Politics

Politics in South African Aquatic Sports

Politics has always played a role in Soutrh African sports - and probably will continue to do so into the 21st century as the ANC government continues to enforce racial quotas on team selection for all teams and at all levels of competition.

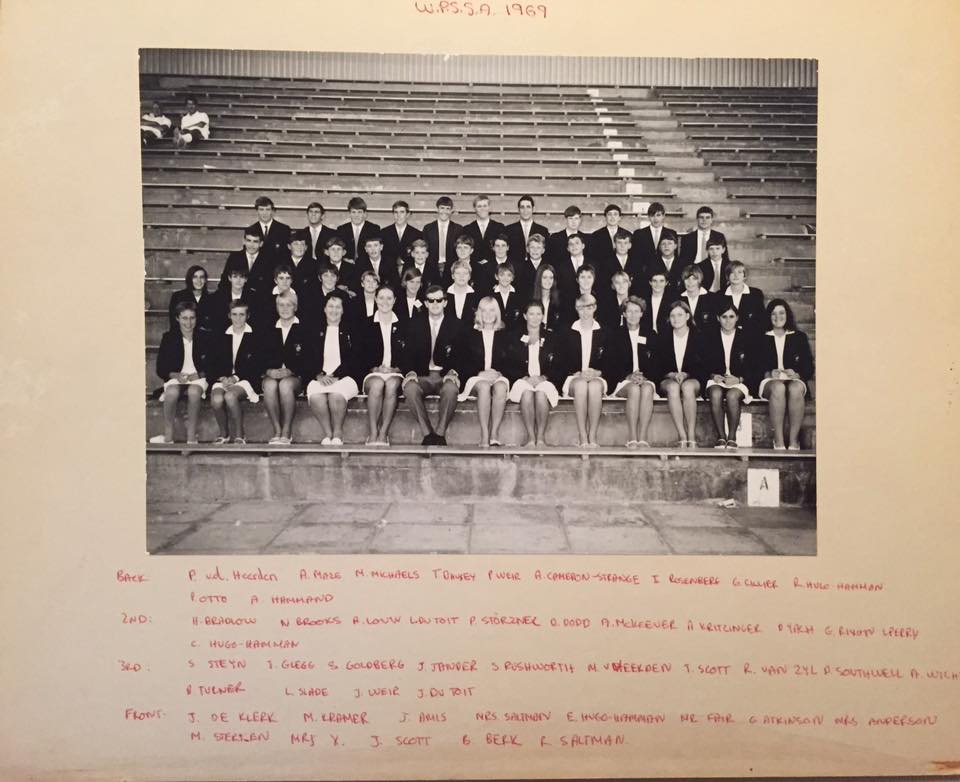

From the early 1960s until 1991, South Africans were barred from officially participating in international events like the Olympic Games and the FINA World Championships. There were some exceptions, like the SAASU President Harry Getz being the Chief Referee at both the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Games swimming events. Unfortunately, world record holders like Karen Muir, Ann Fairlie and Jonty Skinner were never allowed in.

Politics in South African aquatic sports

Politics has always impacted sporting activities, wars, boycotts, conscription, etc. In the campaign to enforce majority rule, sports boycotts were used by politicians as a weapon of war.

"There can be no normal sport in an abnormal society - SACOS"

"Sport and politics should not mix."

In 1900, when the South African Amateur Swimming Union was founded, Natal and the Cape Colony and the rest of the British Empire, was embroiled in a war of occupation with the two republics in South Africa. Many members of the local water polo and swimming clubs were soldiers who fought and died during that war. Men like Ted Wearin from Australia came to fight in the war, and many stayed to enjoy the spoils of victory and expand aquatic sports in the unified colonies and republics of South Africa.

The politics of culture has also played a major role in the history and development of aquatic sports at South African schools. After the war the British tried to 'Angilicise' the Afrikaner children through the schools, but the Afrikaners resisted and set up their own schools. Although different languages were used, the Afrikaans schools soon copied the style of the English schools, which were modeled on their Grammar Schools, which design was copied by some Afrikaans schools. Sports was an important part of the culture in these schools, although the Afrikaans schools were to become dominant in rugby while the English schools focused more on cricket (generally speaking) and aquatic sports were arguably less popular at Afrikaans schools than the English. On manifestation of this preference is the existence of swimming pools at more English schools, although the fact that Afrikaans was almost exclusively the language of the platteland schools also had an impact on this phenomenon.

Although race now dominates the discourse in sport and politics in South Africa, it only became a major issue in sports after 1960. In the struggle for political power in the country, the international sports boycott was used as a weapon against the whites in South Africa. Children, like Karen Muir, were targeted and denied the opportunity to compete at the Olympic Games.

In the post-1994 South Africa education and sports have become completely dominated by the politics of race. The ANC government continues to use the race as a weapon, as it struggle for dominance continues. Interestingly the world that supported their struggle against racism is fully in support of it's own brand of extreme racism it now tries to enforce on South Africans.

Racial quotas in South African aquatics sports

In 2019 the South African government, through the national governing body, still tries to enforce racial quotas on team selection in aquatic sports.

This policy particularly affects team sports - like water polo. It is applied from the school level to the various national teams. Teams are disqualified from competitions if they don't field the required number of black competitors.

The International Aquatic Sports Boycott : 1961 - 1991

The reasons and justifications for the exclusion of South African competitors from international competition for 30 years has been document elsewhere, although there is little if any research on the effect it had on the competitors.

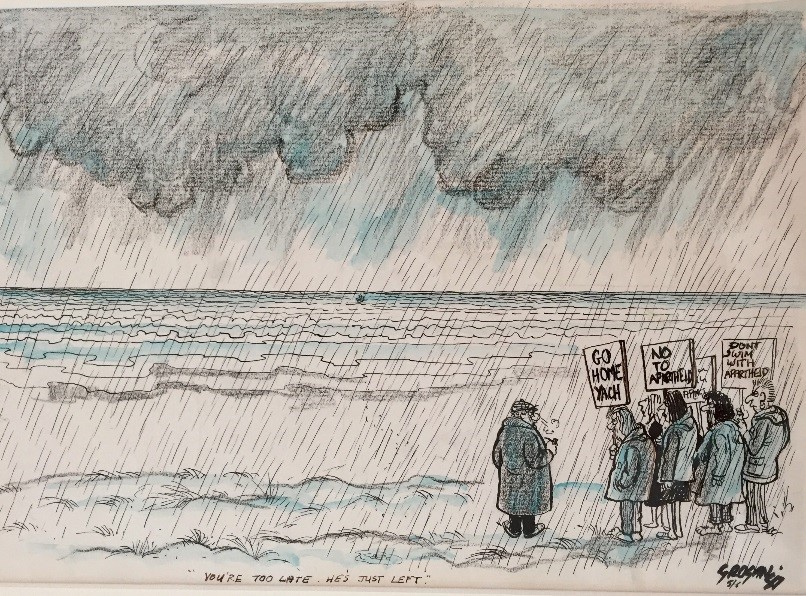

The campaign for global vilification and boycotting of South African sportsmen was a theatre of operations in the war for political dominance in South Africa - where an early victory was the expulsion of the SA Table Tennis Federation from its world governing body in 1956. For swimmers of the boycott era it is a subject particularly poignant interest - the man awarded the leadership position of the new national governing body in 1991 was non other than Sam Ramsamy - the principal strategist of the struggle against apartheid sports from the mid-1970s.

Much has been written about the international campaign to exclude South African competitors from international competition, and the accepted view is that the boycott helped to bring down the white minority government. Little attention has been paid to the effects of the boycott on sportsmen. There are many reasons for the lack of interest about the effects of the boycott on the sportsmen.

One reason is probably because they were never the intended targets of the campaign - which was always about political control of South Africa. The sports boycott was (and still is) a convenient weapon in the ANC's war - and the sportsmen (of all colours) were acceptable collateral damage. Of course the South African government also used propaganda as a weapon in this war and both sides were guilty of murdering innocent bystanders in the more violent aspects of the war. If teenage swimmers had any views about the international sports boycott at all, most (white Afrikaners like me) accepted it is a necessary sacrifice in the war against Communism and terrorism - just like many American victims of their 1980 Olympic boycott accepted it as a valid action against the Soviet Union. Besides - anyone good enough could get a scholarship in the USA and compete in the NCAA’s, which is the world's toughest swimming environment.

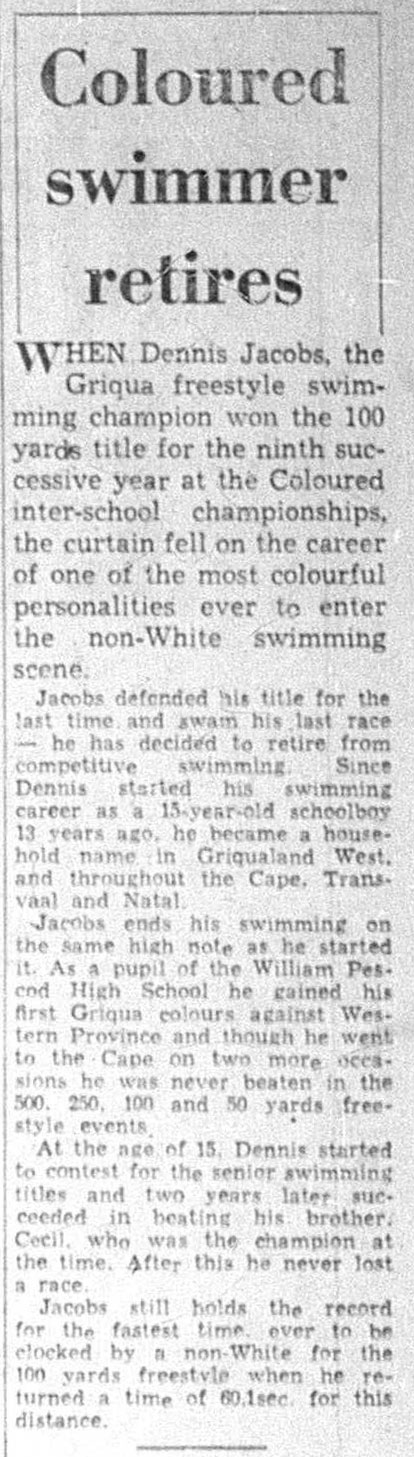

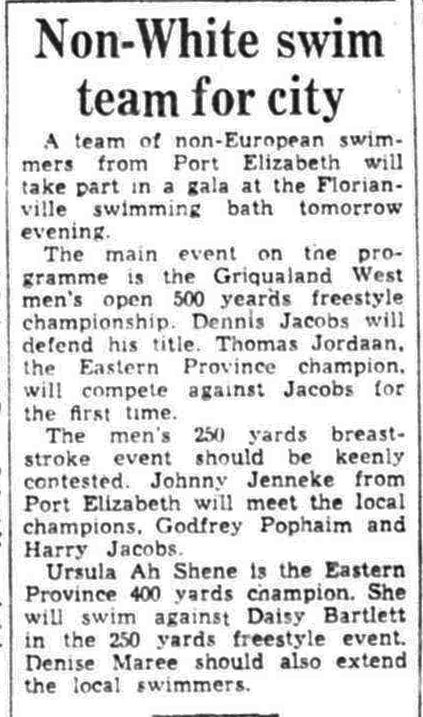

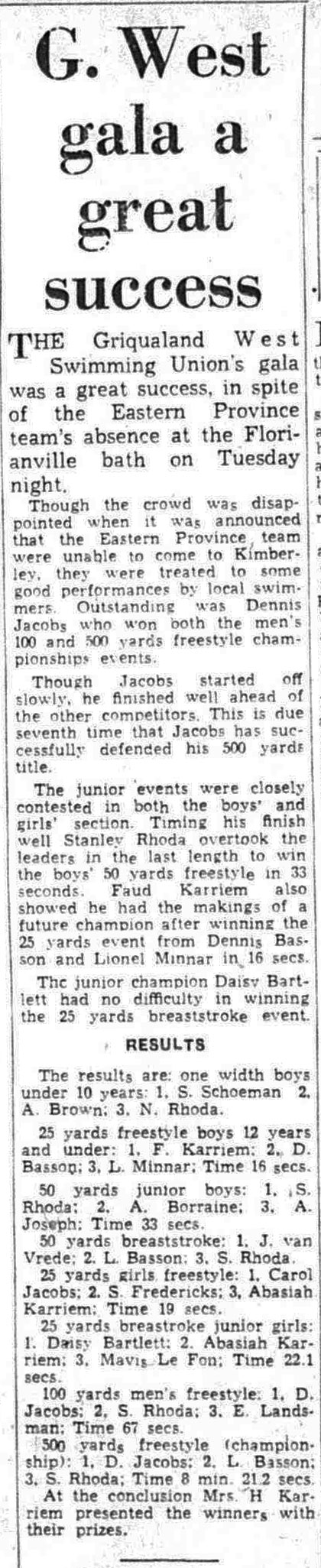

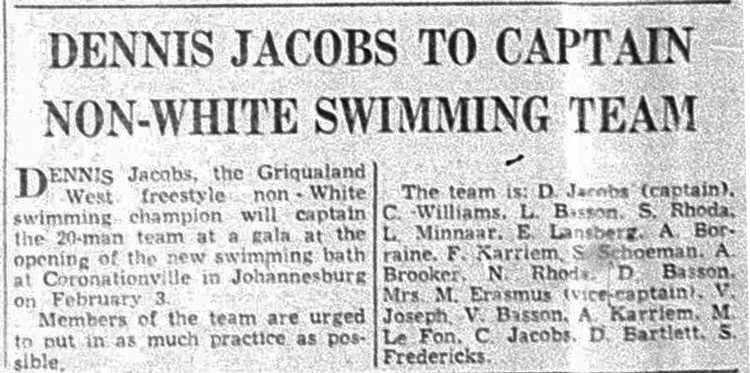

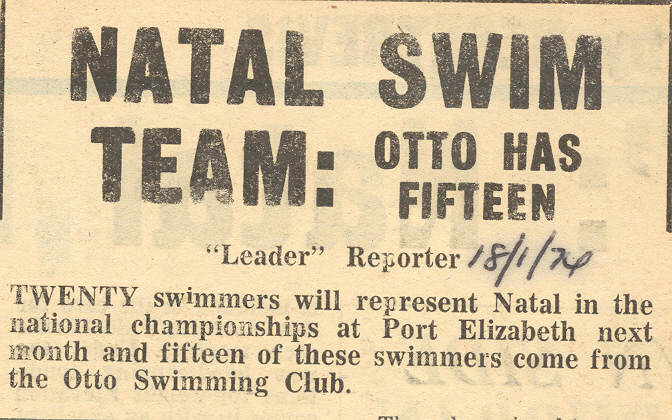

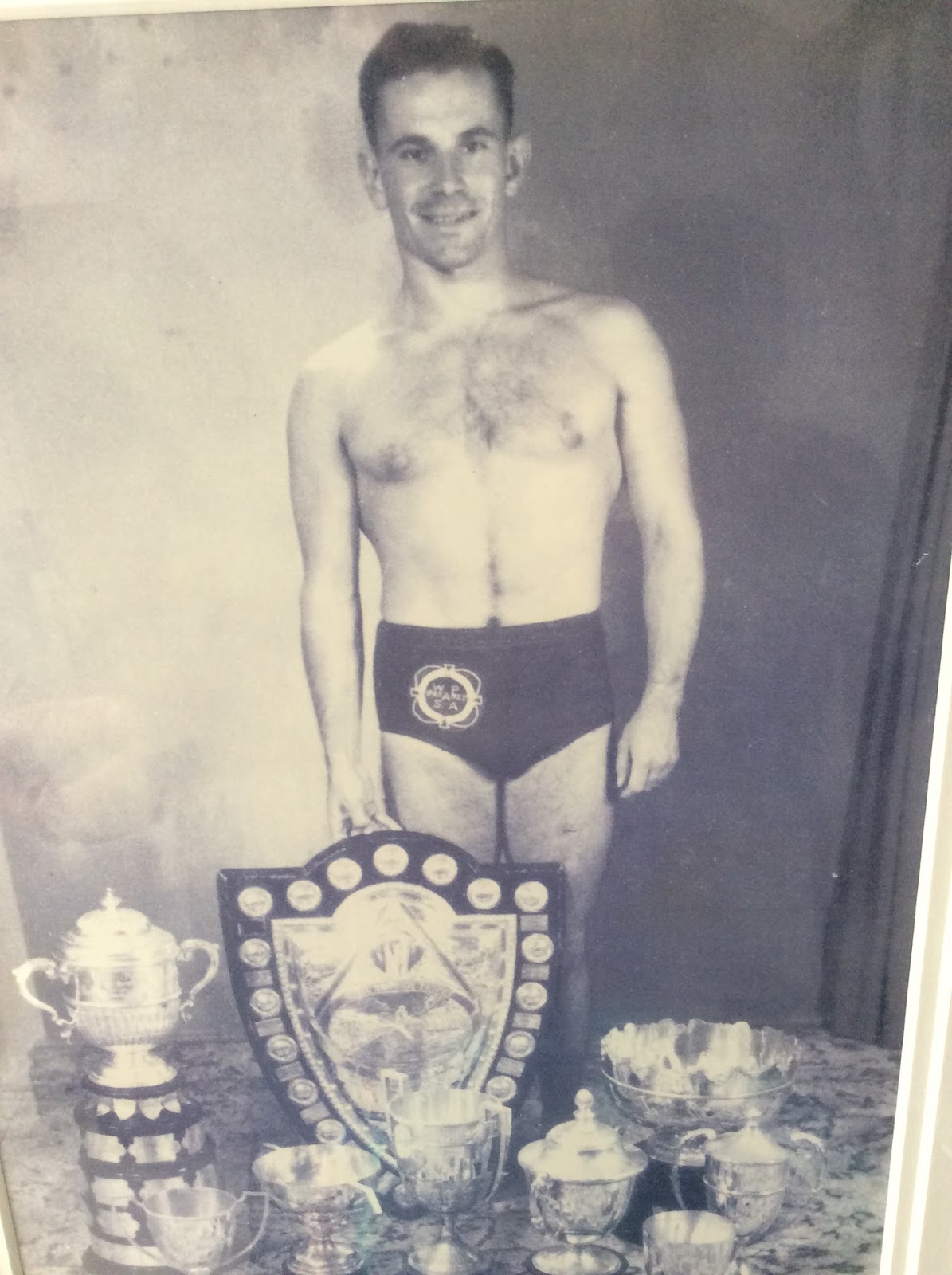

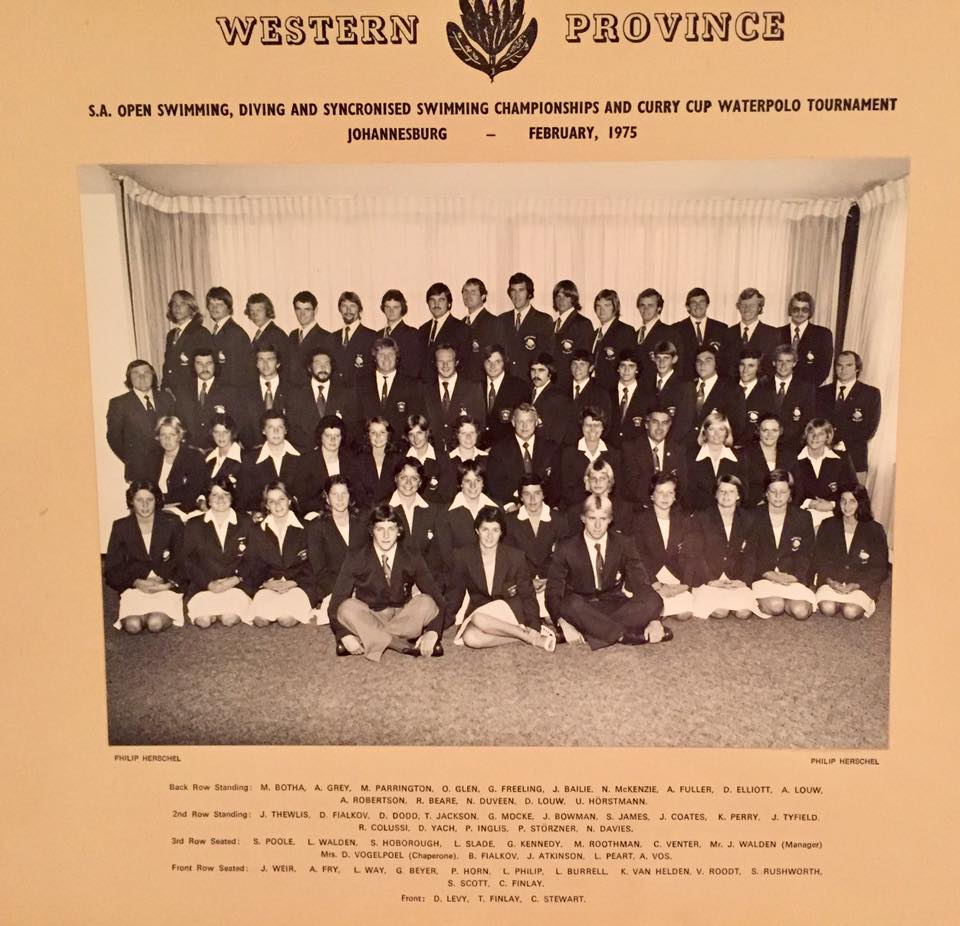

For the (white) kids who lived in South Africa, the boycott was a reality mostly accepted and ignored. Nationals still took place every year - SA records were broken, and Springbok colours remained the most revered status one could aspire to. Even for Karen Muir - holder of a world record at the 1966 nationals - winning a South African title for the first time, in front of her peers, was a special moment. SAASU's attempts integrate black, white and coloured swimmers resulted in the participation of some coloured swimmers at nationals, where they did not do well. For swimmers who had to achieve qualifying times to swim at nationals, it probably rankled that some people got a free entry to compete - and that was probably also the extent of their interest in the exercise. The South African Championships was a big deal for the competitors, all of whom had worked long and hard to get there. Performance - winning - was the only criteria - and the handing of gold medals to swimmers beaten by Rhodesians was also viewed as demeaning by many competitors. It would be 25 years before a non-white swimmer wins a national title - as Raazik Nordien did in the SA Short Course Championships - held in the Long Street baths in 2000.

Sport and Politics is a broad topic which ideally requires its own research project - beyond the scope of this publication. This website aims to provide a historical overview of all the aquatic and related sports in southern Africa - without an undue focus on the political elements. As such the topic is included largely for reference purposes.

However - no history of South Africa can be complete without some reference to the effects of political interference on the actors in that history. The targets of the swimming boycott were largely teenagers - they were soft targets deemed as acceptable collateral damage in the wider conflict over political dominance in southern Africa.

The history of aquatic sports is part of the larger field of sports history, and the international political campaign against South Africans sports is a part of this subject. The emphasis on politics, such racial quotas in team selection, is still very much a feature of all South African sports today - and continues to blight the lives of many people involved in the sports.

The problem is particularly acute in water polo where Swimming South Africa insists on "representative" quota team selection - in 2007 the Western Province water polo team was barred from competing in the final at the interprovincial championships due to the fact that they did not meet quota requirements.

Swimming South Africa policy states: All senior team disciplines (water-polo and synchronised swimming) will be compelled to have a 20% black participation by 2008, and junior teams a 50% black participation, or else such teams will not be ratified.

The wikipedia entry under "Sports and politics" states as follows:

Most famously, the sporting boycott of South Africa during Apartheid was said to have played a crucial role in forcing South Africa to open up their society and to end a global isolation. South Africa was excluded from the 1964 Summer Olympics, and many sports' governing bodies expelled or suspended membership of South African affiliates. It was said that the "international boycott of apartheid sport has been a powerful means for sensitising world opinion against apartheid and in mobilising millions of people for action against that despicable system." This boycott "in some cases helped change official policies."

This is a common justification for the boycott, even if many South Africans would disagree. The 1980 boycott of the Moscow Olympics was similarly justified, although few people would argue it had any effect on the Soviet regime. Marlene Goldsmith states that the South African boycott was due to human rights violations - despite the ANC's calculated use of the boycott as way of achieving political dominance in the country. Some writes (pro-boycott) state that "Under apartheid, especially after the mid-80s, white South Africans felt isolated and knew in their hearts that apartheid was responsible". This patronizing view of (white) South Africans merely reinforces the justification for the boycott, and ignores the realities now evident in South Africa, where crime, corruption and general incompetence has driven many (white) South Africans to emigrate.

These seems to be little interest in recording the views of the victims of the sports boycott in South Africa. As the battle for political dominance in South Africa continues unabated, the sportsmen remain soft targets for ANC politicians, who now justify their actions by claiming there has not been enough "transformation" and try to enforce quotas for team selection.

For some South African athletes, like professional golfer Gary Player and Formula One world champion Jody Schecter, the boycott probably had little impact - and even the rugby players continued to enjoy international competition almost throughout the boycott years.

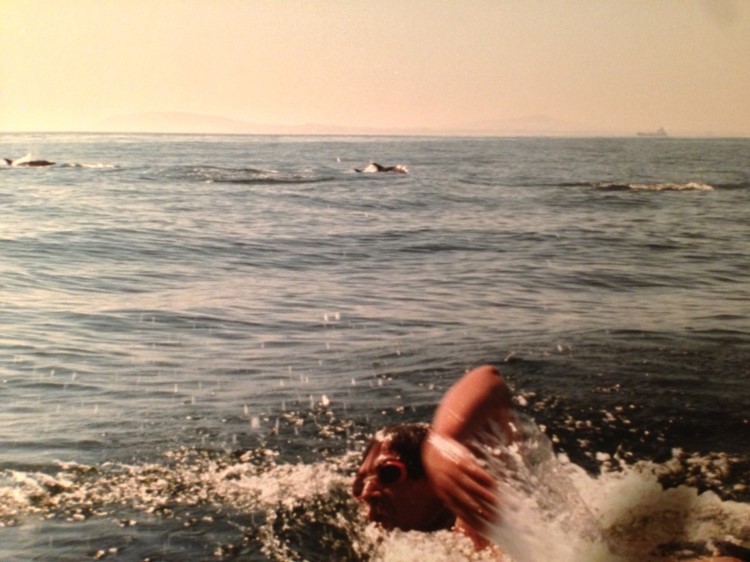

But for the hottest prospects of Olympic gold - swimmers like teenagers Karen Muir and Ann Fairlie, Jonty Skinner and Peter Williams - the boycott meant everything, as they were denied every chance to compere internationally. Although the carrot of Olympic participation was cruelly dangled in 1968 - a Springbok team was selected for Mexico City - but the IOC bowed to international pressure at the last moment and withdrew the invitation previously extended to the South Africans.

This website is dedicated in part to the history of South Africans competitors who were excluded from international competition. Many of the the swimmers the solution was to win a scholarships at an American university - click here to see the list of Exiles.

It is perhaps no accident that the majority of these "local heroes come from the boycott era. In the past South African champions had been allowed to travel overseas as Springboks and compete in the Olympic and Commonwealth Games, while the post-isolation are has seen the swimmers like Penny Heyns and Chad le Clos , who demonstrate the true talent of South African swimming.

Many of these swimmers never returned, and often left a void at the South African championships when they failed to defend their titles. Some returned - like Gerhard van der Walt and Craig Jackson - to win multiple titles at the South African nationals. Other, like Jonty Skinner, Annette Cowley and Gary Brinkman tried to compete for other countries by becoming citizens - but to no avail. Some did succeed - like Rhodesian David Lowe and Simon Gray, who swam for Britain at the Moscow Olympic Games - where Lowe won a bronze medal.

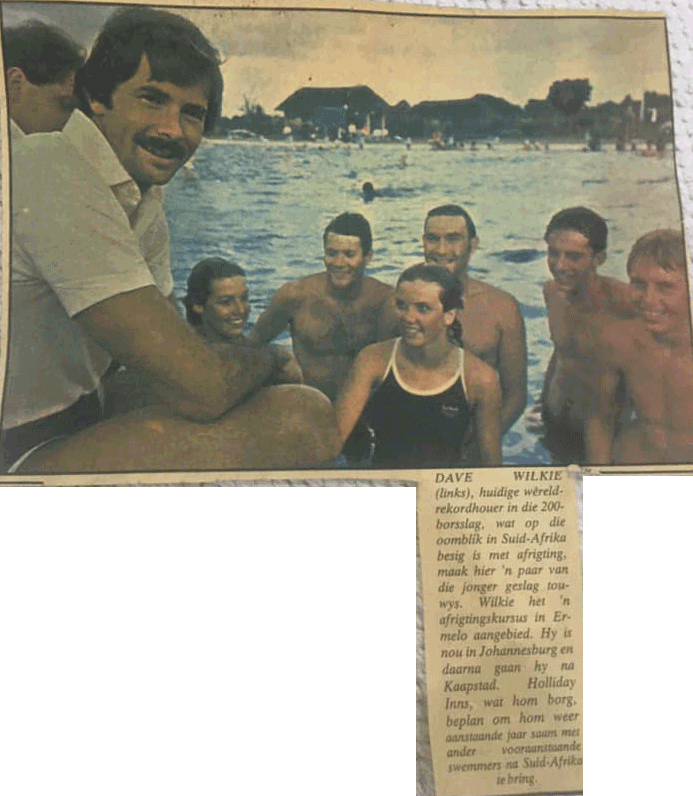

For most of the South African swimmers the boycott had little meaning - Olympic qualifiers are always few in number. Throughout the first decade of the boycott Karen Muir kept South African swimming in international swimming. Olympic medallists Kathy Ferguson and Elaine Tanner had to come to Durban - to test themselves against the world record holder in their event - only to be beaten. In the 1960's other countries also sent their swimmers and water polo teams - Japan, the Netherlands, and Germany amongst them. Some - like Dutch world record holder even came to stay (for a while), while there were visits from famous coaches like Doc Councilman and Derek Snelling of Canada.

The boycott history is well documented - how the ANC inspired the IOC and every international governing body - including FINA - voted to exclude South African competitors, while still allowing men like SAASU president Harry Getz to be the Chief Judge at both the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Games.The propaganda value of sport is analysed in Olympic Sports and Propaganda Games: Moscow 1980 by Baruch Hazan, and also the 1971 ANC publicationInternational Boycott of Apartheid Sport.

While the history of South Africa is currently being re-written or simply ignored - as can be seen from the Swimming South Africa website no mention has ever been made of the these unfortunate kids who missed out.

The 1980 boycott of the Moscow Olympics similarly resulted in a large number of Olympic athletes being excluded form the event - albeit for entirely different reasons. The USA, Canada, Germany, Japan - and 62 other countries chose to punish the Soviet Union for invading Afghanistan - by depriving their own athletes the opportunity to compete in thew Moscow Games.

Australian sports historian Douglas Booth summed up the sports boycott:

In the political struggle against apartheid, protesters and opponents of the South African regime adopted a range of strategies and tactics, including a boycott of sport. This article analyses and evaluates the effectiveness and significance of the sports boycott that passed through various stages with respect to objectives and goals. Boycotters initially sought to deracialize South African sport. By the early 1980s, the sports boycott was one of a raft of resistance strategies aimed at forcing the South African regime to abandon apartheid; by the end of that decade, supporters advocated the boycott as a strategy to build non-racial democratic sporting structures that would assist the transition to a post-apartheid society. While proponents insist that the boycott contributed directly to the abandonment of apartheid, this article suggests that the contribution was more indirect, that the de-racialization of sport in the mid-1970s (under the impetus of the boycott) may have had a greater impact on the discarding of racial ideology in South Africa than commentators have thus far admitted.

Wikipedia:

Sporting boycott of South Africa during the Apartheid era

The 1934 British Empire Games, originally awarded in 1930 to Johannesburg, was moved to London after the (pre-apartheid) South Africa government refused to allow nonwhite participants. South Africa continued to participate in every Games until it left the Commonwealth in 1961.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) withdrew its invitation to South Africa to the 1964 Summer Olympics when interior minister Jan de Klerk insisted the team would not be racially integrated. In 1968, the IOC was prepared to readmit South Africa after assurances that its team would be multi-racial; but a threatened boycott by African nations and others forestalled this. The South African Games of 1969 and 1973 were intended to allow Olympic-level competition for South Africans against foreign athletes. South Africa was formally expelled from the IOC in 1970.

In 1976, African nations demanded that New Zealand be suspended by the IOC for continued contacts with South Africa, including a tour by the New Zealand national rugby union team. When the IOC refused, the African teams withdrew from the games. This contributed to the Gleneagles Agreement being adopted by the Commonwealth in 1977.

The IOC adopted a declaration against "apartheid in sport" on 21 June 1988, for the total isolation of apartheid sport.

In 1980, the United Nations began compiling a "Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa". This was a list of sportspeople and official who had participated in events within South Africa. It was compiled mainly from reports in South African newspapers. Being listed did not itself result in any punishment, but was regarded as a moral pressure on athletes. Some sports bodies would discipline athletes based on the register.Athletes could have their names deleted from the register by giving a written undertaking not to return to apartheid South Africa to compete. The register is regarded as having been an effective instrument.

The UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention against Apartheid in Sports on 10 December 1985.

The names of more than 600 American athletes and sports officials are on a list of 2,500 people who participated in sports events in South Africa from September 1980 through December 1987.

The annual United Nations Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, issued yesterday by the United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid, is part of a United Nations campaign to end international sports contacts with South Africa until that country's system of racial separation is abolished.

The political history of aquatic sports in South Africa falls roughly into these areas :

1. The policies of the national governing bodies like the 1899 South African Amateur Swimming Union, which does not mention racial issues at all; the Cape Town based (coloured?) 1966 SA Swimming Federation (SAASwiF) and its successor SAASA (1975), which then became the Amateur Swimming Association of South Africa (ASAASA).

2. The Sports Boycott 1961 - 1991 which prevented South African teams from competing in international competitions like the Olympic Games and FINA World Championships, although it did not prevent South Africans from swimming in the United States.

3. The Post -1992 era, where politics continues to play a part, through quotas and "transformation".

When a group white English men set up the South African Amateur Swimming Union in 1899, they did it to regulate their own, private, activities - which were mainly playing water polo, with a bit of swimming - there was only one swimming Championship race at the first South African Championships held at Port Elizabeth in 1900. Their constitution was written in English, which was their common language, and it makes no mention of Afrikaans, women or blacks. Over time they would allow women, but they never had an Afrikaner as President, nor did they ever have any black members (it was against the law). The Union was founded in the midst of a war - the Cape Colony and it motherland great Britain, had declared war and invaded the neighbouring republics of de Oranje Vrijstaat ( Orange Free State) and the ZAR (Transvaal) only a few weeks earlier, and many of their members were going north on active service.

After the war they happily expanded their affiliations to include the new territories - Pretoria, the new Orange River Colony (ORC), Natal and then also Rhodesia, which drew in competitors from as far north as Ndola and Kitwe. No official links seem to have existed with the Portuguese in neighbouring Mozambique, although South West Africa joined as province after World War I when it became a South African mandated territory .

The politics of race and gender played little part in this process of development. From 1912 when George Godfrey went to the Stockholm Olympic Games as the first Springbok swimmer, the best swimmers were selected to compete in Springbok colours. They competed at the Empire Games and Olympic Games, where they met with some success, and for the 1952 Games a Springbok water polo team was selected, for the first time.

But the realpolitik of the South African political struggle meant that the ANC, PAC and the South African Communist Party were mobilizing world opinion as a weapon in their battle for supremacy in South African. The sportsmen were deemed acceptable collateral damage in this struggle - if not actual cannon fodder. So the amateur sports administrators became pawns in a war they had little power to influence, because they were essentially law-abiding citizens, who could or would not break the law by having multi-racial sports events. In the end they followed the example of the national government and in 1992 SAASU President Issy Kramer handing control of their sports to the new government-sponsored national governing bodies.

In the aftermath of the 1994 elections all control of sporting bodies passed directly into the hands of the government - who appointed new leaders for every sporting code. Control of aquatic sports was given as a reward to Sam Ramsamy, an ANC stalwart and architect of the international sporting boycott against the swimming. Today he is not only a vice-president of FINA, but also a member of the International Olympic Committee.

The new national governing body, known as Swimming South Africa (following the British naming convention for sporting bodies) is funded by the government, with objectives aimed at achieving "transformation" in aquatic sports. This means teams must represent the demographic makeup of South African society, in practice - teams, and administrations, must be largely black. The Swimming South Africa Constitution states : ‘Transformation’ shall mean the strategic process throughout SSA structures to re-dress the previous inequalities and to cater for the needs of the majority of the populace.

The effect of these policies has been the introduction of quotas, which has a significant effect on water polo in particular, where teams are required to have a minimum number of black players to be eligible to compete in championships. As a result players have left South Africa to compete for other countries - see the article on former national team captain Sarah Harris - now playing for Australia.

Listed below are a few articles related to aquatic sports history - both from South African and elsewhere, to provide a perspective, and also so articles related to the sports boycott.

Boycott readings

Sam Ramsamy - To the victor, the spoils - ANC activist to IOC Member and FINA Vice President

Morgan Naidoo - Activist and swimming administrator

Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott - Douglas Booth

Apartheid on the run - The South AFrican Sports Boycott - Rob Nixon

SACOS - The role in South African sport - MA Thesis by Noel Goodall 2004

The ties that bind - South African sports diplomacy 1958 - 1963

Sports and the liberation struggle : a tribute to Sam Ramsamy and others who fought apartheid sport - by E.S. Reddy (Former Director, United Nations Centre against Apartheid)

Sports boycott as a political tool - by Marlene Goldsmith

Sports Diplomacy and Apartheid South Africa by Alex Laverty

Creepy crawlies, portapools and the dam(n)s of swimming transformation by Ashwin Desai and Ahmed Veriava

Swirling Shades Of Gray - Sports Illustrated article - May 16, 1983

The Effect of Sport Boycott and Social Change in South Africa: A Historical Perspective, 1955-2005 by P. Nongogo

International Boycott of Apartheid Sport - Paper prepared for the United Nations Unit on Apartheid in 1971.

Are sports sanctions and boycotts a pointless exercise?

The Guardian - Wednesday 2 July 2008

John Traicos and Goolam Rajah

__________________________

Yes

John Traicos

Former South Africa and Zimbabwe Test cricketer

Suspending Zimbabwe from inter-national cricket will have little or no

political impact because there are greater issues at stake - Robert Mugabe may like cricket but power and position probably matter most. It is unrealistic to expect sanctions to effect political change by putting pressure on those in power if a sporting body is controlled by politicians and has to adhere to the laws of the country, regardless of whether or not it agrees with them. In any case, anyone upset by a sporting boycott can do nothing about it since the right to vote currently has no relevance in Zimbabwe.

In fact, most sports reflect high standards of sportsmanship resulting in good lines of communication that can often be beneficial in overcoming political and religious barriers. In that respect it is very unfair to punish individual Zimbabwe cricketers or Zimbabwe Cricket for government policies especially when you cannot confirm that they voted for the political party you are trying to punish. Sport should be kept separate from politics as far as possible. While sport has a strong national and representative element - it is usually every top sportsman's ambition to represent his country - it is also individual and personal.

It would be very difficult to achieve an effective ban across all sports but it would be wrong to suspend Zimbabwe Cricket when, for example, the country's athletes can compete at the Olympics this summer. History also tells us that boycotts at the Olympics have had minimal impact. It is the innocent, hard-working sportsmen who suffer instead of the politicians.

People highlight the example of South Africa and how apartheid ended due to sanctions. Having experienced the reality when I couldn't play for South Africa in the 1970s I believe that while sporting sanctions were not liked by South Africans in the 70s and 80s (in fact sport survived through rebel tours), there were greater influences in effecting change. These were economic and cultural isolation, the growing power of revolutionary elements in the 80s and the increasing violence in the country. There was also a realisation by leading whites by 1990 that South Africa (like Rhodesia in the 70s) was fighting a war it could not win.

So, how do you solve the problem? The political situation can be changed peacefully through the holding of free and fair elections or aggressively through external economic and military pressure. Neither of these options seems likely in the short term. Instead a negotiated settlement may be possible if the arrangement gives Mugabe, his military leaders and the MDC a role in a peaceful structure that can in due course provide a transition to normality.

____________________________

No

Goolam Rajah

General manager of the South Africa cricket team

Frankly, I think it is crazy for anyone to say there is no place for sporting

boycotts, or that they are ineffectual. South Africa is living, breathing proof that they can have a profound and dramatic effect for the better.

Sportsmen who claim their "innocence" from the real world are deluding themselves. When cricketers came to South Africa on the Mike Gatting-led rebel tour in 1990, they claimed they were just here to play cricket and knew nothing of politics. Sorry - their mere presence meant they were endorsing the apartheid regime and that was the view of 90% of the population.

One has to be able to look at the big picture and there is always a price to pay for attaining what is "right". The vast majority of white cricketers who couldn't play against the best teams in the world during our 21-year period of isolation were innocent but that was a very small price to pay for the emancipation of 40 million people.

The point about sporting boycotts is that they draw the world's attention to what is happening within the borders of despot countries. Eddie Barlow started the sporting campaign against apartheid back in the early 1980s when he led his team off the field in the middle of a Currie Cup game at the Wanderers and told the press: "So much, but no more." The Gatting-led tour, I believe, inadvertently played a very significant role in ending apartheid because the government of the day hated the worldwide attention and embarrassment which it created.

Admittedly, a sporting boycott of Zimbabwe isn't going to mean much to Robert Mugabe personally, but any country which maintains normal sporting ties with Zimbabwe is, in effect, endorsing his regime. Once that message is made clear, prime ministers, presidents and their cabinet ministers will be less inclined to turn a blind eye. Sport is both a window into a country and a spotlight on it. I have seen and felt the effects of a sports boycott working.

I have some wonderful friends in Zimbabwe, in Zimbabwe Cricket for that matter; do you think I want to put them out of work, or deny them the pleasure that cricket brings? Of course I don't. But they would rather have democracy and a functioning economy than play the game while all around them is morally and financial bankrupt. As we used to say in South Africa: "No normal sport in an abnormal society." That can and should be applied to any country.

Rajah spent much of his life living under apartheid. His view is personal and not made on behalf of the national team or Cricket South Africa.

Click here to read comments from readers of this column

In 2008 an article was published in the Sunday Times, which resulted in a Commission of Enquiry into Swimming in South Africa.

Fear Factor Sinks Swimmers

While South Africa struggles to come to terms with its worst Olympic performance in 72 years damning claims have emerged of racism, threats, assault and victimization by top swimming officials before and during the Games.

In the firing line are head coach Dirk Lange and Rushdee Warley, manager of the team in Beijing. Allegations against the pair, which paint a picture of a culture of fear in SA swimming, include:

Swimmer Shaun Harris claimed this week that Lange, a German national, hit him in the face at the world short-course championships in Manchester earlier this year and warned him:“ Now shut up, I’ll knock you the f**k down.”

At a meet in Japan in 2007, Neil Versfeld claims Lange responded to a question from him about Olympic trial dates by saying, “Neil, you’re f****d, you’re not going to Olympics.”

Lange is accused of standing by and smiling while Roland Schoeman and Gerhard Zandberg had a stand-up row at the pre-Olympic camp in South Korea, when Ryk Neethling had to step in.

In his soon-to-be released autobiography, Neethling lashes out at Lange and criticizes his intimidation tactics. He says their relationship was so bad he once refused to have a private meeting with Lange because he believed things would get physical.

Lange’s relationship with SA’s US-based swimmers is known to be at rock-bottom.

Warley has been accused of racism, once when Lange allegedly told Harris the manager didn’t like him because he was “white and Afrikaans”.

In the other instance, Jean-Marie Neethling claims she was warned by Warley not to speak Afrikaans after doing so at this year’s world junior championships in Rio de Janeiro —because it was “the racist language”.

Warley was accused by Harris of twice telling him to “f**k off” when he first asked for a swimsuit at a hotel during the short-course championships. After haggling, Harris was allegedly told: “Take the f*****g thing and f**k off.”

Suzaan van Biljon was reduced to tears after Warley apparently screamed at her over a breach of protocol in Beijing. She has since been called to a disciplinary hearing.

Lize-Marie Retief was scolded for having a “God power” tattoo (actually a cokie-pen drawing).

Two groups of swimmers separately complained to the chef de mission in Beijing about treatment meted out to them by Warley; and Four swimmers, among them Melissa Corfe, had a frantic run around to secure Chinese visas in South Korea because Warley apparently hadn’t cross-checked their accreditation numbers with their passports.

Former Olympic coach Wayne Riddin spoke angrily about the Swimming South Africa (SSA) administration.“

Every kid wants to swim their heart out for SA, but their morale is low because of the administrators. They’re so scared that they duck away from management,” said Riddin, head coach of the Seals club, which had four swimmers in Beijing.

“I’m prepared to put my career on the line by speaking out because SSA has stuffed things up these past four years.“

Dirk and Rushdee have to go. Things can’t go on this way.”

Riddin expects little to be done in the wake of the Games fiasco, citing many examples where problems had been brought to SSA’s attention, only to be ignored.

“Dirk was my coach, we had a good relationship,” said a despondent Harris. “I want peace, but I have to stand up for the swimmers.”

Speaking from the US on Friday, Neethling said: “It’s time something is done. The atmosphere is terrible.”

There’s also unhappiness over Lange’s role in Beijing. Despite being head coach of the SA team, he was accredited by Eurosport, for whom he did commentary. Lange cleared this with SSA on the basis that it would allow one extra coach to travel with the team, but this was extraordinary, given that his chief job was to coach South Africa in Beijing.

When the allegations were put to Lange, he defended each one. He said his Eurosport work never kept him away from his team duties.

“I attended every swim session and was always on pool deck,” he said. “All the swimmers know how it works. ”

He never spent time with the US-based relay swimmers because they had their own coach, Rick DeMont.

Referring to the pool deck argument in South Korea, Lange claims to have stopped it himself— which conflicts with other versions, including Neethling’s.

“I made sure the argument stopped. I spoke to Roland and Gerhard. This thing could happen in any sport. They later shook hands ... I don’t know why it’s become such a big story. (I thought) the argument in Korea was managed pretty well .” Asked about Harris’s assault allegation he said: “I have no idea . I can’t remember. I deny it.”

He said he couldn’t be expected to remember an altercation with Versfeld that occurred 15 months ago, saying they enjoyed a “good relationship”

.Lange claimed the media was picking on him and defended the Beijing Games as a“successful” one for the swimmers. “There were a lot of Africa records. Why are you coming after me?”

He said he never spoke to Neethling because the swimmer flew in separately, from the US.

“He is a guy who must come to me ... I can’t run to everyone. You should ask him (Ryk) about the official warning he got from Sascoc in Korea.

”(This was denied on Friday by Sascoc official Hajeera Kajee, Team SA’s chef de mission in Beijing).

Asked about the poisonous atmosphere within local swimming, Lange said: “It may be the view of some guys, but guys who work with me say we have a good relationship. With people like Ryk, understand I am always attacking him, but it’s based on performance.

”There is speculation that his contract, which runs until the end of 2008, won’t be renewed. But Lange said negotiations were at a sensitive stage.

Warley denied ever swearing and refuted claims of racism made by Jean- Marie Neethling and Harris. “Against Afrikaans? That’s beyond my comprehension. My kids attend a school that is predominantly Afrikaans.”

He said Van Biljon was in breach of Sascoc protocol for wearing the wrong outfit and he pointed this out to her coach, Karoly von Toros. He says he admonished her for “being rude” and denied screaming at her.

Despite Harris claiming Warley had been in their presence when Lange allegedly hit him, Warley said he hadn’t seen the incident or heard any swearing.

Warley conceded that the atmosphere in SA swimming was “an issue” and that some things, including the strained relationship between Neethling and Lange, had led to unhappiness.

“I have a working relationship with Roland Schoeman, Ryk and Lyndon Ferns. I can’t answer the issues surrounding Dirk. I spoke to Ryk in South Korea, but I wasn’t there to witness the pool deck episode.”

As for the technical glitches and the complaints about him in Beijing, Warley said these were promptly dealt with to everyone’s satisfaction. “But I must stress: the wild allegations are unfounded.”

On Friday, Kajee said the gripes about Warley were less complaints than “challenges”. She refused to discuss the matter regarding Van Biljon, saying, “We’ll deal with it, but I won’t discuss it with you.”

Warley said plans were afoot for an Olympic swimming de-briefing at the end of next week.

Astonishingly, there is no intention to include a single swimmer.

South African Amateur Swimming Federation

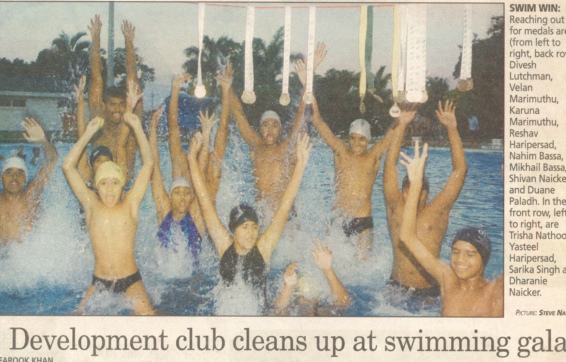

The South African Amateur Swimming Federation has from its birth in April 1966 seen a gradual growth in membership. It now has 4 069 members (1 324 in Natal, 992 in the Western Cape, 873 in the Eastern Cape, 602 in Griqualand West and 278 in the Transvaal). These figures do not include its associate members, the S.A. Senior Schools` Sports Association and the S.A. Primary Schools` Sports Association. Although membership may not be as high as it should be, the growth is encouraging, when one takes into account that the Federation is only seven years old, and that only a few pools are available.

Standard of Swimmers

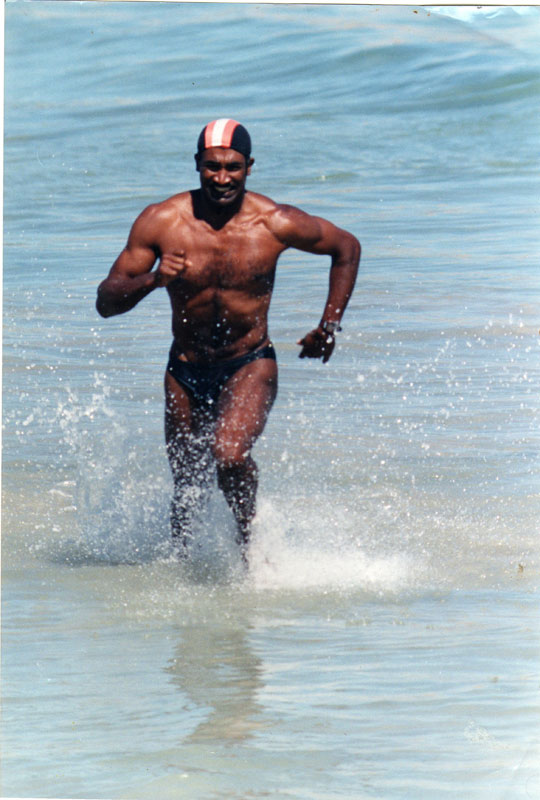

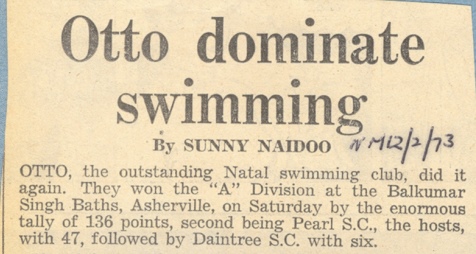

In the short time that swimming pools have been available to blacks in this country, there has been rapid progress. At the beginning of this year, Terry Gulliver, an Australian professional coach engaged by the Federation, said, after a coaching session at the Balkumar Pool, in Asherville, `These six swimmers performed as well as any similar white squad. There is great untapped potential here` (Natal Mercutti 12;`1/73).

Affiliations At the Biennial General Meeting in 1970, a suggestion to apply for direct membership to the world swimming body, FINA, was rejected because there was a white South African body (SAASU) recognised by FINA. Negotiations were initiated with SAASU. The Federation requested SAASU to ensure that future teams should be selected on merit. The first meeting between the Federation and SASU in July 1971 was successful. But the SAASU President later broke his verbal contract by stating `that the teams would be selected on merit but within the framework of government policy`. ` The SAASF then suggested terms for negotiation with the SAASU in September 1971, including the formation of a national controlling body, affiliated to FINA, with equal representation of SAASF and SAASU, and with common trials before national teams were chosen. SAASU rejected these terms and presented counterproposals, including the establishment of a joint liaison committee, which would select national teams `purely on merit`, but which would be chaired by the chairman of SAASU. The SAASF, in its turn, made counter-proposals. The Federation also felt that the chairman should be elected either by popular vote or by an agreed basis of alternation until the need for the two bodies ceased. SAASU replied that they were the controlling body affiliated to the inter- national body for all branches of swimming, and called upon the Federation to affiliate to them.

The SAASF Biennial General Meeting held in January 1973 found that affiliation to SAASU was unacceptable and remained fixed in their policy that they wanted only one controlling body in the country with mixed swimming at all levels. The SAASF received an invitation to send competitors to the South African Games, but turned it down because it is against their principles to participate in any competition which discriminates against anyone on the basis of race, colour or creed. South African Amateur Swimming Association This Association was formed in February 1973 under the presidentship of Mr Reggie Baynes, who is also the President of the S A. Coloured Football Association. SAASA was accepted as a member of SAASU. The SAASF does not recognise this body as it feels that the Association is not representative of all black swimmers. Its activities seem to be centred around one pool in the Transvaal. Facilities Facilities for black swimmers are far from satisfactory.

A survey by the Federation showed, for example, that in Griqualand West, two pools serve a black population of over 80 000 while the 30 000 whites have 4 pools, while in Durban, Natal, 185 000 whites have 9 pools built by the local municipality, while 221 403 Indians have only 2 pools. Throughout the country, there are sixteen Olympic-sized pools for whites and none for blacks. The Federation also wrote to 341 Municipalities requesting details on facilities available. Only 114 replied, and the replies showed a total of 120 pools for whites, 21 for Africans, 18 for Coloureds and three for Indians. Sponsorship The Federation has suffered greatly because of lack of funds.

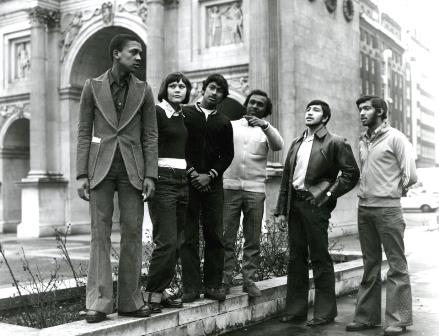

While the white body (SAASU) has received assistance from business houses and from government sponsorship, SAASF has received none. In fact, approaches to the S.A. Sugar Association, the S.A. Milk Board, Coca- Cola Bottling Company, Bata Shoe Company, Oudemeester Cellars, Shell S.A., Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company, B.P. Southern African, Clover Dairies, and the United Tobacco Company, for sponsorship of the 1970 tournament were turned down. Intimidation Over the past few years, officials of the Federation have been intimidated on many occasions. The President, Mr M organ Naidoo, received several visits from the Special Branch. On one occasion the Federation constitution, names and addresses of office-bearers and their occupations were requested. On another occasion Mr Naidoo was threatened with a banning order. In June 1972 he lost his job as a salesman with a liquor firm, Distillers Corporation.

In July 1973 he was refused his passport with no reasons given by the Minister of Interior. Mr Naidoo has subsequently been banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. Application to FINA for Membership After the refusal of SAASU to accept the Federation`s proposal, it found itself communicating directly with the world body (FINA). A FINA com- mission visited South Africa in March 1973. The Commission was met by members of the Federation, who handed over to them copies of the constitutions of their affiliate units, annual reports, gala programmes and other available literature and a copy of a memorandum to be presented to the fourteen-man FINA Bureau at a meeting held in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, during August. In discussions with the Commission, SAASF stated emphatically that if any of its affiliates practised discrimination on the grounds of race or colour, they would be instantly expelled, and repeated that whites were free to join, even if this move might invite prosecution from the government.