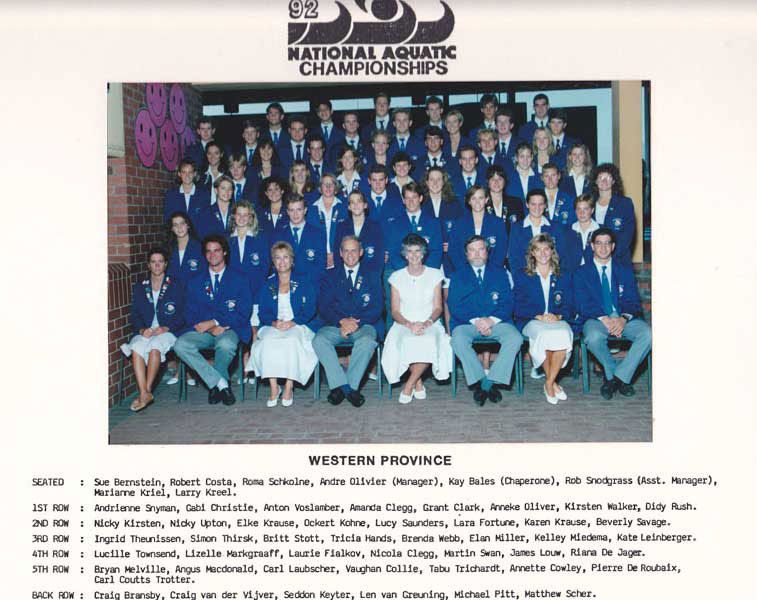

When South Africa was re-admitted to world swimming in 1991 Annette decided to have one more go at making it to the Olympics. The first post-boycott nationals were used as the 1992 Olympic trials in Durban. Annette won second place in the 50 and 100 - both times to WP teammate Marianne Kriel - who was later to win a silver medal at the 1996 Olympic Games.

Kriel's time for the 100 broke Annette's SA record, set in 1984. Unfortunately for Annette - and the new post-SAASU selectors - two-second places at nationals was not enough to be selected for the first South African team to compete in the Olympic Games since 1960.

Annette re-appeared in the swimming press briefly when the Commonwealth Games were once again hosted by Edinburgh, in 2014. She was featured in a BBC documentary titled Boycotts and Broken Dreams.

Today Annette runs a business in Cape Town. Her involvement in swimming centres on her twin daughters Georgina and Olivia, who attended Herschel Girls High School and swam at Swimlab Aquatic Academy (2011-21). Olivia won the 50m butterfly at the SA championships in 2018 - at age 15. In 2022 both girls won scholarships to swim at the University of North Carolina. Olivia set a new SA record for the 50m backstroke at the 2023 South African Championships.

‘I put on a brave face but I did cry’

July 13, 2014

The South African-born Annette Cowley has finally swum in the Edinburgh Commonwealth Games pool after her boycott pain of 1986

“THEY say water is a great healer,” notes Annette Cowley, having finally swum in the pool she hoped to compete in at the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh.

Today is the 28th anniversary, right down to the day of the week, that she was escorted from the athletes’ village by police officers after the Commonwealth Games Federation ruled the South African-born swimmer would not be allowed to compete for England.

She was a 19-year-old girl who became a political pawn, caught up in a boycott by 32 countries that saw the lowest turnout since the post-war Games of 1950 in response to the Thatcher government’s attitude towards apartheid.

Now a mum of three, Cowley returned to the pool with a BBC crew recently for a documentary that will be screened this week. It brought back all the old emotions — measures of bitterness, frustration, injustice — but also some belated catharsis for being unable to compete in her prime due to the country of her birth being a sporting pariah.

“It was kind of a strange day for me because we went to the pool and I felt very emotional when I walked in. My heart was racing, but it was wonderful because they actually cleared the pool for me and I had it all to myself. I swam and felt so calm.”

Cowley’s is a complicated story but one worth listening to. She followed in the footsteps of Zola Budd, also banned from Edinburgh in 1986, as a South African of English heritage who attempted to use it to circumvent the sporting boycott, but there is one key difference.

While Budd competed in the 3,000m for Britain at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, when she collided with Mary Decker, the home darling, and for South Africa at Barcelona in 1992, Cowley twice paid the price for her desire to compete on the world stage. She was not only excluded in Edinburgh but also from the South Africa team for the 1992 Olympics despite training hard to put herself in contention.

“I had quit swimming and was working full-time but when I heard South Africa had got back in I went to my boss and said, ‘listen, I have to give this a last shot, I really have to try and make this happen. If I can’t swim for England or Britain, I am going to try and swim for South Africa again’.

I went back and went to trials, probably did the best times I have ever done.” Despite them, Cowley feels the selectors were influenced not to pick her. She was to be punished again for what her critics claimed was adopting a flag of convenience.

“Politically, we’ve had the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, but it has never happened for our sports people. I don’t think they realise how tough it is to train every day relentlessly to be at the top of your game and have those opportunities stripped away from you.” In 1986, her times in the English trials would have been good enough to take gold in Edinburgh.

She refuses to torment herself too much with what might have been but went along to watch the 100m freestyle final. “I just watched the 100m and then left afterwards. It was tough to deal with and I think enough was enough and I just needed to get out of there and have a change of scene. I had been through a lot. I did cry. I put on a brave face for the media, but sometimes I just shut the door or you take it out in the pool. It is easier to cry in the water.”

Her parents, Ron and Sue, then flew over from South Africa to support her at the centre of a media and political storm. Ron, a Cape Town doctor, who died 11 years ago, knew how many hours the youngest of his three daughters had poured into her dream. “He was so involved in my swimming and so passionate about it.

I trained on my own in the morning and my dad used to sit on the side and read the newspaper. It was freezing cold because it wasn’t heated. I would go in and turn blue and he’d say, ‘you can come home, you know’ and I’d say ‘no’. He was lovely to me.”

Sue has also passed away but kept meticulous scrapbooks of Cowley’s career and the traumatic summer of 1986. For years she couldn’t face the cuttings and the memories they invoked. “I put them in a cupboard and shut it.” Yet now she is planning a book and is glad they are there to help her with it.

She has one of the scrapbooks with her as we speak in a cafe in Edinburgh and it reminds you that this was front-page news back then, plus fodder for cartoonists and satirists inside as they showed Thatcher at odds with the Commonwealth leaders with Budd and Cowley in limbo between them. She became an unwitting and unwilling symbol of white South Africa.

“It was very hard to comprehend because nobody ever asked my personal views and opinions. I grew up in a very liberal English-speaking home and this just happened to me and I felt like an innocent victim. I just stood for a symbol of the white South African government at the time and it was also very confusing because I was being asked to do things like renounce my South African citizenship, but I was scared to do that because my family was back home and I didn’t want to be stopped from going back to see them.

It was extremely controversial and very difficult, initially, not having someone with me to help me through the process at such a young age. As a young girl, I was simply trying to get the exposure, get the competition, and maybe have the opportunity to win gold.”

Instead, her childhood dreams died on that Sunday morning in July 1986 when she was marched out of the Games village. “I don’t think anybody who has the opportunities that they have now would understand what we went through. I wasn’t exposed on an international level to anybody, to any of my heroes that I had read about in Swimming World magazine.

You did feel very isolated.” She wasn’t aware of apartheid growing up, living in a bubble well away from its many atrocities. “Where we went to school it was all white kids and now it is very different. My kids don’t know the difference between black, brown, or white, they really don’t, they are so integrated now, which is wonderful, and I feel quite sad that when I grew up in South Africa we never had that.” Her own children are strong swimmers.

“My son, who is 16, seems to prefer water polo and is doing really well. He seems more interested in swimming lately, but I am figuring that might be because there are some pretty girls at the pool. One of my twin daughters is doing really well and winning nationals in her age group. My other daughter is more into ball sports. They have to figure it out for themselves.”

She missed them during her trip to Edinburgh but it also gave her time to explore the city. “I never got to see how beautiful Edinburgh was — the history, the buildings — so this time round I have really taken full advantage. I have walked and walked and walked. There’s a lot of hills and steps.”

Yet it was the short flight down into the Commonwealth Pool at Meadowbank that was the most significant for her and, after a 28-year wait, that moment of calm isolation in its healing waters that followed.

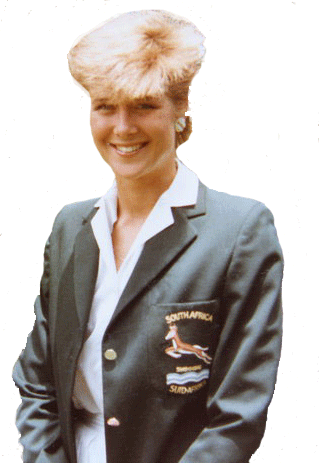

1984 Springbok swimming team.

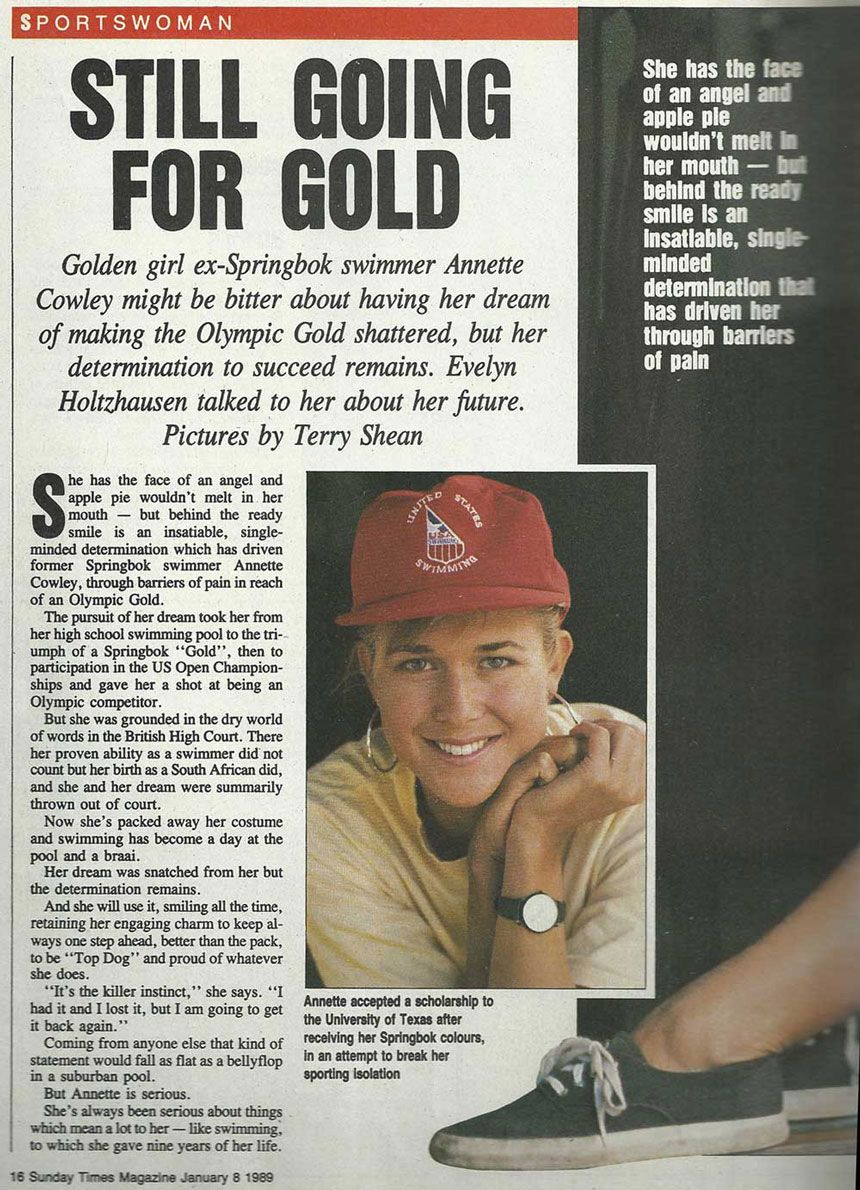

Coach Tom Fraenkel with star swimmer Annette Cowley