Kirsty Coventry

Kirsty Coventry is a Zimbabwean swimming superstar, winning 7 Olympic medals, making her Africa's most successful Olympian. She competed and also trained in South Africa.

Kirsty Leigh Coventry Seward was born on 16 September 1983, in Harare, Zimbabwe, where she attended the Dominican Convent High School until 1999. She learned to swim at home - taught by her dad and mom, and later at the local Highlands SC. After finishing high school she accepted a scholarship to swim for Auburn University in the USA under coach David Marsh and coach Kim Brackin. She spent some time training with South African coach Dean Price in Johannesburg.

On 10 August 2013, Coventry married Tyrone Seward, her manager since 2010. In May 2019, she gave birth to her first child.

Coventry competed at five Olympics, from 2000–2016. With seven Olympic medals, Coventry is the most decorated Olympian from Africa. At the time of her retirement, she had tied with Krisztina Egerszegi for winning the most individual Olympic medals in women's swimming. She won the 200m backstroke at the 2004 and 2008 Olympic Games.

Coventry emerged as the highest individual scorer at the NCAA Championships in 2005, clinching three separate titles in the 200-yard and 400-yard individual medley and the 200-yard backstroke. Her NCAA achievements include seven national titles and 25 All-American honours.

She left the USA to return home to Africa to continue her training, in Johannesburg with Dean Price at the Mandeville Dolfins SC.

"I moved to Joburg to be closer to home. It is difficult to prepare in Zimbabwe as the swimmers are not strong there. So it is nice to train with Dean and experienced swimmers such as Mandy Loots," she said.

Later she went to train in Monaco at the request of the former Charlene Wittstock, a former Olympian from South Africa with whom Coventry had become friends (before Wittstock became the Princess of Monaco). In 2012 she returned to the USA, to train with her former coach Kim Brackin, who is now the head coach for the women at the University of Texas.

Kirsty tried for an eighth Olympic medal when she battled her way into fourth place in the 200m backstroke semi-finals at the 2016 Games in Rio. In the final, she came fourth in 2mins 08:83s in a race won by Hungary’s Katinka Hosszu in a time of 2mins 06.03s.

On 7 September 2019, eight days shy of her 35th birthday, Coventry was appointed "Minister of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation in Zimbabwe's 20-member Cabinet under President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

In 2012, she was elected to the International Olympic Committee Athletes' Commission. She has been serving as an IOC member for eight years. In 2023, she became an elected member of the IOC Executive Committee.

Kirsty is a role model and hugely inspirational figure for many women and young people across Africa and the world of sport. Her memberships on the International Olympic Committee, World Anti-Doping Agency, International Surfing Federation and FINA are playing a key part in expanding the global Olympic movement and the development of sport.

Affectionately known as Zimbabwe's 'National Treasure' and 'Golden Girl', Kirsty continues to invest her time and experience in Africa. She is a member of the ANOCA Athlete's Commission, Vice-President of the Zimbabwe Olympic Committee, provides coaching and swimming lessons at her non-profit organization, the Kirsty Coventry Academy, and has recently launched a program for low-income and underserved areas - HEROES: Empowering children through sport.

Click here to see her swimming website.

September 19, 1983: Born in Harare, Zimbabwe.

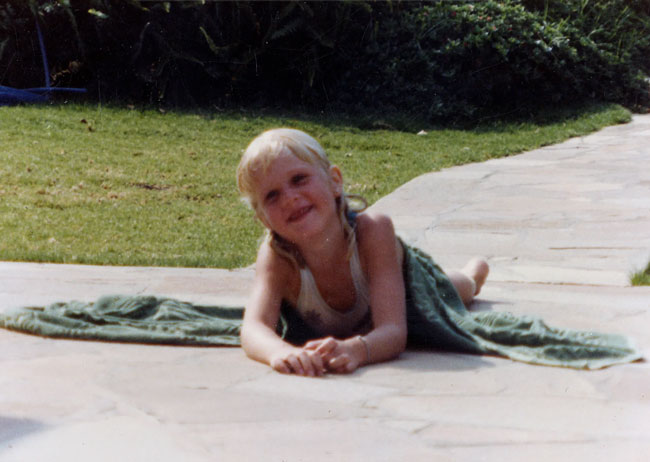

1985: Before she turned 3 years old, Kirsty is already swimming in her backyard pool. Her mother taught her to swim.

1988: Showing signs of competitiveness — her Dad would take her fishing and Kirsty was never content with the last fish she caught, she knew she could catch a bigger one. She often did.

1989: First day of school. 📓✏️

1989: First day at Highlands Club Swimming. This was the first time she learnt about winning, and losing. There were no heated pools, indoor facilities nor year round swimming.

1992: She told her Dad she wanted to go to the Olympics and win gold. 🏅

“Anyone can have a dream, but not everyone has the drive to make it a reality — I did.”

1994: Kirsty volunteers at the swimming events during All Africa Games in her hometown of Harare, Zimbabwe.

1999: Kirsty competes in her first All Africa Games. She won a gold medal in the Women’s Relay team.

1999: She qualified for her first Olympics. Kirsty is only 16 years old.

DID YOU KNOW: Kirsty only started focusing on swimming backstroke when her coach begged her to try it, “just this once.” She’s now gone on to break multiple records and win countless races for the stroke.

2000: Kirsty competed in her first Olympics in Sydney, Australia.

DID YOU KNOW: At just 17 years old, she made it to the semi-finals and came 12th — no Zimbabwean swimmer has ever done this well.

2001: Full scholarship to Auburn University. In the coming years, she’d have an explosive collegiate career. View her collegiate profile. 🇺🇸

2002: First time Auburn Woman’s Swimming wins the NCAA. 🐾

2002: Kirsty competes in the Commonwealth Games and wins gold in the 200m backstroke.

2003: Second time Auburn wins Woman’s Swimming at the NCAA.

2004: Third time Auburn wins Woman’s Swimming at the NCAA.

2004: Kirsty goes to the Olympic Games in Athens. She wins a gold in the 200m backstroke, a silver in the 100m backstroke and a bronze in the 200m IM.

2005: Kirsty breaks her first world record and will go on to break another 6.

2008: Kirsty goes to the Beijing Olympics. It’s here that she wins three silver medals in the 200m individual medley, 400m individual medley, and 100m backstroke. She receives a gold in the 200m backstroke.

It’s during these Olympics that Kirsty breaks the world record for 100m backstroke and the 200m backstroke.

2009: Kirsty re-breaks for world record for the 200m backstroke at the World Championships for swimming in Rome.

“Kristina (previous WR holder) was ahead of her time, an incredible swimmer. I was so proud, honored and in shock to have broken the record.”

2009: Kirsty meets her now-husband, Tyrone Seward. In a kitchen.

2012: Kirsty faces her first injury ever four months before the London Olympics. Then, she falls ill with pneumonia just two months before Olympics. Doctors and surgeons tell Kirsty she will not make it to the London Olympics.

3 weeks before London Games: Kirsty is cleared to compete. 🙌

2012: London Olympics — Kirsty’s amazes her friends, family and competitors by coming sixth place in both her events.

2012: Kirsty get engaged just before the closing ceremony at the Olympics. Tyrone proposes in a kitchen.

2013: Kirsty gets married on the same day she was proposed to, one year later. 💍

2013: Kirsty tours all 10 provinces in Zimbabwe in a quest to learn more about her country and find out where she can make a greater difference.

2013: Kirsty decides to go for her fifth Olympics but knows she needs the best team, the best nutrition, the best coach, the best of everything if she is going to make history again — this time she is aiming to become the most decorated female Olympic swimmer in history.

2014: Kirsty creates the Kirsty Coventry Academy.

2014: She finds her swim team — SwimMac Elite in Charlotte, North Carolina.

2015: Kirsty Coventry Academy is launched.

2015: Kirsty Coventry joins LifeFuels to help with development of the Smart Nutrition Bottle.

“It’s like two birds with one stone. I was looking for nutrition, but also looking for long-term in the sport and health industry.”

2016: Fifth time going to the Olympics in Rio. To be continued…

Win or Lose, Kirsty Coventry is Excited to Represent Zimbabwe at her Fourth Olympics

July 17, 2012: PHOENIX, Arizona

KIRSTY Coventry joins today's edition of The Morning Swim Show on the eve of attending her fourth Olympic Games.

Coventry, the reigning Olympic champion in the 200 backstroke and world record holder, talks about the years since winning Olympic gold and how she has reset her outlook on competition since the 2009 world championships. With the landscape of women's swimming changing greatly since Beijing, Coventry will face tough competition as she sets up to become the third person to win the same individual event at the Olympics three times. Be sure to visit SwimmingWorld.TV for more video interviews.

Jeff Commings: This is The Morning Swim Show for Wednesday, July 18th 2012. I'm your host Jeff Commings. In the FINIS monitor today we'll talk to Kirsty Coventry, who is trying to join that elite group of swimmers who have won the same individual event at the Olympics three times. Kirsty joins us right now from her hotel in Tunis, Tunisia. Kirsty welcome to the show. How are you doing today?

Kirsty Coventry: Hi, I'm good, thank you, thank you for having me.

Jeff Commings: So tell us what you're doing there in Tunisia.

Kirsty Coventry: Well we just figured it would be a great opportunity for me to be based somewhere in Africa for my pre-training camp before we go into London and Tunis just kind of came along as a good idea and in the past I've become friends with Ous Mellouli, and we asked him what the pools and conditions and things were like here and he put us in touch with his federation and things worked out really well and here we are.

Jeff Commings: That's really nice. And speaking of being in Tunisia you've been racking up the frequent flyer miles a lot these past few years. Every time we check in on what Kirsty Coventry is up to you seem to be in a different city not just for competition but for training. Tell us where you've been around the world and why you decided to go there.

Kirsty Coventry: Well we've been all over the place. After World Championships in 2009 I took a year off and moved to Johannesburg, South Africa, and spent some time there with family and friends and then after a year I got back into training and started having a lot more fun again with my swimming and went from training in South Africa to doing a bit of training in Europe and then back to Texas with Kim, my old coach, and then we had four months of good training in Austin and now we're here getting ready for London and things are going good.

Jeff Commings: Now when you took that year off after World Championships was that kind of thinking you were going to leave the sport or were you just taking a break knowing you were still going to go to 2012?

Kirsty Coventry: Honestly I didn't really know. I just wanted some time out, I didn't have the best me. I had the great me if you look at it in regards to my 200 backstroke but I wasn't too happy with my other events in 2008 and everything had become so much about the suits, not so much about the athletes, and there was a lot of controversy. And so I just wanted to take a step back and have time out and be somewhat normal and get to spend time with my friends and family which I did and I loved it and met a great person who's in my life and travels with me and has joined me on this adventure which is super cool. And yes, like I said I took that year off and loved being normal and hanging out with friends and family and then started working out. I kept active, I stayed in the gym and ran a little bit, and then one day got back into the pool and starting messing around with time a little bit and it just kind of progressed from there and I just really missed the sport and wanted to give it one more shot and see what I can do and see how I could push my body.

Jeff Commings: And you're talking about that you have rediscovered your love of the sport, having more fun in it. What was the key to rediscovering that?

Kirsty Coventry: I think definitely taking that year away and just realizing what exactly is important. I think when you're young and you're a young athlete and I've been very fortunate in my career to be successful and very blessed for that but in the moment it's all about trying to win and trying to be the best and I don't think I ever really took everything in so that year was really nice to just take some time out to realize how I had done and I'm very proud of myself for achieving those things but I also was looking for other things in life and I think I found that and I'm just in a good place – I'm in a good space, I'm happy, and I know that I want to try and be as competitive as I can leading up to London and in London as well and I think my year away and taking that time off is going to help me to do that.

Jeff Commings: Now since 2009 World Championships where you set the current world record in the 200 backstroke the landscape of women's swimming has changed pretty considerably. What's your take on that?

Kirsty Coventry: I think it's awesome, I think women's swimming has consistently – every four years, if you look back in 2004 where we went from 2004 to 2008, from where we've gone from 2008 to 2012, it's just really awesome how much better women's swimming is getting and I think that's really exciting. I think that's exciting for the sport, I think it's exciting for us as athletes, and I'm just really — like I said earlier – I'm very excited to be part of that, we're making history and that's fun to do and fun to be a part of.

Jeff Commings: Now I would imagine people like Missy Franklin and others are really pushing you to really work a lot harder.

Kirsty Coventry: Yes, definitely. I think it's – a lot of people ask me which is harder, getting to the top or staying at the top, and it's definitely staying at the top is much harder than getting to the top because you've got certainly more people trying to knock you down. And I'm very realistic about my goals going into London and I just want to be as competitive as I can be and I know that there are a lot of great swimmers out there at the moment and if I can go in and be competitive and have fun and swim some of the fastest times in the world that would be great and we'll just see how it goes.

Jeff Commings: Now as I mentioned at the beginning of the show you're in line to potentially join a very elite group of swimmers who have won three consecutive gold medals in the same event in the Olympics, Kristina Egerszegi did it in the 200 back, Dawn Fraser did it in the 100 free, and you're in line to do that for the 200 back. Has that been a big motivator for you?

Kirsty Coventry: It has. I try not to think about it too much because I think that those types of things, especially that it's such a big deal and it would be such a great honour, but in that, in saying that, it also adds a lot more pressure. And I really want to – what that year away taught me to do is just to be able to slow down a little bit and take everything in so I really want to be able to go into the Olympics and take in everything I can of what's going on around me and how I'm swimming and how the other athletes are doing. While this will be my fourth Olympics and I think there might have been maybe three or four races that I've actually watched at the Olympics because you're so focused in on what you're doing and your goals so as exciting as that goal would be to achieve it is a hard goal and I'm just going to – it is in the back of my mind but I mean to just not really think about it too much to keep the pressure off.

Jeff Commings: I think that's a good way of looking at it. Now you'll be representing Zimbabwe at the Olympics, as you said it's your fourth Olympics, and I learned that you'll be carrying the flag for your country at the opening ceremonies and then I guess kind of also figuratively carrying the flag for your country, especially in the pool. What does it mean for you to be such a big sports idol for your country?

Kirsty Coventry: I'm very blessed that I've had the support from the Zimbabwe community. I don't think a lot of athletes get to experience the same kind of love and kind of following that I've received from the Zimbabweans. They've treated me well, they've been so supportive over the last 12 years and it's just such an honour for me to be able to be the flag bearer at the opening ceremony. In the past I haven't been able to do it because I've always swam the 400IM on the first day and now that I'm not swimming that race it just made it very appropriate to be able to represent my country in that way and carry the flag. It's going to be pretty awesome.

Jeff Commings: Well it's kind of sad you're not doing the 400IM. I think we were all looking forward to that rematch with you and Stephanie Rice.

Kirsty Coventry: Yes, I'm a little bit sad too. It was in the cards and then I dislocated my kneecap end of March and it just took too long to kind of come back to full working mode in terms of the breaststroke and then in early May I got pneumonia and that was kind of the stamp of approval that I'm going to withdraw from that race. It's such a tough race and I do love racing the IMs and I would have loved to have gone back up there and try to be competitive but just with the things that have happened over the last four months and training that's required for that particular race it was time to kind of bow out of it. It will be fun to watch though.

Jeff Commings: Are you just sticking with the backstrokes then?

Kirsty Coventry: Yes, I'm going to do the 100 back and the 200 back and the 200 IM so I'll be doing the 200IM, but the 400IM, just what it takes to train for that race and do well unfortunately with the things that have happened I didn't feel comfortable doing that and I want to know that I'm going into the Olympics and I can give it my best and walk away happy with that.

Jeff Commings: Yes, that's very understandable. Going to back to representing Zimbabwe, after you won your medals in Beijing was there any kind of boost in the interest in swimming in Zimbabwe after the Olympics?

Kirsty Coventry: Yes, definitely. There's been a boost in swimming probably since 2004. It's really exciting when I go home and my mom teaches little kids how to swim from ages of four up to 12, 13 years old and she's just fully booked and we've got a bunch of swimming clubs and their youngsters have really had this huge kind of boost of people wanting to just to learn how to swim and then they've gotten more interested and they've joined clubs and so it's really exciting. We've got a little bit of a dip in our seniors at the moment, we're not very strong with our seniors and people that would be kind of following my footsteps I guess where – what's the word – we're just not very strong in that area but our juniors are really strong at the moment and that's very positive for our future especially in the swimming world.

Jeff Commings: Well that's really good to hear. Kirsty, thank you so much for joining us, we're really looking forward to seeing you back in the Olympics and best of luck to you not just with training but when you step up in London.

Kirsty Coventry: Cool. Thank you very much.

Jeff Commings: All right, it's our pleasure. Thanks Kirsty.

Kirsty Coventry: Bye.

Kirsty Coventry (ZIM)

Honor Swimmer (2023)

https://ishof.org/honoree/kirsty-coventry/

The information on this page was written in the year of her induction.

FOR THE RECORD: 2008 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (200m backstroke), silver (100m backstroke, 200 I.M., 400 I.M.); 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (200m backstroke), silver (100m backstroke), bronze (200 I.M.); SIX WORLD RECORDS; 2009 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (LC) gold (200m backstroke), silver (400 I.M.); 2007 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: silver (200m backstroke, 200 I.M.); 2005 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (100m, 200m backstroke), silver (200 I.M., 400 I.M.); 2008 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (SC): gold (100m 200m backstroke, 200 I.M., 400 I.M.), bronze (100 I.M.); 2002 COMMONWEALTH GAMES: gold (200 I.M.).

The United States. Australia. Hungary. They are nations familiar to the podium at major international competitions, including the Olympic Games. Zimbabwe doesn’t fit the mold, but Kirsty Coventry single handedly put the African country on the swimming map, thanks to her consistency, longevity, and versatility.

Coventry first competed at the Olympics as a teenager at the 2000 Games in Sydney. Although she failed to advance to any finals, the experience was valuable and allowed the Zimbabwean to get an up-close view of elite racing. Over the next few years, Coventry continued to hone her skills, with a major decision to attend Auburn University, an NCAA power program.

Behind her work at Auburn, Coventry elevated her status on the international stage and made her second Olympics, in 2004 in Athens, a successful appearance. Coventry collected a full set of medals in that Olympiad, claiming a gold medal in the 200-meter backstroke, a silver medal in the 100 backstroke and a bronze medal in the 200 individual medley.

Coventry was even more impressive at the next year’s World Championships in Montreal, where she became one of the few athletes in history to win four individual medals at a single Worlds. In addition to winning titles in the 100 backstroke and 200 backstroke, Coventry was the silver medalist in the 200 individual medley and 400 I.M. Her win in the 100-meter backstroke arrived over world record holder Natalie Coughlin, one of the few defeats the American endured between back-to-back Olympic crowns in 2004 and 2008.

Lauded as a hero in her homeland, Coventry proved that even athletes from smaller nations can reach the pinnacle of their sport. She added two medals at the 2007 World Championships and in early 2008, she set her first world record, breaking a 16-year-old standard in the 200 backstroke.

At the 2008 Olympic Games, Coventry won four medals. In her first three events in Beijing, Coventry earned silver medals in the 400 individual medley, 100 backstroke and 200 individual medley. She broke through in her fourth event, winning gold in the 200 backstroke in world record time.

A year later, Coventry won a silver medal at the World Championships in the 400 I.M. and secured another world title in the 200 backstroke, where she lowered her world record. Coventry also competed at the 2012 and 2016 Olympic Games, bringing her total number of Olympic appearances to five.

Overall, she won seven Olympic medals and eight medals at the World Championships, all from individual events, and was a five-time world-record setter.

Beyond her success in the pool, Coventry has had an impact in several organizational roles. Coventry has been a member of the International Olympic Committee for more than a decade, helping to ensure positive experiences for athletes. She has also served in roles with World Aquatics and the World Anti-Doping Agency.

Kirsty Coventry will be remembered for her multi-event talent and enduring legacy as a major factor in international competition. But she’ll also be remembered as an inspiration, proving that greatness comes from all places.

Coach Kim Brackin

Auburn swimming legend Kirsty Coventry's team talk: 'Keep pushing our program forward'

AUBURN, Ala. – In a whirlwind weekend that included speaking twice at Auburn University's Spring 2024 Commencement ceremonies, two-time Olympic gold medalist Kirsty Coventry visited with the Auburn swimming & diving team after practice.

Remembering how she felt 20 years earlier as a hungry and tired Auburn swimmer when alums would speak to the team, Coventry promised to be brief.

"You've been doing really well," she said, noting the second-place finish for the men's team at the 2024 SEC Championships and a fourth-place finish and the most points since 2006 for Auburn's women. "It's nice to see your team getting stronger and stronger."

Auburn's most decorated Olympian, the seven-time medalist helped the Tigers win NCAA championships in 2003 and 2004. After winning gold, silver and bronze medals in Athens, Greece, in 2004, the Zimbabwe native returned to the Plains and won three individual NCAA titles in 2005 while earning SEC Female Athlete of the Year honors.

"I'd never been to the States before," Coventry recalled. "I'd never swum with a team before. We were on a mission to prove ourselves, get better and make each other better, and our coaches allowed for us to do that."

Then-Auburn head coach David Marsh and assistant coach Kim Brackin informed Coventry that, because of a surplus of backstrokers, the team needed her to compete in the 400 individual medley instead of the 100 back at the 2003 NCAA Championship.

Unaccustomed to swimming the longer medley distance, Coventry initially resisted.

"I only realized after the meet that the team, and what the team was trying to achieve, was so much more important than my individual goals," she said. "That's a life lesson I've taken with me that I never would have learned anywhere else other than here because I never had the opportunity of being on a team and making a sacrifice for people I loved and admired."

Not only did Coventry's willingness to swim the 400 IM help the Tigers win the NCAA title, it also paid dividends for Kirsty's career.

"The 400 IM became one of my best events. I won a gold medal in it," said Coventry, making her point to an attentive audience. "I'm grateful for them pushing me out of my comfort zone."

Coventry carried that lesson after her swimming career, serving as Zimbabwe's Minister of Sports, Arts and Recreation, as well as being a member of the International Olympic Committee.

"Those things you are learning now, you might not realize it, but those are things I've been able to fall back on," she said.

A five-time Olympian, Coventry retired after competing in the 2016 Rio Olympics, encouraging Auburn's student-athletes to conclude their swimming careers on their own terms.

"I left the sport loving it," she said. "That, to me, was super important."

After Coventry's 10-minute talk to Auburn's swim team, the Tigers asked questions for another 10 minutes, eager to learn from someone who trained in the same pool before and after reaching their sport's pinnacle.

"Everything's scary. Embrace that. You have to fail," said Coventry, foreshadowing the commencement addresses she would deliver the next two days. "I've learned the best lessons by failing, and I have failed at many things. Life has a really good way of humbling you, but what you've learned here and what you've gone through the past four or five years will help guide you.

"I hope you take the time to be grateful for where you are. It goes so quickly. Life is way more complicated once you leave this space but it's also super wonderful and exciting. Keep pushing our program forward and supporting each other."

'I left the sport loving it'

KIRSTY COVENTRY: AN UNLIKELY HERO

By Craig Lord

Kirsty Coventry was named Swimming World Magazine's female African Swimmer of the Year for her stellar swimming accomplishments in 2005. Check out the December issue of Swimming World Magazine for photos and to see what she did during the year.

Following is a story about Kirsty that offers some interesting perspective about Coventry after she did so well at the Olympics in 2004 and as she prepared for her swimming in 2005.

Of all those elevated to the status of national hero by their exploits and achievements at the Athens Olympic Games, there’s one who should get the gold medal for being the most unlikely: Kirsty Coventry.

As David Marsh, head coach at Auburn University (where Coventry graduated last spring), puts it: "The truly exciting thing that's happened with Kirsty's experience is that it has completely transcended sports and the Olympics."

Within a week of her winning Olympic gold (200 back, 2:09.19), silver (100 back) and bronze (200 IM) and becoming Zimbabwe’s first-ever swimming gold medalist, the 20-year-old white African's fame had spread well beyond the Athens pool and the Auburn, Ala. campus, where she majored in hotel and restaurant management and minored in business. Her name was even being heralded in the maternity wards of far-flung hospitals across her native Zimbabwe, where the majority black population took her success not only to heart but to the registry of births.

Kirsty Coventry Mapurisa and Kirstee Coventree Kavamba were among the first two babies to have the honourable name bestowed on them, but their parents must surely have regretted their lack of originality in the days that followed. Try these out: Three medals Chinotimba, Swimming pool Nhanga, Freestyle Zuze, Breaststroke Musendame, Butterfly Masocha,

Backstroke Banda, Gold medal Zulu, Goldwinner Mambo, Gold Silver Bronze Ndlovu and, last but not least, little Individual Medley Mbofana. The start list at swim meets in her African hometown of Harare come the year 2020 could be very confusing, indeed!

Greater the pity, then, that the national pool in that capital city--built in a high-density housing area for the 1995 All-Africa Games--is, as one Harare newspaper painted it, now merely "a green festering body of water." Perhaps that is to be expected in a nation where unemployment runs at 70 percent, annual inflation at 300 percent (if you trust government figures) or 750 percent (if you don't), where the average wage is 19 cents an hour and life expectancy is, at 38, just about as low as it was when the pyramids were built.

It would be easy to blame such poverty--and certainly the dereliction of a pool--on the economic conditions that prevail in much of Africa--where water, if you can get it, is for drinking, not swimming.

But the truth lies elsewhere: Zimbabwe is a resource-rich nation torn apart by a racist, thuggish, corrupt leadership that has squandered its wealth, let crops rot in fields for the sake of perverse ideology and encouraged blacks to harass, torture, rape and even kill their white neighbours.

When Coventry’s accomplishments sent the Zimbabwean colours up the flagpole three times in Athens--a feat not witnessed by Aeneas Chigwedere, Zimbabwe’s Minister of Sport, who is banned from traveling in Europe as part of sanctions against the corrupt regime--Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe's president, must surely have writhed as Hitler did when he watched the great Jesse Owens reign supreme over his superior race in Berlin in 1936. Yet, propaganda being the peg on which all brutal despots hang their bloody robes, it came as no surprise to see Mugabe pin his colours to Coventry's mast. Her achievements, he said at her homecoming parade and State House reception, represented "efforts underlining some degree of discipline, efforts that produce some habits." If the words were rather underwhelming, Coventry's rewards were not: U.S. $50,000 in "pocket money" (his words) and a diplomatic passport for life.

A measure, perhaps, of how much he appreciated the contribution made to Zimbabwe by a minority population? Or maybe the brilliance of her shiny medals had blinded him to the fact that she was white? After all, this was the same president who, at the height of the white farm invasions, when violence against whites was rampant, urged black Zimbabweans to "instil fear into the hearts of all whites."

Perhaps he wrote a sub-clause to his creed: Kirsty Coventry, Zimbabwe's all-time greatest athlete and the best African individual female Olympian at a single Olympic Games ever, is to be exempt.

It is amidst this background that Coventry is an unlikely hero: “unlikely”--because of the circumstances; “hero”--not only for what she achieved in the water but the gracious way in which she repaid the compliment bestowed on her by the many thousands of black Zimbabweans who turned out to welcome home their countrywoman.

"Zimbabwe Is My Home"

It would be easy to view Coventry, like so many Olympic swimmers, as a U.S. collegian with a tenuous ancestral tie to an obscure country that gets them a certain ticket to the biggest sporting show on earth once every four years. Coventry is not one of those. "Zimbabwe is my home," she says. "It's where I was born. It's my culture. I will always represent Zimbabwe. Colour doesn't matter to me."

However, it has mattered a great deal to everyone else in Zimbabwe these past years. Formerly Rhodesia, Zimbabwe gained independence from white minority rule in 1980 and soon became known as the "breadbasket of Africa," a political and economic model of black majority rule.

Mugabe changed all of that in 2001 when he ordered white-owned farms to be "repatriated." Government-backed groups invaded the countryside and forcibly removed thousands of white farmers from their land without compensation and, sometimes, with loss of life.

The white population has since diminished from 300,000 to about 30,000 of a total of 12.6 million. Coventry's parents, who own a chemicals business in the Newlands suburb of Harare, were among those who remained. So, too, did some members of her extended family who worked on the land.

"I have had very close family members and friends on farms who have gone through very hard times," Coventry told the Western media, understandably refusing to be drawn into any statements that might put her relatives in danger. "We have a large extended family, and we all have been very supportive of each other." Her family was there to greet her on a national day of celebration when she made an unplanned four-day visit home on her way back to Auburn in late August.

Coventry, who had a tattoo of the Olympic rings placed on her right hip after making the semifinal of the 100-meter backstroke as a 16-year-old in Sydney 2000, comes from a family of swimmers. Her grandfather was a chairman of the swimming board, while her parents, Rob and Lynn, were also avid swimmers.

They were not alone as Coventry stepped off the plane. "Then it really hit me," she said, recalling the many thousands of Zimbabweans--black Zimbabweans--who came to cheer her. There were traditional dancers, tribal drummers, a presidential motorcade, banners welcoming "Our Princess of Sport" and cries in Shona (the country's primary indigenous language) that Coventry could not comprehend. When she asked one of the national team coaches to translate, he said, "Give her a farm." The irony would not have been lost on any of the 270,000 white Zimbabweans who no longer live at home.

Back at Auburn after Athens, she did not quite regain the anonymity she preferred, though she was fast to recognize the value of her Olympic medals. "It's really nice," Coventry told the campus newspaper. "There's been a couple of occasions where people have been like, 'Are you that swimmer?' Teachers have been bribing me, saying, 'The only way we'll let you out of work is if you show us your medals,' so I've been taking them along with me."

For all too obvious reasons, Coventry and her family will, perhaps, never talk freely about the situation in Zimbabwe and whether the swimmer feels like the political pawn Mugabe intends her to be.

No one who has ever had to live in a country where freedom of thought is punishable by the long hand of the law or by the sharp fist of the thug, would dream of criticizing diplomatic responses such as that graciously delivered by Coventry at her homecoming parade: "I think every country goes through bad years and good years. I hope this (her success) gives Zimbabwe hope, and that they can take something good out of it. All sportsmen and women can take inspiration from it and know that they, too, can follow their dreams."

A Light in the Darkness

For sentiments so often unspoken by the shrinking white minority, we must, then, turn to the media who have observed events at close quarters. Pius Wakatama, a reporter for All Africa, described Coventry as "a Light in the Darkness of a pariah among democratic and civilized countries of the world" in an article summing up the swimmer's splendid achievements in Athens.

Wakatama had been present when Coventry first became the toast of Zimbabwe back in 2002, when she won her country's only gold medal (200 IM) at the 2002 Commonwealth Games in Manchester, England. At the time, pressed on the situation in Zimbabwe, she referred to her parents and sister who live in Harare and said that "the things they were going through were hard."

Wakatama wrote: "We all know what she was talking about. She was talking about the hell that her parents and most whites are going through today whether they are citizens or not. We all know that she was talking about the racial insults, threats, extortion, rape, torture and murders that the white Zimbabwean community and those blacks labelled 'British supporters' are going through at the hands of the government."

But a nation's true borders lie around the human heart, and Coventry is a patriotic Zimbabwean. "I am ecstatic," she said in Manchester in 2002, a message she repeated in Athens, adding, "Hearing the national anthem from the podium made me feel so proud to be a Zimbabwean," Wakatama notes that not everyone feels the same: some of Zimbabwe's top sportsmen, such as Henry Olonga, Heath Streak and most top white cricketers have left their country in disgust. In addition, Edgar Rogers, former secretary-general of the Zimbabwe Olympic Committee and outgoing Commonwealth Games Federation vice president for Africa, renounced his Zimbabwean citizenship and announced his departure to South Africa.

Wakatama laments their decisions before concluding his article with some of the wisest words to have been written on the Zimbabwean crisis: "As I watched the enthusiasm with which Zimbabweans welcomed and congratulated Coventry and how they took her glory as their own, I again concluded that black Zimbabweans are not hate-filled racists at heart. If that is the case, why is it that our government media propagate racial hatred and negatively stereotype whites as part of their political propaganda?

"Don't get me wrong. I am not and will never be an apologist for white racism. I am more aware now than I was during some of the evils of colonialism and the racial discrimination of the past. I was a victim of that myself. However, I am intelligent enough to realize that living in the past will not get us anywhere. I will not replace white racism with black racism. I believe that this is the attitude of the majority of black Zimbabweans. The hate-filled racist propaganda we are daily bombarded with through the media comes from idiotic politicians who are good for nothing. They blame the few whites left in the country for all the evils besetting Zimbabwe today. History, therefore, becomes very convenient to them."

Coventry may one day feel free to express her own views on the subject. For now, she savours that special day when colour faded into the background and a homecoming queen's parade was broadcast live on national television for two hours.

"It was very, very overwhelming," Coventry said. "I felt so much pride, seeing how much it meant to so many people. It really brought tears to my eyes. There were no political issues. There were no racial issues. Everything was put aside for a few days so people could celebrate. It was so nice to meet so many people all happy for the same reason. Hopefully, it will carry on like that."

In showing such spirit, said one African publication, Coventry had helped to soothe Zimbabwe's soul. For that reason, if no other, the swimming world should wish more success for Coventry as she pursues her next Olympic dream.

Craig Lord, a writer for The London Times, is Swimming World Magazine’s European correspondent from Great Britain.

KIRSTY COVENTRY AT A GLANCE:

Name: Kirsty Coventry

Date of Birth: Sept. 16, 1983

Birthplace: Harare, Zimbabwe, Africa

Height: 5-8

Weight: 132 pounds

Parents: Rob and Lynn

Favorite Music: “I enjoy all.”

Favorite Food: Chocolate--“I have a really bad ‘sweet tooth.’”

Favorite Book: “Drum Beat”

Secret Plan in Life: “I want to open my own restaurant.”

KIRSTY COVENTRY: An Inspiration for a Nation

By Wayne Goldsmith

Kirsty Coventry, who competed in her first Olympics in 2000 at Sydney, will be representing Zimbabwe in Rio de Janeiro for her fifth straight Olympic Games. Now 32, Coventry recently reflected on her remarkable swimming journey that has resulted in her be- ing tied with Hungary's Kristina Egerszegi for the most individual Olympic medals won by a female athlete.

In the mid-1990s, my then fiancee (now wife), Helen Morris, and I were in Harare in Zimbabwe conducting a FINA coaching clinic. As part of the clinic, we had the opportunity to work with Zimbabwe-based swimmers and coaches in the classroom, on the deck and in the pool.

We met some wonderful people during that tour, but one person really stood out: a tall, skinny, blond-haired girl named Kirsty Coventry. Even as a young age grouper, she stood out as talented and tenacious in the water, a hard worker, but always smiling, pleasant and respectful. She was already showing many of the characteristics that would take her to the top of world swimming.

Helen and I followed her career with great interest and always enjoyed seeing her race internationally, knowing what challenges and difficulties she had overcome along her swimming journey. Recently, I had the pleasure of watching her compete at the Arena Pro Swim Series in Mesa, Ariz. Seeing her race again prompted me to contact her and ask her to share just some of her remarkable journey from the old swimming pool in Harare to Olympic glory and beyond.

Q. WAYNE GOLDSMITH: Kirsty, thank you for your time and energy. Tell me a little about your early life in Zimbabwe. How did you become interested in swimming, who were your coaching in fluences and what were your early memories of training and competing?

A. KIRSTY COVENTRY: Growing up in Zimbabwe was amazing. Zimbabwean people are very warm, humble and accommodating.

There was an anthropologist doing a study somewhere in Africa, where he placed a bowl of fruit underneath a tree and told some children across the field that whoever got to the fruit first could have it all.

An amazing thing happened- they all held hands and ran to the fruit together!

When asked why they did that-i.e., when one of them could have enjoyed all the fruit-they responded, "Ubuntu. How can one of us truly enjoy the fruits if we cannot share it?"

This is what it was like growing up in Zimbabwe. We were very fortunate to have a pool at our house, and my parents often laugh about how I would instinctively head toward the pool from a young age-similar to a newly hatched turtle.

My mum taught me to swim. I was swimming from the age of 18 months... and that was it!

Other children were coerced into finishing their homework and chores with chocolate and TV. My parents used swimming!

I would caution any parent who doesn't allow his or her children to have fun in the pool because even when I joined my first swim club aged 6 years old, it wasn't about competition or being serious-it was about finding a group of kids that I could have fun with.

It was my natural competitiveness and the opportunity I had to swim that led me to club swimming.

This, in turn, taught me about winning and losing. I hated to lose, so this meant I had to train harder! I was never a bad loser, and I have my parents to thank for this.

I remember one instance at a competition when I was up against a slightly older girl. I would win, and she would literally have a tantrum. She would win, then puff out her chest and parade around the pool.

My parents pulled me aside immediately after the meet and told me that if I ever behaved like that - and it didn't matter how old I was - they would not let me swim again! I felt like it was my fault she behaved like that, so I made sure not to hang around her again.

My parents were my greatest influencers and taught me to win with humility and to lose with grace. They taught me what was good and what was bad. Nothing was complicated- it was right or wrong...simple.

Being humble has always been my personality, and it is probably a combination of good parents and having to work hard for everything that I have managed to achieve so many of my goals. Nothing was ever given to me.

My coach, Charles Mathieson, wasn't any different to my parents. We were taught to behave properly because if we didn't, there would be consequences to our actions. This made us accountable to each other and to ourselves.

My parents were also very good at leaving the coaching to the coach, and if I needed parenting, my coach would send me to my parents. There was a distinct line between the two roles.

Talk about coaching discipline! My swim coach growing up was a butcher. He would leave home at 4:30 a.m. to come and coach us, drive to work afterwards and meet us back at the pool at 5 p.m.

He now lives in Phoenix, Ariz., looking after swimming pools, and he still leaves home at 4:30 in the morning.

Until I started going on tours to South Africa and Europe, I had no idea how bad our swimming facilities in Zimbabwe were. Then, when I saw what "real" swimming pools looked like, I trained harder. Instead of whining about our facilities, I did what I could to earn the opportunity to swim in those amazing pools again - it was my reward for training harder.

I have learned to focus on solutions, not on problems, and that is not just from playing sport, but because of where I come from.

Many people may think of it as a negative, but it's only a negative if you don't succeed.

If you do make it through all these obstacles, you have the ability to be the best in the world because everything you have endured has made you so much stronger-not just physically, but mentally and spiritually.

There is something dreadful, but at the same time, thrilling, about jumping into a cold pool at 5 a.m. for morning training - we do not have heated or indoor facilities in Zimbabwe! When it gets too cold (about four months of the year), swimming is over, and we go and play other sports. You don't whine about not being able to swim- you get on with it and do what you can.

Often we would have to check the pool for frogs and frog eggs because there is nothing worse than being in the middle of a stroke and feeling the slimy roughness of something gross!

WG: Was there a time or a moment when you “fell in love” with swimming and decided to see how far you could go with it?

KC: When I was about 8 or 9 years old, I told my parents I wanted to go to the Olympics and win gold.

Thinking about it now, I don't know if I even knew what the Olympics was about. My parents are huge sports fans, and my uncles swam and boxed for Rhodesia...so maybe I knew a little bit about it.

Was this the turning point in my career? I don't know. I have always been goal-oriented, even though I may not have known what a goal was when I was young.

My parents never put me in a swimming club - I wanted to join. I did when I was 6.

My parents never told me that I should think about the Olympics. I told them I wanted to go. I did when I was 16.

I would go fishing with my dad on Lake Kariba or the Zambezi River, watching elephants bathe while reading a book or while fishing; listening to the lions roar while cooking dinner; laughing at the baboons chasing each other; amazed because the giraffes were as tall as the trees!

I was always so excited to catch a fish, but I always knew I could catch a bigger one. It wasn't about being unhappy with the fish I had just caught-it was an inner feeling that I had to keep fishing and try to catch a bigger one.

I think that inner feeling was belief. I didn't need my dad to tell me that. I knew if I kept trying, I would get it.

I don't think there was a specific moment when I decided to see how far I could go. I think it was a progression of desire fueled by a combination of the influence of having good people around me, the opportunities I took, my own determination and self-belief.

WG: It can be tough being a swimmer in many parts of Africa— lots of challenges with facilities, access to world-class competition and many other tough struggles with adversity. How did you overcome these challenges and remain focused on becoming one of the best female swimmers in the world of all time?

KC: I at least had the opportunity to learn to swim. Many people in Africa didn't, and still don't. I think I was able to see this every day, and I've always appreciated how fortunate I was.

For a long time, in a way, I could have been seen as the "privileged white kid" because swimming was seen as a white person's sport. Compared to the majority of the people in the country, I guess we were privileged, but we certainly were not driving flashy cars or flying off on holidays anywhere.

From an early age, I knew how lucky I was. It was only recently that I truly appreciated just what my parents had done for me.

We never had enough money for tours (e.g., travelling from Zimbabwe to South Africa for competition), so my parents would sell hamburgers and hot dogs at the swimming meets and outside the supermarkets. My memories of these times are running around, chasing my sister with an ice cream in our hands, and wearing the biggest smiles and sharing the deepest laughter.

We were such happy children because my parents never made their problems our problems. Similar to the wildebeest on the African plains, only the fittest survive. If we constantly had to worry about problems, we would never do anything. We were forced to be innovative, make a plan, come up with solutions and get on with it - that's what makes you a survivor.

Despite all the challenges you face - and I'm talking about real-life difficulties - if you can maintain your path and reach your goals, you will be more than successful.

I believe it's important to strive to be more than just successful in athletic terms - it's about accomplishing your own goals with humility while helping others to reach their goals.

WG: You’ve had the experience of working with some outstanding athletes and coaches...and now, you’re training with Coach Dave Marsh at SwimMAC in North Carolina. What qualities, values and character traits do you feel are essential for swimming success?

KC: While it's not the most obvious character trait to have, one of the most important in my view is the capacity to be self-aware.

Swimming is a lonely sport. You have a great team around you, but when you are doing the volume and the hard sets, you have to realize that your team is only there to push you and support you. You have to do the work, and you can be stuck in your thoughts.

My husband, Tyrone, knows not to argue with me before a swim practice or to try and discuss anything too serious just before training. He will have forgotten about it by the time I get out, but I would get out seething or overthinking - not what a swimmer needs!

Self-awareness is about knowing who you are as an individual, separate from your environment and other individuals. If you are self-aware, you can be honest with yourself. If you are honest with yourself, then you can start being honest with your teammates, your coach and your support network-e.g., parents, friends, spouses.

This helps you with your goal-setting because it makes you accountable to yourself. This, in turn, creates an easier job for your coach because now, he or she can focus on coaching you and not having to "mommy" you.

To be successful in anything, you have to be passionate, purpose-driven and disciplined.

Passion is your desire to do something, but passion is the easy part.

Without a clear purpose, you will find it difficult to stick to the program, and it makes being disciplined much harder.

Discipline is about making sacrifices to ensure you reach your goals. Your goals might change, so you have to be able to adapt.

The purpose is deeper than your goal. As a younger athlete, I only had goals, but now as a mature athlete-and by "mature," I mean mature in emotional intelligence and spiritual growth - I have a greater purpose than just winning gold medals and breaking records.

As important as it is for swimmers to have these characteristics and traits, it is vital that coaches also share some common values with their athletes.

The bond between coach and athlete can then, in turn, become greater, and this will develop more accountability, respect and trust.

I have been fortunate to have coaches such as Kim Brackin, David Marsh and Bob Groseth, whose values reflect many of my own - and we've all worked together well as a result.

WG: You’re an inspiration to many young athletes in Zimbabwe, throughout Africa and in many other parts of the world. If you had one piece of advice for a young kid—swimming in a pool in Africa and with a dream of following you on the path to Olympic glory — what would it be?

KC: We cannot predict when an opportunity will present itself, but we can strive for those opportunities so that when they do come, we must be ready.

If you choose to give up because of the things that are outside of your control, then you will have definite failure. However, if you can hold on and stay determined-if you never give up-you will always have the possibility of success.

This is stronger than hope - this is your will, and no one can take that away from you! -<

https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/22-kirsty-coventry-feature.pdf