The 1956 Olympic Games

by Sue Roberts

I wrote this story shortly after the games for my dad’s company magazine. They were printed in three issues of the mag in 1957. They are very personal and I don’t think of much interest to anyone else – especially as I couldn’t be too outspoken – The pics are probably not usable – and I didn’t get those originals back. I think Dee has sent you a better one of the four of us with our so-called coach Alec Bulley. He lived in Durban. We four girls – and 3 of the 4 men - were all coached by Cecil Colwin (subsequently Canadian National Coach) – but he was a newcomer on the scene. They were poles apart in their training methods ….. Looking through this again reminds me how little we knew about the Olympics then – no TV in SA and just a few newspaper reports – possibly something on African Mirror a news programme that used to run at the movies before the main feature. So it was a huge adventure for us all.

Many people have asked me whether our short six-week trip to the Olympic Games in Melbourne was worth all the hard work we had to do first. My answer has always been an emphatic "Yes".

We started working for the games six months before we actually had to swim our events there. At times is was just a long heartbreaking grind, but the fact that we trained together lightened our task considerably. I think we swimmers were the most fortunate. Our coach had the training of the team entirely in his hands and we moulded into a uniformity of ideas and could help each other when we were on our own in Melbourne.

The first reward for our work was the arrival of a very special letter. We were congratulated by the Olympic Assoication on our selection to represent South Africa at the Olympic Games. From then on there were regulated notices from the council informing us of their latest plans.

The complete team of 51 athletes and officials, only 6 of whom were girls, was assembled at the police training camp in Voortrekker Hoogte. Here we thoroughly enjoyed two weeks of intensive training in bright sunny weather. There was a wonderful spirit of co-operation and we all felt we were working together for the same ideal. Here we met other members of the tea, of whom we had only read in awe in the newspapers. I can remember hardly daring to breathe when Jan Barnard first talked to me. I can now treat him as an old friend.

Fortunately for us, the very strict discipline of the camp did not apply to us. Otherwise, we would have had to run everywhere. It always used to amuse us to watch the trainees scampering across the grounds every time a bell rang. They were not allowed to walk anywhere - they must either march or run or woe betide the lazy one who sauntered to his class.

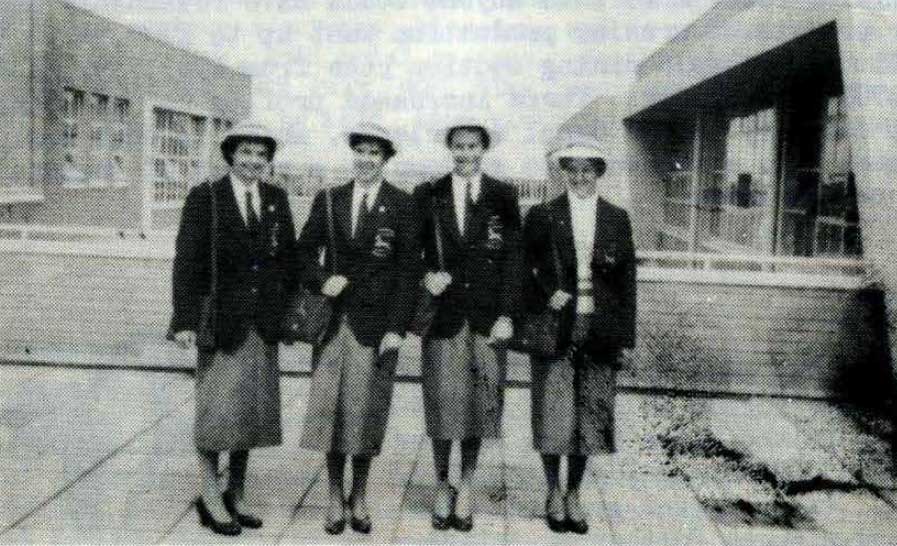

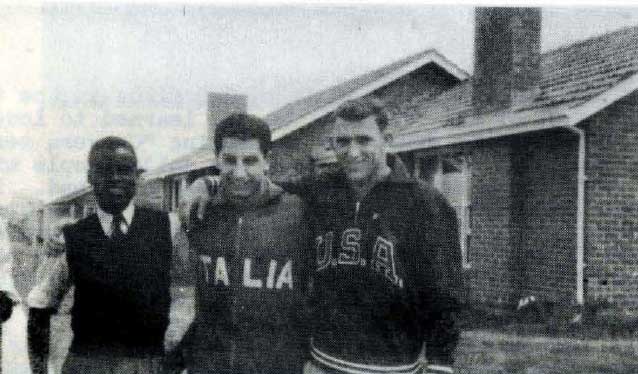

The author Sue Roberts, with Toy and Jeanette Myburg and Moira Abernethy in their new Springbok blazers.

Everyone was most kind to us and helped a great deal to promote the comradeship of us all. We were all presented with vitamin health foods by a number of firms and began to feel quite proud of ourselves.

However, Pretoria was just a tiny taste of what was yet to come. We all had to be measured for our uniforms, and one great day they arrived including the longed-for Springbok blazer. The first day we wore those was proud day indeed.

Taking off from Jan Smuts

On November 5th at 10 a.m., a Monday morning, our huge Qantas Constellation plane left Jan Smuts airport outward bound for 'Australia. There were a few sad farewells, but at heart, the team was raring to be off. Our first flight was only seven hours and then we had 24 hours to spend in Mauritius - a jewel of an island made the more dear to me as my parents spent their honeymoon there. Subterranean disturbances millions of years ago caused this little lump of land to be pushed up above the sea. A huge volcano erupted and spilled its lava about it to make a great heap of fertile volcanic soil. The Mauritians cultivate a fine species of sugar cane which is almost the only wealth of the country. The people themselves are very poor. Taxation is very heavy. A man has to pay almost 70%. of his wages in taxes. Thus we find that the people don't work very hard, as it is just not worth it. The inhabitants are mostly of Indian origin, but while French are the chief landowners, English is the official language, but 90% of the people speak French. We toured the island and swam at one of its most popular beaches. The water is clear blue and very warm and calm as it is protected by a coral reef from the breakers of the Indian Ocean.

We left Mauritius for the Cocos Islands at six in the evening. We were very heavily loaded, as we had to carry enough petrol for four hours of emergency flying time. The islands are so small that the pilot has to use the stars as well as a compass and a radio to find his way. The flight from Mauritius to Cocos is the longest oversea trip in the world today. It takes 11 hours. From the air the islands look like a tiny black and white imperfections on the smoothness of the sea. There is only one island long enough to have a runway. There are 30 islands altogether, set in a three-quarter circle around a brilliantly clear aquamarine lagoon.

The airstrip at Cocos Island

Only the main island is inhabited and only the Qantas employees and men who work at the weather station live there - and they love it. The other islands a little tufts of rock and course vegetation sticking out of the water. It is like a dream of paradise here. The great blue rollers break upon the reef and flow gently into the clear blue-green lagoon. The beach, fringed by feathery coconut palms, stretches as far as one can see, dazzling the eyes with its whiteness. It was very hot, yet we could not swim as the coral became poisonous in hot weather and this was definitely not the time for blood poisoning. So we satisfied ourselves with a cold shower and plenty of coconut milk to drink.

I don't remember much about Darwin, except that it was like stepping into a steam-bath. The monsoon was just about to break and the heat was terrific. We arrived at midnight and left an hour later on the last stage of our trip to Melbourne.

Our arrival in Melbourne was not exactly comfortable for everyone. The pilot circled the plane low over the city and we had an excellent view of the stadiums and the village., but nearly everyone was sick. What struck me most about this city is its extent and its huge parks. Melbourne has a population of 1 1/2 million, and even from 3000 feet in the air, their houses stretched as far as the eye could see.

We were met by an official of the organizing committee at the airport. A hanger had been converted into a reception hall for all Olympic visitors and it had been very attractively decorated with Olympic and National emblems. Two busses, bearing the sign "Olympic Special" were assigned to carry us to the village.

One of Melbourne's nice parks.

I was not very impressed by the suburbs through which we passed to reach the village. The houses are all very small and gardens almost non-existent. This is because of the acute shortage of household servants. Not once during all the time I was in Melbourne did I really see a modern-looking house or any shopping centre to compare with our fast-growing Rosebank. Apparently all constructional development ceased entirely during the war as there was no labour and it has been very slow to start again. This was one of the most striking differences between Melbourne and Johannesburg. While our shot upwards with modern skyscrapers replacing the older more dignified building almost changing the face of the city in the last decade, Melbourne has merely grown a middle-age spread. The central city has few buildings exceeding six stories. I think this and its skyline of church spire and its extensive well-kept parks give Melbourne its air of such quiet beauty.

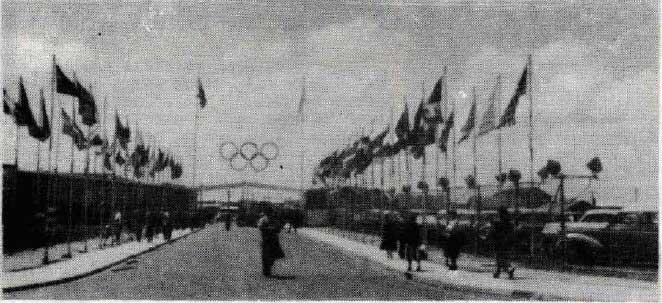

No one knew quite what we would find when we arrived at the Olympic Village. We all knew that a small suburb had been built specially to house the athletes, but none expected the modern well-equipped little city we were brought to. A long double line of the flags of the competing nations stood guard on either side of the road. At their head was a sentry box with a sturdy wooden beam barring the entrance to the village.

Only those holding special identity cards, which all athletes were meant to carry, could pass through. Round the entire village was a very high fence to keep the too-ardent fans from the objects of their worship. It was decided that the houses for the athletes would be used for permanent residences after the games and they were designed accordingly. I have never seen such a large scheme constructed on such a small scale. The whole village almost Looked like a toy one. There were little miniature houses with pastel-shaded walls, grouped prettily around open lawns. All the roads were very narrow - two cars could barely pass - and while there was so much activity many of the roads were made one-way. I think we all fell in love with our own little town. We liked the tiny little double-storied flats, the total height of which was the same as that of a normal house. Scattered about were the athletes in cheerful groups clad in a galaxy of coloured tracksuits. The Canadians wore bright red, the Brazilians emerald green and yellow, the Russians royal blue with C.C.C.P. embroidered in white letters on their chests and the Swedes in yellow with blue crowns beneath the letters SVERIGE. The French lived up to their reputation and one would have mistaken their smart blue outfits with their white yokes for ski suits, but for the large letters spelling FRANCE on their backs. The women's quarters, although part of the village, were separated from the other houses by an even higher fence.

The "Fence"

An Object of Worship

We were told that it had been specially raised to 15 ft 1/4 inches, just 1.1/4 inches higher than the world pole vault record. There was only one entrance, which was guarded day and night by sentries, while at night additional sentries patrolled the fence. Our six girls shared a house right down next to the fence and sometimes we felt rather like monkeys in the zoo as spectators stared at us through the fence or threw autograph books over, tor us to sign. We had three bedrooms, as the living room had been converted into a bedroom, a kitchen, a bathroom and a laundry, all very small. The village was entirely self-contained. We had 10 big kitchens with a dining room on either side. Each country was assigned to a dining room and some of the larger teams had one completely to themselves, while smaller teams shared with people of the same eating habits as themselves. We shared a dining room with a very mixed crowd. We had Kenyans, Nigerians and Jamaicans among the non-Europeans and Canadians and North Irish, who were all whites. We were a bit dubious as to the wisdom of such a scheme, but it turned out to be the best thing that could have happened.

We mixed quite freely with the coloureds and found them to be very well mannered and a few of them better educated than most of us. The food was wonderful. The Olympic organisers really turned up trumps there. Many of us wished our events were over at the beginning so we could really tuck in. Special 11 oz. steaks had been ordered for the athletes and I can assure you one steak makes a plateful. There were always two meats, steak, fish, curry and rice and an assortment of cold meats; as well as quantities of fruit, gallons of milk and fresh fruit drinks. We always had asparagus and smoked salmon. and sometimes mussels or oysters. If anyone did badly it wasn't for lack of food energy.

We had our own hospital with eight doctors, a shopping centre where souvenirs as well as usual commodities could be bought a special restaurant open until midnight, a post office and a dry-cleaning depot, which did free mending. There were also many stands where one could get free Coca-Cola and all sorts of hot milk drinks at any time. We used the town hall to-be as a recreation hall and every night there was some kind of entertainment there. Frankie Lane himself brought his entire show to the village and was given an overwhelming reception. Some nights we were shown films and we had radio quizzes and informal hops.

The relations between the athletes were excellent. The village had an air of happiness and general good fellowship at all times. Nearly everyone has asked, "and what were the Russians like?" It isn't a very easy question to answer, as we never got to know them. Language was a great problem and the Russians in particular kept very much to themselves. We were on smiling terms with a few of them and there was one boy who spoke English. We never touched on political subjects, but in everything else, he seemed a very nice, normal sort of person. Once returning after a very late training session the Ruskies, as we all called them, were in our bus. I was starving, so they very kindly fed me with the most enormous Russian "Dagwood". It consisted of heavy slices of the queerest looking and tasting things between two thick slabs of coarse black bread. They all watched eagerly as I struggled with it and I felt I could only avert an international crisis by forcing down every morsel of it. I hardly ate for two days afterwards. Still it showed that even Russians are taught to share what they have with others even if she isn't a communist.

It was on the buses which took us 10 miles to the training venues that we met most of our friends. We all learned to love the shy open-hearted Phillippinos who amused us by singing "Ca sera sera", the current swing hit in their home town. They are jolly people with a 'perpetual smile on their faces and ever ready to help a friend. The youngest athlete at the Games came from their number. She was a cute little girl of thirteen with long black pig-tails and slanting black eyes. She couldn't pronounce "f" and as the conversation often centred on our swimming she used to tell us her time was pipe pipteen (5.15), much to our amusement.

The Pakistanis were often our travelling companions and we came to know them well. Their country has an intense dislike for South Africans because of our colour bar and they fine South Africans who land on their airports in transit. Yet to us they were most courteous and one even offered me a comb once on the way home. This delighted our coach, Mr. Bulley who said I needed someone to bring it home to me·that I looked like a Figian, who wear their hair in a great nest above their heads. I wasn't exactly flattered.

At first we spent a lot of our time swapping badges and we made a Iot of friends this way. Each team was given national emblems in the form of brooches, pins or pennants. We all had little gilt springboks which were very popular and sometimes, when trade was good, we could get two foreign badges for our one. Autograph hunting, or rather escaping from autograph hunters, was an other occupation. At first, we were flattered and proudly signed every book put before us, but soon the children became the bane of our lives and we became thoroughly fed up with all autograph hunters. Collecting autographs on our own account was not very satisfactory, as it was difficult to pick out the leading athletes among the thousands who thronged the village.

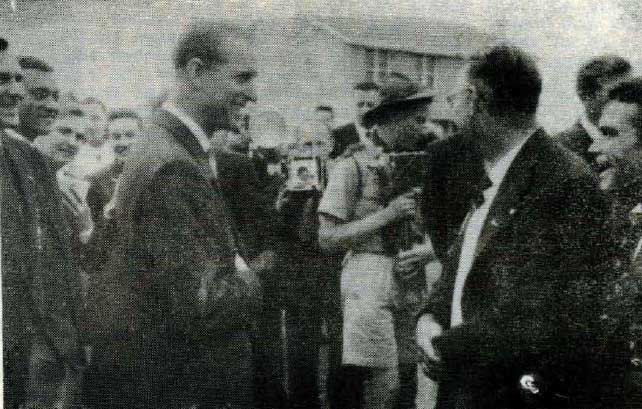

The visit of the Duke of Edinburgh was a great event indeed. His Royal Highness had been invited to an informal luncheon at the village. A few members from the Commonwealth teams were asked to come too, but we were especially honoured, as the Duke had accepted an invitation, suggested by Mr. Emery, our manager, to see over an athletic household. He spoke to a lot of us, including myself, and was most, charming and friendly. He visited the manager's home first and then, deciding that it looked too tidied and unnatural, he made his way over to the yachtsmen's house. There was a screech of consternation as the owners realised his intentions and scuttled into their back entrance to try to neaten up in the few seconds they had before the Duke entered their abode.

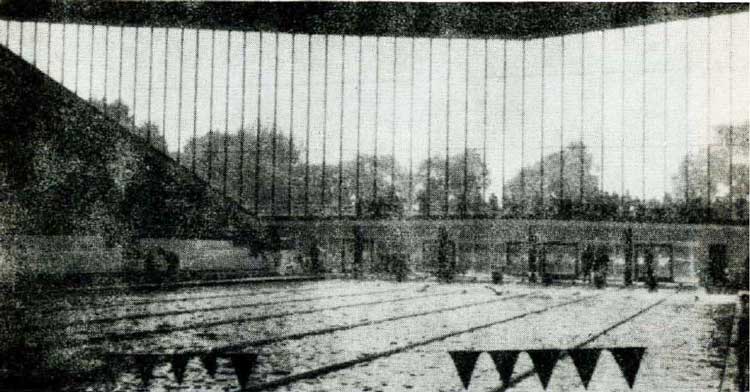

At this stage, we were training twice a day in a number of different pools. The Olympic pool is the best I have ever seen. It is indOOr!!and a marvel of modern construction. The two end walls are made entirely of glass and thus it has the advantage of being well-lit as well as va1'III and sheltered. On either side are the stands seating 5000. The water was heated and it became a real pleasure to swim in something so beautiful. There was a separate pool for the diving, with a tower carrying four firm boards and two springboards, which were in continual use.

The first two weeks we were in Melbourne slipped quickly by, and then a different atmosphere began to creep in. Faces grew more determined and many seemed worried. For the moment, the carefree days were over. We seemed to be shorter of temper now, and began to flare up at any little thing. Everyone was keyed up for a great event.

Whether it was by coincidence or careful planning the Olympic Games were scheduled to be opened on the first day of summer. Once again we had an excellent example of the magnificent optimism of the Australians. The three weeks preceding the opening were dogged by bad weather. Dill drizzly clouds rolled dismally across from the sea and wept copiously on the Olympic City. Yet, though the cold, wet weather showed no signs of abating, bright forecasts of a hot clear day for the 22nd of November appeared in every paper. The prophets assured us that the first day of summer would be perfect for the Great Ceremony and the miracle happened; we were blessed with the first day of sunshine since our arrival. It seemed that even the elements were paying tribute to the ancient festival of the Olympic Games

We had all been instructed as to what part we would play, and we had to practise marching up and down the streets of the village. Neville Price caused quite a stir among some of the foreigners. He was the flag bearer, and as there was no flag immediately available, he used an old broom. There was a roar of laughter as the South African team in full regalia stepped out solemnly behind a broomstick.

The athletes left for the stadium In a convoy of busses. There were, I think, 160 all told and all traffic was held up for the. The emotions experienced during this ride and the consequent march are indescribable. Crowds of people lined the streets and cheered each bus as it went by and waved flags and made victory signs. Even the thought of it now sends a tingle up my spine. We were treated like royalty. Before we marched into the stadium we went to an assembly ground nearby and each team got into line behind its standard. What a beautiful sight It was. A mingling of all the colours under the sun. The Indians wore aquamarine blazers with turbans of blue and gold, the men had brilliant scarlet blazers and white trousers, and the English girls were smart and cool in their white pleated frocks and red bags and shoes. But I could be all day describing everyone and would still not be done.

The Greeks, as originators of the Olympics, led the teams in. The others followed in alphabetical order with Australia as the host nation, bringing up the rear. This procession was I think, was the most wonderful experience of my life. These words are too much of a cliche nowadays for people to appreciate their real meaning. We marched through a narrow passage with people crushed five deep along the netting to see us pass and with their cheering loud In our ears we neared the great stadium. We heard the steady throbbing of the drums and like some mighty pulse it beat in our hearts. I can remember so clearly that moment we paused before the gates — the world seemed ours for the taking the people out there waiting for us. As we went in there was a cheer from those nearest the entrance and as we walked past cheer upon cheer followed us around the arena. We saluted the Duke and I felt as though I was walking on air.

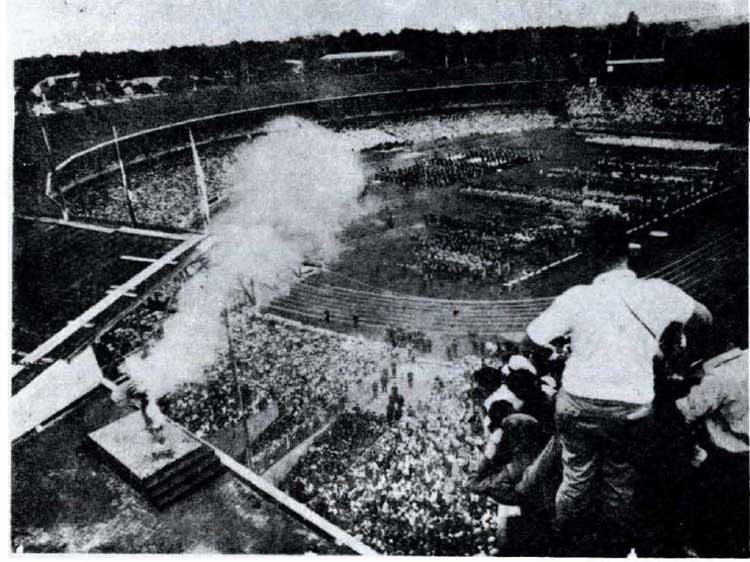

When all the teams had taken their place facing the Royal box the official opening began. After two short speeches stressing the goodwill promoted by the Games and the essential spirit being competing and not winning (which comforted us considerably) the Duke of Edinburgh declared the 16th Olympiad open. There was a gun salute, the flag was raised and 2,000 pigeons were let loose. These correspond to the carrier pigeons of ancient times which carried messages home to the villages of Greece calling for the laying down of all weapons during the days when the games were in progress. Then John Landy, the famous Australian miler, took the Olympic oath on behalf of all his fellow athletes, swearing to behave in all things as behove a true sportsman. The climax came with the arrival of the torch bearer — a young Australian — who sprinted once round the track with the flame streaming behind him and mounted the dais way above the crowd. Here he stood one moment poised with the flame held aloft and then he plunged it into the great torch. The spark so carefully tended, that once had Its place in a Grecian temple now kindled a light in a new young country. As the flame shot skywards there rose a great shout, for this symbol is the very core of the Olympic Games

The opening ceremony as the Olympic torch is plunged into the bronze bowl

The flags of the competing countries circled the stands and tier upon tier of people looked down on us. The brilliant green of the grass with the multi-coloured uniformed teams, the blue of the sky and the thousands of spectators made a bright scene indeed.

But the fun was over. The hard work must start now. We vent for a loosening up swim at 9 p.m. that night and we began to feel that perhaps we should have trained just that little bit more.

For us swimmers life vent on very much as usual as the swimming events only started in the second week we still trained twice a day and seldom found time to watch any athletics. I was fortunate enough to watch that great run of Vladimir Kuts In the 10,000 metres. Never have I seen such grit and determination so deservedly rewarded. Running like a human machine, yet with a bunch of brains and tactics in his head, he ran one of the most outstanding races of the Games. He made Pirie, a world champion, look like a beginner. True to the continental spirit he did not stop running after his 35-odd gruelling laps, but burst through the tape and ran a victory lap raising his hands above his head and waving at the crowd. The women's and men's 4 x 100 relays were also most exciting - but these are gems in a treasure trove. There was a wonderful scoreboard that worked with lights, which shoved the names of the first six competitors in each race, their country, their time and the Olympic and world record for that event. For the field events there were special little boards which were worked by hand and which revolved slowly so that all could see. The officials amused us, for they used to march on and off the track in a line like little black beetles, looking very important in their straw bashers and special blazers.

The swimming stadium

Our swimming was upon us all too quickly. The first heats vere at night and we stayed in bed with butterflies in our tummies most of the day. The actual competition was a bit of a disappointment to me personally and I think to some of the others also. There seemed to be almost a complete lack of atmosphere. The crowds watching were not as big as those who had watched practices, as no one could sit in the aisles or two to a seat. We all had to stay in the changing rooms our race and here there was an air of false gaiety. It was such a big thing to swim In the Olympic Games that we tried not to think of it. Instead, we played cards and someone played a ukelele. This was the first time, when the day came on when we had to swim our relay, we were healthily nervous and could view the prospect without shrinking.

We came first in our heat and had the second fastest time but we knew we would have to swim all out to cone third in the final. Not one other country had entered their best swimmers in the heats, but there were only four of us so no one could rest. That relay final was worth all the training we had done. I swam second and had the thrill of seeing our last swimmer touch just ahead of the German girl. We had to take part in the victory ceremony and stood proudly on the dais and watched our flag hoisted slowly up the mast. It is the custom for the national anthem of the winner to be played and the winner's flag rises on the middle mast with those of the 2nd and third place on either side. We were then each presented with a Bronze Medal. All the medals at the Games are alike. They show in relief on one side a Greek torch bearer and on the other a Greek athlete carried shoulder high by his fellow competitors with the words 16th Olympiad Melbourne, 1956.

The winner receives a gold medal, and the other two a silver and a bronze.

That same night we went to see some cycling. I had never seen cycling before and was fascinated. It is apparently a disadvantage to take the lead so at the start the two competitors stood still and the one who loses his balance first is forced to take the lead. We saw Jimmy Swift win a bronze medal in the time trial. Most unfortunately we had little chance to watch any other sports. A competitor, unless his events are early, sees and hears less about other sports than the spectators. We did not often buy a paper and could hardly ever listen to or watch events even on T V. I am determined to go to one Olympiad as a spectator, but would never change my experience as a competitor for that of a spectator.

There was a short ceremony when the games closed The teams marched into the stadium in no special order and after a few speeches the Olympic flag was lowered and the flame quenched. The president bid the athletes go home in peace and called on the youth of the world to meet again In Rome in 1960 for the 17th Olympiad. A choir sang nostalgic words to the tune of "Waltzing Matilda" as we marched out, while the crowd waved and shouted and many wept openly. It was a sad and moving ceremony conducted in a fine drizzling mist. The curtain was down on the 16th Olympald leaving behind a wealth of happy and unsurpassable memories.